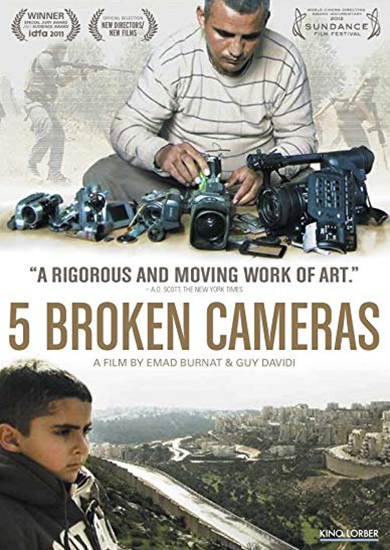

5 Broken Cameras

A Palestinian farmer's nonviolent resistance to the occupying Israeli army, told through the story of his cameras. Powerful and contemporary documentary.

Film Notes

‘5 Broken Cameras’ provides a grim reminder of the bitter intractability of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. A chronicle of protest and endurance, punctuated by violence and tiny glimmers of hope, this documentary is unlikely to persuade anyone with a hardened view of the issue to think again. However, the movie is necessary, if difficult, viewing. While it is hardly neutral, ‘5 Broken Cameras’ is more than another polemic from an embattled region. It is a visual essay in autobiography and a modest, moving and rigorous work of art. In 2005, the Israeli army began building a barrier between the village of Bilin and a nearby Jewish settlement. The residents of Bilin, outraged as their olive groves were bulldozed by the military, organised weekly protests attended by left-wing Israelis and sympathisers from other countries. In 2007, the Israeli Supreme Court ordered the barrier re-routed and four years later, village access to some of the land was restored. The footage Mr. Burnat shot, accompanied by after-the-fact voice over, is especially poignant and intimate. He and Mr. Davidi, an Israeli filmmaker, condensed hundreds of hours of images into the narrative. The encounters between the soldiers and the demonstrators have ritualistic qualities, but consequences could hardly be more serious. There are injuries and several deaths. Mr. Burnat is philosophical, even when his pain and indignation are at their height. He lives through periods of anxiety and horror and yet remains attuned to the fine grain of everyday experience. ‘5 Broken Cameras’ deserves to be appreciated for its lyrical delicacy and its precision. The political crisis which both unites and separates Mr. Burnat and Mr. Davidi is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon, but even in the midst of crisis, there is more than just politics to be seen and understood.

A.O. Scott – The New York Times - May 2012

When Palestinian farmer Emad Burnat bought a video camera in 2005, it was to film his newborn son. Around the same time, the Israeli army began building a ‘security fence’ in his village, to cordon off land and to build Israeli houses. The villagers started a peaceful protest against the bulldozers and Burnat became their unofficial cameraman. He has edited five years of footage into this documentary – a tough watch that will leave you despairing of peace any time soon. This is one man, in one Palestinian village, watching his son take his first steps and observing his friends protest – and die. But it is incredibly moving (his son’s early words include ‘army’ and ‘cartridge’) and it cuts through the them-and-us politics of the conflict to the struggles of daily life.

Cath Clarke – Time Out - 2012

What you thought about 5 Broken Cameras

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 (56%) | 23 (37%) | 4 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 63 Film Score (0-5): 4.46 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

Emad Burnat’s ‘5 Broken Cameras’, a powerful chronicle of protest from a embattled Israeli/Palestinian West Bank, provoked much reflection in the audience, as members felt “drawn into the daily reality of Palestinian life hitherto unknown”. It was, for many “very difficult to watch because of its violence and barbarism” and the “domestic background and context”, “so often missing from international political debate”, “added an extra poignancy”, particularly because of the children. The “bravery and solidarity” of the Palestinian villagers struck many in the audience, several noting “such courage and eternal optimism in the face of hideous and brutal injustice”. One member contrasted the “helplessness and violence” of the situation with our own “complacent security in our homes”. Several members felt that the film should be “compulsory viewing for all politicians – the arrest of children and shooting a prisoner in the leg are beyond disgust”. One member noted not only the cruelty and injustice of the situation but the expansion of an “aggressive Israeli urbanisation at the expense of the traditional agrarian Palestinian way of life”, with “the burning of olive trees as a powerful and distressing image of what it entails”. The “authenticity and detail” of the film record struck many of you, particularly given the time scale of events over five years. One member noted that the young Israeli conscripts were honestly and sensitively portrayed in the footage, making them too, victims of a “brutalising process”. There were some criticisms made too. One member of the audience would have welcomed a “wider historical context” to the establishment of the occupied territories. Another response felt that the film “showed nothing really new” and feared that the children were being trained as “the next generation of martyrs”. There was the feeling too that it was “only one-sided polemic” and that a film society should not show ‘propaganda’. There were sad reflections for many of you, that the problem seemed irresolvable, that further conflict was inevitable and that might would continue to be right. One member hoped, rather forlornly, that the Israeli government, after all the bitter experience of the Holocaust, might learn to behave better.