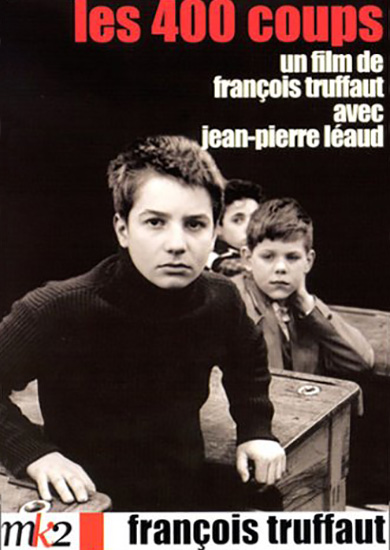

The 400 Blows

Intensely touching story of a misunderstood youth who, left without attention, delves into a life of petty crime. Arguably Francois Truffaut’s finest, with one of the most memorable endings in film.

Film Notes

LET it be noted without contention that the crest of the flow of recent films from the "new wave" of young French directors hit these shores yesterday with the arrival at the Fine Arts Theatre of "The 400 Blows" ("Les Quatre Cents Coups") of Françcois Truffaut. Not since the 1952 arrival of René Clement's "Forbidden Games," with which this extraordinary little picture of M. Truffaut most interestingly compares, have we had from France a cinema that so brilliantly and strikingly reveals the explosion of a fresh creative talent in the directorial field. Amazingly, this vigorous effort is the first feature film of M. Truffaut, who had previously been (of all things!) the movie critic for a French magazine. (A short film of his, "The Mischief Makers," was shown here at the Little Carnegie some months back.) But, for all his professional inexperience and his youthfulness (27 years), M. Truffaut has here turned out a picture that might be termed a small masterpiece. The striking distinctions of it are the clarity and honesty with which it presents a moving story of the troubles of a 12-year-old boy. Where previous films on similar subjects have been fatted and fictionalized with all sorts of adult misconceptions and sentimentalities, this is a smashingly convincing demonstration on the level of the boy—cool, firm and realistic, without a false note or a trace of goo. And yet, in its frank examination of the life of this tough Parisian kid as he moves through the lonely stages of disintegration at home and at school, it offers an overwhelming insight into the emotional confusion of the lad and a truly heartbreaking awareness of his unspoken agonies. It is said that this film, which M. Truffaut has written, directed and produced, is autobiographical. That may well explain the feeling of intimate occurrence that is packed into all its candid scenes. From the introductory sequence, which takes the viewer in an automobile through middle-class quarters of Paris in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, while a curiously rollicking yet plaintive musical score is played, one gets a profound impression of being personally involved—a hard-by observer, if not participant, in the small joys and sorrows of the boy. Because of the stunningly literal and factual camera style of M. Truffaut, as well as his clear and sympathetic understanding of the matter he explores, one feels close enough to the parents to cry out to them their cruel mistakes or to shake an obtuse and dull schoolteacher into an awareness of the wrong he does bright boys. Eagerness makes us want to tell you of countless charming things in this film, little bits of unpushed communication that spin a fine web of sympathy—little things that tell you volumes about the tough, courageous nature of the boy, his rugged, sometimes ruthless, self-possession and his poignant naïveté. They are subtle, often droll. Also we would like to note a lot about the pathos of the parents and the social incompetence of the kind of school that is here represented and is obviously hated and condemned by M. Truffaut. But space prohibits expansion, other than to say that the compound is not only moving but also tremendously meaningful. When the lad finally says of his parents, "They didn't always tell the truth," there is spoken the most profound summation of the problem of the wayward child today. Words cannot state simply how fine is Jean-Pierre Leaud in the role of the boy—how implacably deadpanned yet expressive, how apparently relaxed yet tense, how beautifully positive in his movement, like a pint-sized Jean Gabin. Out of this brand new youngster, M. Truffaut has elicited a performance that will live as a delightful, provoking and heartbreaking monument to a boy. Playing beside him, Patrick Auffay is equally solid as a pal, companion in juvenile deceptions and truant escapades. Not to be sneezed at, either, is the excellent performance that Claire Maurier gives as the shallow, deceitful mother, or the fine acting of Albert Remy, as the soft, confused and futile father, or the performance of Guy Decomble, as a stupid and uninspired schoolteacher. The musical score of Jean Constantin is superb, and very good English subtitles translate the tough French dialogue. Here is a picture that encourages an exciting refreshment of faith in films.

By BOSLEY CROWTHER New York Times. November 17, 1959

Calling The 400 Blows a "coming-of-age story" seems somehow inadequate. The label, while accurate, does not indicate either the uniqueness or the cinematic importance of this motion picture. These days, the average coming-of-age story tends to be a lightweight affair, often tinged with nostalgia and rarely perceptive. Such is not the case with The 400 Blows, which takes an uncompromising, non-judgmental look at several key events in the life of a teenage boy. With all of the melodrama leeched out, we are able to view and understand the factors that shape his present and the direction of his future. The title, Les quatre cent coups is literally translated as The 400 Blows; however, since it's an idiom, a direct translation is imperfect. The phrase loosely means "Raising Hell", and, while that's not an English interpretation, it's a reasonable approximation. The 400 Blows sounds like a movie about violence and abuse, or (if you're thinking in sexual terms) something salacious. When the film opened in the late '50s, more than a few viewers were treated to an entirely different experience from what they expected. (A widely circulated, possibly apocryphal story says that the Weinstein brothers attended this movie expecting a sex flick. They were so astounded by what they saw that their entire perspective on cinema changed, eventually leading them to found Miramax.) The 400 Blows is the debut outing for celebrated French director François Truffaut, who arrived in the filmmaking arena after taking a detour through film criticism. (During the years when he wrote for André Bazin's "Cahiers du Cinéma," Truffaut developed a reputation as being an acerbic, unforgiving critic.) Along with Godard, Rohmer, Malle, Vadim, and Chabrol (amongst others), Truffaut was one of the founding auteurs of the French "New Wave" cinema - a philosophy that sought to enliven the Gaelic motion picture industry by taking bold chances and telling personal stories. The 400 Blows became one of the first and most influential of the French New Wave films (it was released around the same time as Godard's Breathless), and, as such, was at the vanguard of a movement that had a worldwide impact on movie-making for more than a decade. The 400 Blows is the first of five times Truffaut brings us a chapter in the life of his cinematic alter-ego, Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud). Doinel (recurrently played by Léaud) would return four more times: in the 1962 short film "Antoine and Collette", then in the features Stolen Kisses (in 1968), Bed and Board (in 1970), and Love on the Run (1979). Love on the Run seems to close the Doinel cycle, but, because Truffaut died in 1984, there's no way to tell whether he might have again returned to this character. It's interesting to note that, while the Doinel of The 400 Blows bore a striking resemblance to Truffaut at 14, by the time of Love on the Run, the gulf between the character's life and his creator's had widened considerably. Antoine is not so much of a troublemaker as he is unlucky. His exploits, at least early in the film, are no different from those of his school classmates - except he's the one who gets caught and punished. For example, when a pin-up is being passed around, the teacher notices it when it's on Antoine's desk. Once Antoine has earned his teacher's disapproval, he has placed himself in a bad position - one that is exacerbated when he fails to do his homework, then tells a foolhardy lie that is easily disproven. Still, many of Antoine's school infractions are minor. It's just that the authority figures see them in the worst possible light. Even when Antoine tries to do something right, it turns out wrong. On one occasion, he writes an essay inspired by and in the style of Balzac. His teacher accuses him of plagiarism. Antoine's home life isn't much better. His mother (Claire Maurier), who gave birth to Antoine after an unwanted pregnancy, spends as much time away from home as she can. When she's with her son, she has difficulty controlling her impatience with him. His stepfather (Albert Rémy) is sometimes friendly and companionable, but, on other occasions, he's short-tempered and grumpy. Neither parent seems to care much about what happens to Antoine. To them, he's an inconvenience who cannot be ignored. When something goes wrong at school, they immediately adopt the teachers' position without listening to Antoine's perspective. One day when he gets in trouble, he deduces that it would be better to run away than go home. By the end of The 400 Blows, Antoine is a juvenile delinquent. He has stolen a typewriter from his father's office (he is caught not when he steals it but when he foolishly tries to return it), been arrested by the police, and escaped from reform school. Antoine's life could have taken a turn for the better at any time had someone shown an interest in him - his mother, his father, or a teacher. But he is a victim of his circumstances, which are framed by neglect. Antoine gains no respite at home or in school. In fact, the only time he seems to be at peace is when he's in a movie theater, free to escape to another world for a finite period of time. The 400 Blows is a portrait of innocence lost, as Truffaut is careful to point out. One scene in particular highlights this. We are treated to an extended series of shots of dozens of children gleefully watching a puppet show. Many of their faces are alight with innocent excitement. But Antoine has no interest in such childish things. While the others around him laugh and enjoy the show, he and his friend plot how to get more money. He has moved into the seedy side of the adult world: petty crime and its associated punishment - being locked in a cage. When he is in jail, he is treated as coldly as a hardened criminal. Stylistically, The 400 Blows takes a number of intriguing chances. For the most part, Truffaut and cinematographer Henri Decaë go for a simple (but never simplistic) approach, but there are some radical innovations and adaptations. In the first place, The 400 Blows was the first French film to be shot in widescreen (aspect ratio 2.35:1), and this required much planning on Truffaut's part. The scene where Antoine speaks to the psychologist heightens the pseudo-documentary feel that shadows the entire production. Because we never see the questioner, it's as if Antoine is speaking directly into the camera, explaining his life and the reasons he is in his current predicament. Finally, there's the film's closing image: an optical zoom on a freeze-frame. This often-copied effect was not pioneered by Truffaut (it was, in fact, an homage to something similar in Ingmar Bergman's Monika), but this is the film that "popularized" it. For all of Truffaut's mastery of the behind-the-camera aspects of The 400 Blows, an equal share of the credit must go to lead actor Jean-Pierre Léaud. One of the reasons Truffaut chose Léaud for this role is that he shared some characteristics in common with Antoine, such as his disdain for school and his tendency to be a troublemaker. In this role, Léaud is fantastic. There's never a sense that he is acting - every movement, word, and thought comes across as natural, not forced. He is not on-screen for every moment of the film (there are three "interludes" where Antoine is largely or completely absent - the classroom scene after he has been sent out, the defection from the gym teacher's jog through Paris, and the puppet show), but, when he is present, he compels the viewer's attention. Léaud's standout scene is probably the interview with the psychologist, where Antoine's fidgety reactions are perfect. There's no question that The 400 Blows stands out when compared to other coming-of-age dramas. Even though more than forty years have elapsed since the film's release, its effect has neither faded nor been duplicated. By eschewing manipulation and sentimentality, Truffaut does not invite false emotions and insincere pity. Instead, his clear-eyed approach presents Antoine to us with all of his faults and foibles on display. He is not "sanitized" to shade our response. Yet, because Truffaut's style is so honest, we develop a deeper connection with Antoine that we would have in a traditional melodrama. And, when that final shot occurs, leaving Antoine suspended in time, with his future uncertain, our reaction is unforced. Of course we can now do what viewers could not in 1959 - look through other windows on different phases of Antoine's life and see how far he comes from the bored, uncertain boy presented here. The 400 Blows remains a remarkable film. As with all of the great classics, the passage of time only causes us to appreciate it more.

James Berardinelli ReelViews August 1, 2002

Offbeat pic gets deep into the life of a 12-year-old boy, his disorientation with school and parents, and his final commitment to, and escape from, an institution. It eschews conventional blames and emerges an engaging, moving film. Boy has a mother who cheats on his weak father. One day he runs off when, to explain a truancy, he suddenly makes up a tale that his mother is dead. He steals something and is committed to an institution as his parents wash their hands of him. Pic ends with his dash to freedom. Moppets are well-handled and adults properly one-dimensional in this astute look at the child’s world. Young director Francois Truffaut [scripting from his own original story] still lacks form and polish but emerges an important new director here. Technical qualities are uneven but blend with the meandering but sensitive look at a child’s world and revolt.

Variety Staff DECEMBER 31, 1958

What you thought about The 400 Blows

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 (29%) | 33 (42%) | 20 (26%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 78 Film Score (0-5): 3.97 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

In my introduction to the film I mentioned that the critic, James Berardinelli had written that the title, “Les quatre cent coups” is literally translated as The 400 Blows; however, since it's an idiom, a direct translation is imperfect. The phrase loosely means "Raising Hell", and, while that's not an English interpretation, it's a reasonable approximation”. One observer commented that in their opinion, “It was the 400 blows – although the parents never physically beat him! So harrowing to watch the erosion of hope and the weary resignation of his tender years. His friend’s loyalty was heartening….I hope he found what he was searching for”. Many of you were equally emotionally invested in the story which reflected a “sad portrayal of the power adults (negative in this case) have over children without them even realising” and “a rather shocking depiction of a normal little boy descending into turmoil and oblivion” which was “bleak but powerful storytelling”. Others agreed telling us that it was “a moving film showing the vulnerability of unloved children”. Many of you were taken with the portrayal of late 50’s Paris with several people commenting on this “fascinating vignette of post war Parisian family life…where people were “trying to make the best of things with few means….seeing the lack of proper discipline letting the teens slip through towards crime” and one commented on the emotional impact of “Paris seen through the bars of the prison van and Antoine’s tears when he realises his freedom had been taken away”. Others just “loved seeing the old cars of 1959.” There were many positive comments about the acting and Truffaut. Typical were; “hopefully we will be able to see the other films with Jean-Pierre Léaud” who played Antoine and “there must be a sequel?” In the review by James Berardinelli on the website he tells us that “The 400 Blows is the first of five times Truffaut brings us a chapter in the life of his cinematic alter-ego, Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud). Doinel (recurrently played by Léaud) would return four more times: in the 1962 short film "Antoine and Collette", then in the features Stolen Kisses (in 1968), Bed and Board (in 1970), and Love on the Run (1979). Love on the Run seems to close the Doinel cycle, but, because Truffaut died in 1984, there's no way to tell whether he might have again returned to this character”. … A member asked “is the end of “Quadrophenia”, a reference to the end here?” The answer is yes. In the Criterion Collection reviews, Frank Roddam, the director, says “Truffaut reportedly said his film was to be judged on its sincerity rather than its technical merit. The film is beautifully made, but Truffaut’s sincerity confirmed my path as a filmmaker. The 400 Blows strongly influenced my films Mini and Quadrophenia.” A few last observations which caught my attention were “a superb study of innocence destroyed by indifference and cruelty at all turns. Stunning camera work which opened up a new chapter in emotional narrative within cinema” and “I was looking forward to this as I’d seen it once before, many years ago, and found it disappointing despite being a big fan of Truffaut’s other work. I loved it this time.” Many thanks to you all for taking the time to complete the opinion slips. I am sorry if I have not included your particular observation but as you can see we are limited for space here.