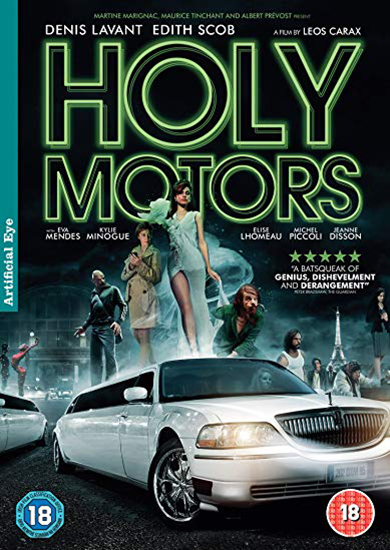

Holy Motors

The mysterious and shadowy life of Monsieur Oscar, by turns playing roles from captain of industry to beggar, accompanied only by Celine, a slender blond, as they move through and around Paris.

Film Notes

Leos Carax, an immensely talented and highly self-conscious filmmaker, has made in ‘Holy Motors’ a dreamlike and richly allusive movie which is destined to become a classic. All Carax’s pictures hitherto have been about young people choosing to live outside conventional society. In this film the central character, played by the somewhat sinister Denis Lavant, is older and the setting is Paris. The film opens with Carax himself waking or dreaming in the early hours and the created world which follows is seen entirely through his movie-educated eyes. The focus is on Denis Lavant, who leaves home, in the early hours to drive to Paris from his white art deco house shaped like a ship. He’s formally dressed, a businessman. His chauffeur is a handsome middle-aged woman (Edith Scob) called Celine. Rapidly we see that Oscar (Lavant) is a man of numerous aliases and identities who, with great dexterity transforms himself in the back of the car. As the cinematic and literary references (Cocteau, Bunuel, Godard) are scattered round like confetti, Lavant/Oscar becomes a series of bizarre incantations from an old crone begging by the Seine to the cheerful leader of an accordion band performing in a candlelit church. He’s the man of a thousand faces, the master of disguise. When asked why he does it by a chilling interrogator, he answers “for the beauty of the gesture”. What is certain is that he’s getting old, heading towards the grave and images of death and decay are everywhere. Borrowing from many sources, the film has an atmosphere all its own, a combination of the mysterious, the lucid and the pleasing reverie. It’s a happy return to the Cinema from the director and likely to prove the classic he has been hoping to make.

Philip French – The Observer - September 2012

Oscar (Denis Lavant), the film’s shape-shifting anti-hero, is a Rumpelstiltskin-type grotesque who in one bizarre incident bites off a photographer’s fingers before dragging a supermodel underground to dine on her hair in the nude. This is one of the many vignettes in Carax’s inscrutable story, a cinematic revolving door, constantly entered and exited by Oscar. He inserts himself into a series of role-playing scenarios of escalating outlandishness, his instructions fed him by a stoic limousine driver (Edith Scob). Weird and at times, absurd, yes but there’s something tender and truthful about Carax’s hall of mirrors – ecstatic, fizzy, idiotic and provocative.

Guy Lodge – Time Out - September 2012

What you thought about Holy Motors

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 (10%) | 20 (26%) | 14 (18%) | 16 (21%) | 20 (26%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 78 Film Score (0-5): 2.74 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

As the figures above show, for the first time this season the critical knives were out, for Leos Carax’s ‘Holy Motors’. Many of you, as in a notable sequence in the film, went for the jugular. “It was appalling and dull and uninteresting”, “bizarre and ridiculous”, “nasty brutish and far too long”, “painful, self-indulgent rubbish”, “just a director showing off”. It had, for many in the audience, “no rhyme or reason”, “no character”, “no dramatic tension”, “no points of contact with any general experience” and “no artistic coherence”. There was some admiration for a “clever theatricality, especially in make-up” but it still remained “very nasty” and “trying to be intelligent and not even beginning”. One response sums up the negative broadside: “Skilful playing on ambiguities does not make a great film. However well-crafted, shaped, gold-plated and bejewelled, an empty shell is still an empty shell” However, as we have come to expect, responses to film are never straightforward and strong negative responses can be countered by reactions of a very different kind, perceiving a range of insights and qualities. The same number of responses indicated that the film was ‘good’ as did that it was ‘very poor’, establishing a conversely positive view of the film. This “powerful, allegoric journey” was “rich, puzzling and fascinating” creating an “intriguing looking-glass world” with “multiple possibilities and interpretations”. It was “very refreshing and original” and made the viewer “get involved and do some thinking” instead of having the director dictate event and response. Indeed, the richness of ambiguities and alternatives was part of the attraction. “Desires, fears, repeating patterns, dream, nightmare, life and death”. For some it was “compellingly bizarre”, “disturbing and provocative”, “clever, weird but memorable for its strangeness”. It was, as one viewer found “great to make you think and throw you off balance ……challenging the norms” and for another “mesmerising surrealism….fascinating and enthralling”. One member of the audience found it a “Gallic Alice in Wonderland – surreal, bizarre but strangely enjoyable” More than one in the audience found a Shakespearean echo “one man in his time plays many parts”, in the events of the film and found “intelligence and purpose” in their portrayal. For those who enjoyed the film, it was “mind-stretching, hugely imaginative with some superb moments”. It is not easy to bridge the critical divide the film created but we can enjoy the debate and the contrasts in viewpoint. As William Blake wrote, “without contraries is no progression”.