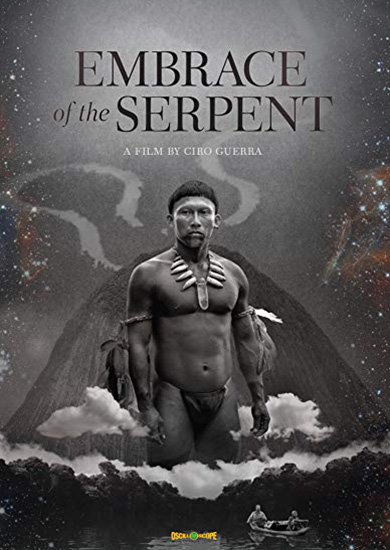

Embrace of the Serpent

The story of the relationship between Karamakate, an Amazonian shaman and last survivor of his people, and two scientists who work across the course of 40 years to search the Amazon for a sacred healing plant.

Film Notes

Every now and then, with great infrequency (alas), a film comes along that is like no other and completely knocks you for six, and that is Embrace of the Serpent. The first Colombian film to be nominated for an Oscar — it lost to Son of Saul, should you set any store by such things — it was filmed in the Colombian section of the Amazon basin, with a script developed in consultation with native tribes, and tells the story of a shaman’s encounters with two white scientist explorers, which unfold in different time periods. So far, so National Geographic; a world disappeared by colonialism and all that (sorry; our bad). But this is so powerfully imagined and realised, and so engrossing, and so painful, that the experience becomes one of bearing witness, cinematically, and if you’re not up to that? There is always Jennifer Aniston in Mother’s Day, which also opens this week, and sees Ms Aniston play ‘a stressed-out single mom who learns her ex-husband is marrying a younger woman’. Your call. It is written and directed by Ciro Guerra, a Colombian whose starting point was the real-life diary of Theodor Koch-Grünberg, the German ethnologist who first documented the Amazon in the early 1900s. The film opens during this time, with Karamakate (played by Nilbio Torres, as a young man) who, we quickly understand, is the last of his tribe, the rest having been wiped out by the rubber barons. He lives remotely in isolation and is squatting watchfully at the river’s edge, in all his gorgeous physicality — buttock cheeks hard enough to crack nuts with, I swear; even Brazils — when a canoe approaches carrying Theo (Jan Bijvoet) and his travelling companion, Manduca (Yauenku Migue), who was enslaved to the barons until Theo bought his freedom. But now Theo is deathly ill. Malaria, presumably. And they’d heard that Karamakate is a great healer. Will he help? No, says Karamakate. He will never help ‘a white’. But he’s talked into it when Theo tells him that there are survivors from his tribe, and he knows where they live. So they set off, to find Karamakate’s people, and also the yakruna, a rare flower, which, says Karamakate, will provide a permanent cure for Theo’s sickness. This is not a morally discreet film, or a politically timid one. In what is effectively a road trip by river, every stop along the way meets the devastation wrought by colonialism; the abuses of the rubber trade, the mutilated slave who begs to be shot, the destruction of the landscape, the Catholic priest who cruelly whips the orphaned children in his care. It is also told in tandem with a parallel story, set 40 years later, when yet another white scientist trucks up. This is Evan (Brionne Davis), a botanist who has read Grünberg’s diaries and also wishes to find the yakruna. He, too, enlists the help of Karamakate, who is now old (and played by Antonio Bolívar), and whose buttock cheeks are not so proud but who, after some reluctance, again complies. So it’s effectively a road trip, by river, made twice. However, simply informing you what happens, incident by incident, does the film a massive disservice, as it does not reveal the depth of Guerra’s vision, or the beauty of that vision, as realised via strangely lush black-and-white compositions that burst into colour, only momentarily and hallucinogenically, at the very end. And it’s not simply one diabolical evil after another. There is nuance, as when a tribal chief steals Theo’s compass, and Theo becomes angry, saying a compass will erode the native know-how of celestial navigation, and it’s the two worlds looking each other up and down, until Karamakate says fatalistically: ‘You cannot forbid them to learn.’ Although this will likely be compared to Roland Joffé’s The Mission and Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, it isn’t, in fact, similar to either as here neither the film-maker nor the protagonist is a white European — this is the inside looking out, rather than the outside looking in — and also no extra was paid a dollar a day to pull a ship over a hill and die for his trouble. This is extraordinary, audacious cinema that comes at its subject from a unique angle and is compellingly interesting for every minute of its two, colossally sad hours. But, like I said, if you aren’t up to it there is always Mother’s Day, which co-stars Kate Hudson as ‘a fitness freak who doesn’t tell her parents she has a family’. Your call.

Deborah Ross, The Spectator, 11 June 2016

“The horror! The horror!” The terminal valediction of Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” is deconstructed with a raging eloquence in the Colombian director Ciro Guerra’s majestic, spellbinding film, “Embrace of the Serpent.” Is the unspeakable savagery evoked by his dying words really beyond the reach of the civilized imagination? I doubt it. That tricky word “civilized” connotes enlightenment, behavioral restraint, evolutionary advancement and the suppression of bestial impulses. But what is so civilized about mass slaughter, torture and planetary despoliation in the name of anything or anybody? It shouldn’t have taken a journey up the Congo River for a white man to discover the evil within. That is the uncomfortable truth at the core of Mr. Guerra’s tragic cinematic elegy for vanished indigenous civilizations in the Amazon jungle. Viewed largely through the aggrieved eyes of a shaman whose tribe is on the verge of extinction at the hands of Colombian rubber barons in the 19th and 20th centuries, “Embrace of the Serpent,” a fantastical mixture of myth and historical reality, shatters lingering illusions of first-world culture as more advanced than any other, except technologically. The director’s third film, it is the more remarkable for being shot in black and white, with one brief color sequence near the end. Beautiful isn’t a strong enough word to describe its scenes of the heaving waters of the Amazon and its tributaries, on which two explorers, separated by more than 30 years, navigate in canoes, accompanied by a shaman, Karamakate. The film’s central figure, he is the last survivor of the Cohiuano, an Amazonian tribe killed off by the rubber barons. He is no innocent, noble savage but an angry, morally complex individual with a heart full of grief. He may be in greater harmony with the natural world than any foreign intruder, but he is alone. The film gives full voice to his view of a social order in which the rules of nature assimilated and handed down through the centuries among the Cohiuano must be obeyed, or else. The Amazonian ecosystem, in which everything seemingly preys on everything else, is a continual and endless feeding frenzy. In a signature image, an aquatic serpent devouring another snake is observed by a glowering jaguar. Inspired by the travel journals of Theodor Koch-Grünberg, a.k.a. Theo (Jan Bijvoet), a German ethnologist and explorer, and Richard Evans Schultes, a.k.a. Evan (Brionne Davis), an American biologist considered the father of modern ethnobotany, the film imagines their parallel journeys, decades apart, seeking the yakruna, a sacred healing plant. This miraculous cure-all is a hallucinogen that attaches itself to rubber trees. In Karamakate’s eyes, the European and American marauders who enslaved and destroyed his tribe are agents of an insane culture devoted to genocidal conquest and rapacious destruction. He finds the concept of money laughable; it is just useless paper. He urges the explorers to throw their luggage overboard. Their possessions are “just things,” he scoffs. To the extent that the film persuades you that he is right, “Embrace of the Serpent” is potentially life-changing. One thing Evan refuses to relinquish is a portable phonograph on which he plays a recording of Haydn’s “Creation.” Karamakate responds respectfully to the sublime music. The first journey takes place in 1909, when Theo is near death. (Koch-Grünberg actually died in 1924). Accompanied by the young Karamakate (Nilbio Torres), he is escorted by canoe up the Amazon River with a guide, Manduca (Yauenkü Miguee), who had worked on a rubber plantation and was freed by Theo. In a movie in which nine languages are spoken, Manduca is the cultural mediator and sometime interpreter. Initially reluctant to help Theo find a yakruna, Karamakate agrees to only if Theo will help him locate other surviving members of the Cohiuano, who he says exist. Later, Evan makes the same journey with the older, enfeebled Karamakate (Antonio Bolívar Salvador), whose tribe is now extinct. Karamakate has lost his ability to communicate with rocks and trees and is weighed down by a resigned sadness. The movie jumps between the two journeys, which follow roughly identical routes. The film’s anger is concentrated in two devastating scenes of tyrannical white intruders. At a Roman Catholic mission, a Spanish priest presides over a flock of boys orphaned by the conflicts between rubber barons and indigenous tribes. Dressed in white robes and forbidden to speak “pagan languages,” the boys are viciously whipped at the whim of this Dickensian monster. Decades hence, at another riverside community, the dying indigenous wife of a self-proclaimed white messiah is healed by one of Karamakate’s potions, and her husband proclaims himself the Son of God. In a delirium, he invites his followers to consume his body and blood. As they encircle him like vultures, the visitors flee. From here, the film moves to mystical higher ground, as abhorrence expands into awe. Instead of “The horror!,” I would substitute “The wonder!”

Stephan Holden, The New York Times, FEB. 16, 2016

What you thought about Embrace of the Serpent

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 (43%) | 28 (40%) | 10 (14%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 70 Film Score (0-5): 4.23 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

As I have commented in the past, I have been astonished by how many of you are able to deliver concise views of the film you have just watched a mere few minutes afterwards. However, this was not universally the case with Embrace of the Servant which, while it was considered by many of you “an amazing film”…with “marvellous scenery and photography and music” it also gave rise to this oft quoted cry “I don’t know that I understood all of it”. One commented that they considered it “thought provoking, fascinating but ultimately baffling”. “Good in parts. Probably the most extraordinary film I have seen. Strange, puzzling, very atmospheric and dreamlike. I could not believe it was a true story!” “I need a week to think about it”. “Puzzling”. And again the refrain “I didn’t understand it all – but what an experience”. One reviewer told us that in their opinion “It flowed like the great river, with depths and treacherous, unexpected currents as it carried one along”... “I felt, as I know I was meant to, that much was beyond my understanding and made me realise how much more there is to understand….Brilliant!” However others thought it “a fascinating film that showed all too clearly the ways cultures fail to comprehend each other’s beliefs” which was “very thought provoking and tragic in so many ways”. “A bit too long, but a memorable and enlightening exploration of the deplorable impact we have had on the planet and its people”. “Wonderful – deeply moving and thought provoking. If only we had the gift to respect other cultures”. “Mesmerising”. “A wonderful mix of culture clash, unbelievable mysticism, romance, economic dilemma, tyranny and love”. “Turns out that the “cannibals” had it right all along. Viva Las Prohibiciones. An ode to discipline and respecting our planet”. “An enigmatic film in part but shows the deprivations of progress”. The choice by the filmmakers to shoot in Black and White prompted numerous observations. Although one of you considered this “an astonishing film” you also “longed for colour but was shocked when it came…” and another said that they “liked the B+W as opposed to colour. It gave it a different dimension”. “I found it ultimately disappointing and tiresome and longed to see the colour of the jungle”. “A beautiful, thought provoking film. The jungle was terrifying because everything was hidden. The only obvious thing was the inhuman behaviour of man to man fed by greed. It was a wonderful experience, black and white was best. It left me feeling very sad”. “Which drugs were they on? Poor continuity spoilt a good trip”. “A fascinating film – amazing photography and music to evolve the mystery and sadness of a vanishing society. A wonderful study of culture clash. There is so much we do not understand. I was once cured by a shaman”. “Haunting take on a familiar parable. The finale particularly good. Reminiscent of all of the “Heart of Darkness” inspired movies”.