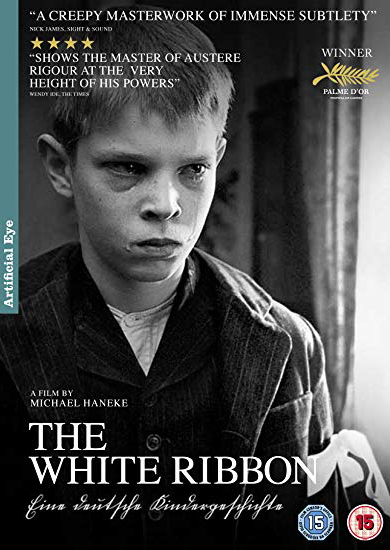

The White Ribbon

Strange events happen in a small village in the north of Germany during the years just before World War I, which seem to be ritual punishment. The abused and suppressed children of the villagers seem to be at the heart of this mystery.

Film Notes

Austrian film maker Michael Haneke uses the historical setting of pre-Great War Germany in his masterly 'The White Ribbon' winner of this year's Palme d'Or at Cannes. The neat, north German protestant village has a timeless quality that, with the absence of motor cars, gas and electricity and the reliance on horse-drawn transport, suggests a feudal community at any time in the late 19th or early 20th century. At the top of the pile is the Baron, owner of the land. Attached to his estate is a burly steward and the chief figures in the village are the stern Lutheran pastor, the Doctor and the Schoolteacher who is insecure, immature and the only unmarried one amongst them. Everyone else works on the land. The film's narrator is the schoolteacher. From his infirm voice, we infer he's looking back on events from old age. The Schoolteacher interweaves two narrative threads. One is personal, lyrical, nostalgic. The other, dominant thread is a series of apparent accidents and atrocities that occurs in the village. An air of mystery hangs over the movie and it isn't explicitly resolved. Revenge is one possible motive and the children, who move around together in a conspiratorial manner, are involved in some way. 'The White Ribbon' is a spellbinding movie, as exciting as a thriller which, indeed, it resembles. Among other things, it's about an unjust social system, yoked to a repressive society that is morally and physically disintegrating, though no one's prepared to confront it. The Baron tyrannises his young wife as if it were his right. In the name of his narrow religion the Pastor thrashes and humiliates his children. The Doctor's transgressive conduct involves his daughter and the midwife. The final long-held shot is an unforgettable tableau of the villages, gathered in a small bare church just after the outbreak of war, a nation on the point of history.

Philip French, The Observer - November 2009

Our guide in Michael Haneke's haunting film is the village schoolteacher, an earnest, chubby-faced bumbler and in voice-over narration, a ruminative old man. This teacher is by far the most benign – if ineffectual – authority figure in a place that turns out to be a veritable theme park of patriarchal abuses. The wholesome façade of this German hamlet masks a carnival of cruelty. Children are beaten and molested. Women are silenced and humiliated. Workplace accidents claim the lives of innocent farm wives. Horses and house pets are maimed. The only force more fearsome than the brutality of fathers is the innocence of children. In due course, we enter the homes of the Baron, the Doctor, the Steward, a tenant farmer and perhaps, most important, the Pastor. Each of these men represents a different face of power. Each one manifests his own special branch of awfulness, mistreating those close to him with methods appropriate to his station. Monstrous as these fathers are, their children may be worse. Haneke does not believe in the blamelessness of youth. Children, in this world, carry the sins of their parents in concentrated, highly toxic form and are also capable of a pure motiveless, experimental evil.

A.O. Scott, New York Times - December 2009

What you thought about The White Ribbon

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 (43%) | 20 (45%) | 3 (7%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 44 Film Score (0-5): 4.27 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

There was an appreciative and thoughtful response to Michael Haneke’s darkly disturbing film, with its picture of an apparently stable village where a series of accidents and atrocities take place. The film was described as ‘enthralling’, ‘intriguing’, powerful and disturbing’, ‘gripping and terrifying’ and ‘full of fear and foreboding’. The atmosphere of the film was noted in several comments, ‘sinister’, ‘evil’, ‘oppressive, ‘darkly secret and unhealthy’ and there was praise for the imaginative and subtle camerawork and the use of black and white. The contrast between the set-piece beauties of the landscape (harvest-time, the village in winter) and the ‘troubled oppressions’ within the village itself struck several of you as being a key dimension of the film’s impact. For some, the cruel and irrationally barbaric events were the direct consequence of ‘a brutal and brutalising obsession with social order and discipline’ and with ‘a bullying, repressive religion’. Also, ‘unsettling’ for some viewers was the treatment meted out to women by men, no matter what the social class, and that the only kind and gentle man in the community was the ineffective school teacher. The overall ‘cruelty and joylessness’ of the social world portrayed, prompted in some responses ‘a series of speculations’ which were in themselves highly worthwhile. For one viewer the film had allegorical dimensions, whereby the village was a symbol for German society then (1914) and twenty years later. There was general praise for the acting and in particular for the children, who maintained an ‘impassive, sinister, knowing innocence’. Some reservations were woven through the broadly positive reactions. For some viewers, it was too long and was confusing both in events and in its conclusion. The ending (or lack of it) was felt by a number of you to be unsatisfactory. One viewer felt that in a sense the grim atmosphere was overdone – ‘could no-one in a village community stand up for justice and good sense’? Another comment recognised the film’s ‘power and authenticity’ but ‘could not enjoy one minute of it’.