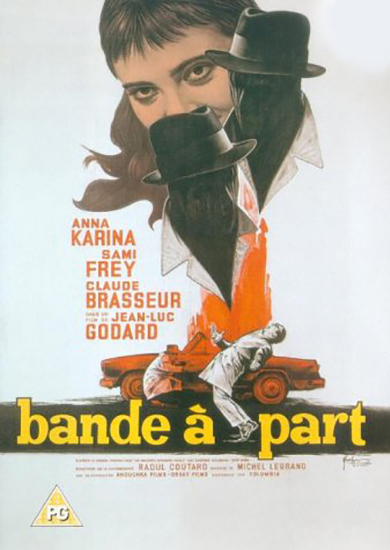

Bande à Part

Two crooks, with a fondness for old Hollywood B-movies, convince a language student to help them commit a robbery. A stylised, jazzy and poetic take on the modern crime film, it's also one of the most influential films of the French New Wave. Contains one of the most iconic dance scenes in film.

Film Notes

Jean-Luc Godard intended to give the public what it wanted. His next film was going to be about a girl and a gun — ”A sure-fire story which will sell a lot of tickets.” And so, like Henry James’ hero in The Next Time he proceeded to make a work of art that sold fewer tickets than ever. What was to be a simple commercial movie about a robbery became Band of Outsiders. The two heroes of Band of Outsiders begin by play-acting crime and violence movies, then really act them out in their lives. Their girl, wanting to be accepted, tells them there is money in the villa where she lives. And we watch, apprehensive and puzzled, as the three of them act out the robbery they’re committing as if it were something going on in a movie—or a fairy tale. The crime does not fit the daydreamers nor their milieu: We half expect to be told it’s all a joke, that they can’t really be committing an armed robbery. Band of Outsiders is like a reverie of a gangster movie as students in an expresso (sic) bar might remember it or plan it—a mixture of the gangster film virtues (loyalty, daring) with innocence, amorality, lack of equilibrium. It’s as if a French poet took an ordinary banal American crime novel and told it to us in terms of the romance and beauty he read between the lines; that is to say, Godard gives it his imagination, recreating the gangsters and the moll with his world of associations—seeing them as people in a Paris cafe, mixing them with Rimbaud, Kafka, Alice in Wonderland. Silly? But we know how alien to our lives were those movies that fed our imaginations and have now become part of us. And don’t we—as children and perhaps even later—romanticize cheap movie stereotypes, endowing them with the attributes of those figures in the other arts who touch us imaginatively? Don’t all our experiences in the arts and popular arts that have more intensity than our ordinary lives, tend to merge in another imaginative world? And movies, because they are such an encompassing, eclectic art, are an ideal medium for combining our experiences and fantasies from life, from all the arts, and from our jumbled memories of both. The men who made the stereotypes drew them from their own scrambled experience of history and art—as Howard Hawks and Ben Hecht drew Scarface from the Capone family “as if they were the Borgias set down in Chicago.” The distancing of Godard’s imagination induces feelings of tenderness and despair which bring us closer to the movie-inspired heroes and to the wide-eyed ingenue than to the more naturalistic characters of ordinary movies. They recall so many other movie-lives that flickered for us; and the quick rhythms and shifting moods emphasize transience, impermanence. The fragile existence of the characters becomes poignant, upsetting, nostalgic; we care more. This nostalgia that permeates Band of Outsiders may also derive from Godard’s sense of the lost possibilities in movies. He has said, “As soon as you can make films, you can no longer make films like the ones that made you want to make them.” This we may guess is not merely because the possibilities of making big expensive movies on the American model are almost non-existent for the French but also because, as the youthful film enthusiast grows up, if he grows in intelligence, he can see that the big expensive movies now being made are not worth making. And perhaps they never were: The luxury and wastefulness that, when you are young, seem as magical as peeping into the world of the Arabian Nights, become ugly and suffocating when you’re older and see what a cheat they really were. The tawdry American Nights of gangster movies that were the magic of Godard’s childhood formed his style—the urban poetry of speed and no afterthoughts, fast living and quick death, no padding, no explanations—but the meaning had to change. An artist may regret that he can no longer experience the artistic pleasures of his childhood and youth, the very pleasures that formed him as an artist. Godard is not, like Hollywood’s product producers, naïve (or cynical) enough to remake the movies he grew up on. But, loving the movies that formed his tastes, he uses this nostalgia for old movies as an active element in his own movies. He doesn’t, like many artists, deny the past he has outgrown; perhaps he is assured enough not to deny it, perhaps he hasn’t quite outgrown it. He reintroduces it, giving it a different quality, using it as shared experience, shared joke. He plays with his belief and disbelief, and this playfulness may make his work seem inconsequential and slighter than it is: It is as if the artist himself were deprecating any large intentions and just playing around in the medium. Reviewers often complain that they can’t take him seriously; when you consider what they do manage to take seriously, this is not a serious objection. Because Godard’s movies do not let us forget that we’re watching a movie, it’s easy to think he’s just kidding. Yet his reminders serve an opposite purpose. They tell us that his aim is not simple realism, that the lives of his characters are continuously altered by their fantasies. If I may be deliberately fancy; he aims for the poetry of reality and the reality of poetry. I have put it that way to be either irritatingly pretentious or lyrical—depending on your mood and frame of reference, in order to provide a critical equivalent to Godard’s phrases. When the narrator in Band of Outsiders says, “Franz did not know whether the world was becoming a dream or a dream becoming the world” we may think that that’s too self-consciously loaded with mythic fringe benefits and too rich an echo of the narrators of Orphée and Les Enfants Terribles, or we may catch our breath at the beauty of it. I think those most responsive to Godard’s approach probably do both simultaneously. We do something similar when reading Cervantes. Quixote, his mind confused by tales of Knight Errantry, going out to do battle with imaginary villains, is an ancestor of Godard’s heroes, dreaming away at American movies, seeing life in terms of cops and robbers. Perhaps a crucial difference between Cervantes’ mock romances and Godard’s mock melodramas is that Godard may (as in Alphaville) share some of his characters’ delusions. It’s the tension between his hard, swift, cool style and the romantic meaning that style has for him (and for other lovers of “unsentimental”—!—American gangster movies) that is peculiarly modern and exciting in his work. It’s the casual way he omits mechanical scenes that don’t interest him so that the movie is all high points and marvelous (sic) “little things.” Godard’s style, with its nonchalance about the fates of the characters—a style drawn from American movies and refined to an intellectual edge in post-war French philosophy and attitudes—is an American teenager’s ideal. To be hard and cool as a movie gangster yet not stupid or gross like a gangster—that’s the cool grace of the privileged, smart young. It’s always been relatively respectable, and sometimes fashionable, to respond to our own experience in terms drawn from the arts: To relate a circus scene to Picasso, or to describe the people in a Broadway delicatessen as an Ensor. But until recently, people were rather shamefaced or terribly arch about relating their reactions in terms of movies. That was more a confession than a description. Godard brought this way of reacting out into the open of new movies at the same time that the Pop Art movement was giving this kind of experience precedence over responsiveness to the traditional arts. By now—so accelerated has cultural history become—we have those students at colleges who when asked what they’re interested in say, “I go to a lot of movies.” And some of them are so proud of how compulsively they see everything in terms of movies and how many times they’ve seen certain movies that there is nothing left for them to relate movies to. They have been soaked up by the screen.

PAULINE KAEL, The New Republic, September 10, 1966

It's no bad thing, meanwhile, to be reminded of the early playfulness of the director film buffs call 'God' for short. Godard is now 70, and Bande à Part, re-released in a new print as part of the retrospective at the NFT, was made in 1964. It's dated only in that it makes you feel, as you watch the happy trio of Anna Karina, Claude Brasseur and Sami Frey running through the Louvre, dancing in cafés and singing in the Metro, that people had more fun in the Sixties. Bande à Part is light, silly and cool, with none of the ponderousness of Contempt, made the year before. But, of course, it's not the Sixties; the characters in the film live in a parallel world, play-acting shootouts from Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, and wanting to live their life as if it were only a movie. Later, they arm their games with real guns and all hell breaks loose. But there's still not much that's tragic about it because, after all, it is only a movie. There's a lot of this self-referential stuff in Bande à Part - canny commentaries in voiceover, a minute of totally absent soundtrack when the characters ask for a minute's silence and so on. It's all very knowing, and good fun, but Godard's mask of irony is cracked by the extraordinary Anna Karina, his wife and muse. Two years earlier, the couple had cameos in Agnes Varda's Cléo de 5 à 7, as two-dimensional Mack Sennett-style heroes in a short film within the film. Karina was made up to look like a rag doll, and that is what she looks like here, even without the bleached face and round rosy cheeks. Godard and Karina made eight films together and it's almost always as if Godard wants to make her two-dimensional, or silent at least, because her wide-eyed face is so iconic; she is his Louise Brooks or Lillian Gish. But this very fact makes her a more inherently tragic figure than Godard seems to have planned. No matter how ironic and artificial the script, there's a lovely sadness in the corners of Karina's eyes, which makes many of the films they did together more hers than his.

Gaby Wood, The Observer, 24 June 2001

BANDE À PART, shot in 25 days and based on the pulp novel “Fool’s Gold” by Dolores Hitchins, was project that Godard embarked on to support his marriage with Anna Karina. The pair hadn’t worked together since Vivre sa vie. Godard called his production company “Anouchka”, his pet name for Karina, and he gave the character she played Odile, after his late mother. At an English language school in Paris, two petty swindlers, Franz (Frey) and Arthur (Brasseur) fall in love with Odile (Karina). Arthur lives with the enigmatic Madame Victoria (Colpeyn) in the suburbs, where a mostly absent Mr. Stolz has a huge amount of cash hidden in his cupboard. Franz and Arthur want nothing more than to bed with Odile – apart from stealing the money. Their clumsy plan backfires, they kill Madame Victoria, and while Franz and Odile escape to South America to start a new life, Arthur and his uncle kill each other in Madame Victoria’s garden before the money, now hidden in a dog’s kennel, is stolen by surprise. Godard had run out of producers and had asked Columbia, Paramount and UA to give him 100.000 $ to make a picture. All questioned the high figure Godard was asking for and when he explained that this was for the whole production, only Columbia agreed to take him up on the project. Godard gave them a choice of three topics: the first about a woman leftie, the second about a writer and the final topic about the Hitchins crime novel: they obviously picked the latter. With such a small budget,, the studio did not even bother about a script. The director’s poetic voice-over re-tells the story from the emotional point of view of the three main protagonists, in a narrative full of quotations, references and in-jokes. But instead of being all-knowing, the voice-over soon loses the plot – the characters are coming into their own. It gives the impression that Godard was filming in perpetual motion. Everything and everybody moves in silence: in a scene at the ‘Café Madison’, there is no sound for a minute, followed by the now famous dance scene of the trio, a polonaise copied by many, amongst them Hal Hartley and Quentin Tarantino. The film is symbolised by the three of them racing through the Louvre. The images are rush by: money, pistols, death, Odile’s stockings as masks, Shakespeare and always the leafless trees, set against a dark November sky. Raoul Coutard’s images literally shot on the run, like he had done during the Indochina war. Again, Godard was in opposition to everything – even though the film turned out to be very much a neo-classical in style: “This movie was made as a reaction against anything that wasn’t done. It was almost pathological and systematic. A wide-angle lens is not normally used for close-ups? Then let’s use it. A handheld camera isn’t normally used for tracking shots? Then let’s try it. It went along with my desire to show that nothing was off limits.” For once, film and reality coincided: during the shooting, Karina and Godard got back together again, moving into a new apartment in the Latin Quarter, Karina admitting “It’s true: the film saved my life. I had no more desire to live. I was doing very, very badly. This film saved my life”. Watching Bande À Part the for the first time in 1965, as first year students – we all admired the sequences when the actors read colportage stories from newspapers – we thought that it was very cool. According to Raoul Coutard “there was no real script. Jean-Luc would show up with whatever he had written for the day. We’ve end up filming that. If he hadn’t written anything, we would not have filmed anything.” The newspaper stories, as it turned out, were just paddings, when the master had not written enough.

Filmuforia, from the programme for GODARD SEASON AT THE BFI FROM JANUARY – MARCH 2016

What you thought about Bande à Part

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 (17%) | 35 (47%) | 13 (17%) | 6 (8%) | 8 (11%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 75 Film Score (0-5): 3.52 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

136 members and guests attended the screening of Bande à Part and the short film ACE on March 27th. 75 responses were received in total, 5 by e mail, this represents a hit rate 55%. You were divided in your reviews of Bande à Part but very enthusiastic about ACE with the following reflecting those thoughts… “I really enjoyed ACE – good fun”. “Excellent short. Brilliant baffling main feature”. “The short was brilliant. Worth coming just for that! I loved the movie visually – couldn’t call it b/w as there were so many shades of grey too. Rather pretentious …” As I said in my introduction to this screening “In the 2011/12 season, we showed Godard’s first feature film Breathless. John Taylor (my predecessor) wrote at the time “Responses from members divided roughly into three categories: those who considered the film retained intrinsic power and quality; those who recognised its quality but saw it largely of its time and superseded by better, more modern films and those who found few merits in it; whatever its social and historical context and of little appeal today”. That statement still holds true, based on what I have read. The following offers a good summary of what is reflected in other comments. “Tricky beast Godard: some good (Breathless, Alphaville, Weekend) some dreadful. I have a theory that those who immerse themselves too deeply in fiction, whether films or novels, are a long time learning that real life doesn’t work that way. This film seems to give the lie to that idea: the characters seem to be creating their own reality as the story unfolds as if in a lucid dream. The plot thus follows a curiously serpentine path as the film seems undecided over what it wants to be and the tone lurches from comedy to romance and violence, seemingly at the whim of the characters themselves. Odd but amusing, an interesting comparison to the self-consciously madcap inventions of Swinging London: ‘Alfie’, The Knack’, ‘Blow up’, etc.” Other comments are below and all are on the website. “Nothing special”. “Very 60’s and so now seems very dated”. “How films have improved! Quite amusing but slow. Do we have to have all these old films?” “Rambling nonsense”. “From Fantasy to incompetent reality – if there had been an interval I would have left!” “Hard going”. “Totally ridiculous”. “Pretentious self-indulgence”. “Couldn’t possibly have been made by anyone else. Took me back to University film club – we loved the non-narrative sardonic voiceover – but we were younger and more chaotic ourselves then”. “Really good”. “What a strange fruit! So very French in many ways. Glib knock off lines. Very amusing. Loved that car!” “This film was probably “cool” once, but hasn’t stood the test of time. The dance, however was crazy cool. The film was just crazy!” “Trés Amusant c’est tout”. “What great fun – what larks”? “Well yes, all those good things that we were told to look for and very entertaining to boot”. “Ultimately quite silly – but having fun with the conventions and with touches of tragedy and comic elements”. “Totally implausible – but utterly entertaining. B/W much more suitable than colour, in this case”. “What a great film. Such Fun!!” “Dreadful sound – the one minute silence was terrific!” “Thoroughly enjoyable, but clearly not to be taken seriously- hugely of its time – 60’s mores- a piece of history. Decent bright picture and legible subtitles though in spite of its age”. “Not much plot, well-acted. The dancing was good”. “Very French! Loved 60’s Paris and the narrator. Pre Amelie-esque?” “I enjoyed it – but really don’t know what more to say!” “All the worlds a stage” “Very stylish. Stood the test of time well. Very influential”. “A difficult film to comment on”. “Bizarre. An enjoyable spoof and one that will be remembered. Did it inspire the Goodies?” “Funny, mad, of its time. Music great and also the dancing”. “Although a strange scenario I enjoyed this film. I enjoyed the humour”. “Strange but very good – enjoyed the driving, the dancing and the running through the Louvre”. “Trés Amusant”. “A bizarre mix of comedy, light entertainment ad pathos…but somewhat enjoyable!” “Quite the most weird film I have ever seen…but very satisfying. Calming and in the end enjoyable”. “Weird”. “Shades of Butch Cassidy. Short was fun”. “Good – a bit like la Grande Bouche?” “Slow bit rather charming in a 1960’s way. Subtitles very good on the b/w screen. I remember the music of that era well”. “I am still trying to work out what was the beginning, the middle and the end. But there were some very enjoyable scenes. Loved the soundtrack”. “I can’t say if it was good or bad. But I do say I did not enjoy it”. Described as “from another planet” and “I don’t know what films the British film industry were making in 1964 but I bet an awful lot of France’s films there were not like that! Fascinating”. “I can’t see a good reason for selecting this film for an intelligent group. Please do better”. “Dull and unrealistic”. “What a load of pretentious nonsense!! I wish I’d slept for longer. Best bit was the dog at the end on the ship!! This season’s films have been awful”. “The car is the star”. “Just so Goddard! Certainly original with humouress moments to towards the end. A crazy farce that only he could dream up”. “Might have seemed cool in 1964, but a few amusing sequences apart it now just seems self-indulgent”. “Quite barmy and very noisy and a bit boring”. “I'm still thinking about Bande a Part. I do generally like 'off the wall' films and I did like this one, but it left me feeling a bit empty. Perhaps I've not seen enough of the American pulp movies to get the references, though many of the scenes were quite evocative and gently poking fun at these film styles. If it was meant to be something of a spoof on American pulp movies, it didn't work very well for me at least. Take the 'twist' at the end. So Victoria didn't die although pronounced not breathing and looking very dead. Stoltz turned up for no apparent reason. If it was supposed to have been a set-up, what was the object of it? If not, what were they up to? I do get it in terms of film sequences, but the lack of a link or connection to this scene undermined the value of the spoof. Or perhaps I missed something”. “Good plot, fully-rounded characters and beautifully filmed and edited. Great dance scene and an ultra-cool and very French feel to the whole thing. Very witty in parts e.g. the English teacher translating Shakespeare so frenetically on the fly - very funny. I disagree with the reviewer Pauline Kael who said that 'the crime does not fit the daydreamers or their milieu’ - once you meet the violent uncle and see the lengths he is eventually willing to go, we understand that a robbery would not be a step too far for Arthur”. “While at times I had to stifle yawns, overall I enjoyed the film. It rather reminded me of La Strada with the innocent/simple girl, bullying man and the wonder as to what on earth inspired the director to make the film the way they did. After finding the endings of the last two films screened rather unsatisfactory, at least this one was clear! Enjoyed the dancing and race through the Louvre. Didn't enjoy the background noise throughout the soundtrack, highlighted by the short but enjoyable minute's silence in the café”. “Enjoyed this quirky film as it intertwined real, unreal to surreal often leaving me unsure of what I was watching! I felt sure in the final shoot out that Artur had put blanks in his uncle's gun…hence the dramatic staggering death scene but I was wrong and real life happened....or did it? I don't know!”