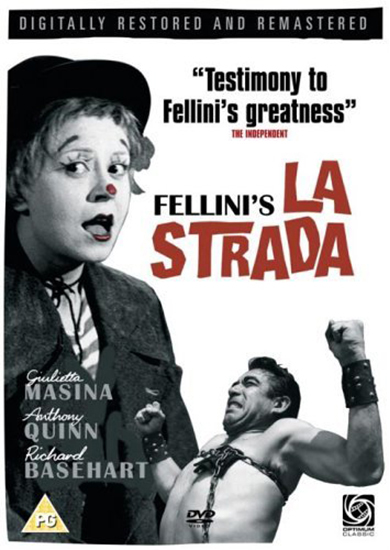

La Strada

Could be considered Fellini's first masterpiece with a story of hope in the poverty of post-war Italy. A waif is sold to a brutish travelling entertainer (Anthony Quinn), consequently enduring physical and emotional pain along the way. Won Best Foreign Language Film Oscar in 1957.

Film Notes

A low-key mood study about a broken-down carnival strongman and his half-wit assistant traveling through the bleak backwaters of post-war Italy wouldn’t, at first glance, appear to have much going for it in the way of international critical and commercial appeal. But from the moment of its release in 1954, it was clear that La strada had everything. An immediate box office hit, La strada won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. In Italy it catapulted its director, Federico Fellini, to the front ranks of that country’s greatest filmmaking talents. It revived the acting fortunes of its American star Anthony Quinn, and made his co-star, Giulietta Masina, a world-wide sensation. Nino Rota’s haunting musical theme for La strada poured from countless radios, juke boxes and record players. But far more important than these particulars of first rank success was the simple fact that this uniquely bittersweet comedy-drama touched people’s hearts in a way few films have managed to do. And, there is no question that it will continue to do so for years to come. Federico Fellini began his career working with a traveling theater troupe before becoming (in succession) a radio gag writer, a cartoonist, a scriptwriter and assistant for such established Italian talents as Roberto Rossellini and Pietro Germi. His first features, The White Sheik (1952) and I Vitelloni (1953) suggested he was aiming to establish himself as a comic filmmaker. La strada consequently came as a surprise. The “neo-realist” school of filmmaking (Rossellini’s Open City and DeSica’s Bicycle Thieves) had accustomed critics and audiences to dealing with the darker and more depressed areas of the post-war Italian scene, but La strada was different. These characters are certainly recognizable as human flotsam and jetsam, but no one would call them “ordinary.” Marginal in the extreme, they wind their way across a landscape so barren as to resemble one of De Chirico’s eerily surrealistic canvases. Likewise, Fellini’s treatment of their adventures and interactions doesn’t aim for a sense of commonality on the level usually associated with naturalism. There’s an odd touch of fantasy hanging about this childlike waif and the sullen brute who keeps her, and more than a touch of the magical to the circus high-wire walker known as The Fool, who they meet along the way. It is clear that Gelsomina (Giulietta Masina) is mentally retarded. It is also clear that this mental state hasn’t destroyed her sense of self. Zampano (Anthony Quinn) may have bought her from her mother like a common slave, but it is Gelsomina who comes to understand the world and her place in it, not her brutish keeper. “Why do you want me?” Gelsomina asks Zampano —she’s not pretty, she’s not talented and he clearly doesn’t love her. But it is also clear that a man even on as low a level of the totem pole as Zampano needs something he can call his own—and that something is Gelsomina. The Fool (Richard Basehart) helps Gelsomina come to grips with this fact, and her place in the world as well. A catalyst in other characters’ lives, he gives Gelsomina hope. But his merciless teasing of the humorless Zampano precipitates the disaster that brings La strada to its tragic climax. Fellini’s treatment of all of this is effortless and elegant. These particular characters may carry universal weight, but they’re never allowed to degenerate into cardboard symbols. Giulietta Masina’s clown-like face and comic timing inevitably recall Chaplin. But neither the actress nor her director press the point. La strada never presses any point. Like the characters’ realizations about themselves and the world, the meaning of La strada slips over you gradually, simply,unforgettably.

David Ehrenstein, The Criterion Collection, March 07, 1988

It is 16 years since Federico Fellini’s 1954 masterpiece La Strada was last rereleased in British cinemas and now is another chance to be blown away by this film’s power, its simplicity, its humanity, its theatricality, its heart-wrenching operatic pathos. The crowd scenes are extraordinary: simply, the faces Fellini finds to put on screen, children and animals coming serendipitously into shot. Guilietta Masina gives an artlessly Chaplinesque performance as Gelsomina, the elder daughter of a poor family – simple, solemn, bordering on what might today be called learning difficulties – who is sold by her mother for 10,000 lire to a lumbering, hatchet-faced strolling player called Zampanò, unforgettably played by Anthony Quinn. He intends to train her as his assistant for his cheesy “strongman” act, taking to the road, sleeping in his rackety caretta motorbike-van, travelling through scrublands and waste grounds of postwar Italy and doing their routine in town squares. Apparently, Gelsomina’s sister Rosa used to work with Zampanò, but she has died in circumstances never made entirely clear. Fellini allows this buried tragedy to fester under every succeeding minute of the movie. The thuggish Zampanò abuses poor Gelsomina like a child he hates and she poignantly accepts her fate. Kindly, innocent nuns allow them to stay overnight in a convent, where Zampanò bullies Gelsomina into helping him steal some silver. The nuns had told her that they have to keep moving from convent to convent so they don’t form an attachment to worldly things, and poor Gelsomina’s face had lit up, having glimpsed a state of grace in her own poverty and endless travel. They then briefly work in a circus, where they fatefully encounter a cheeky Fool (Richard Baseheart) who is to change their lives. At one stage, the Fool tries to coach Gelsomina in a simple comedy routine: he will play a sentimental tune on the violin and she will come up behind him and undercut him with a silly parp on the trombone. Fellini is doing the reverse: he creeps up behind the vulgar trombone honk of ordinary life and plays a heartrending tune on the violin. Masina is mesmeric and the final scene, with Quinn’s Zampanò briefly gazing up at the sky, is mysterious and unbearably moving.

Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian, 17th May 2017.

Federico Fellini's "La Strada" (1954) tells a fable that is simple by his later standards, but contains many of the obsessive visual trademarks that he would return to again and again: the circus, and parades, and a figure suspended between earth and sky, and one woman who is a waif and another who is a carnal monster, and of course the seashore. Like a painter with a few favorite themes, Fellini would rework these images until the end of his life. The movie is the bridge between the postwar Italian neorealism which shaped Fellini, and the fanciful autobiographical extravaganzas which followed. It is fashionable to call it his best work - to see the rest of his career as a long slide into self-indulgence. I don't see it that way. I think "La Strada" is part of a process of discovery that led to the masterpieces "La Dolce Vita" (1960), "8 1/2" (1963) and "Amarcord" (1974), and to the bewitching films he made in between, like "Juliet of the Spirits" (1965) and "Fellini's Roma" (1972). "La Strada" is the first film that can be called entirely "Felliniesque." It is being re-released, in a restored print presented by Martin Scorsese, at a poignant moment: Fellini received an honorary Oscar at the 1993 Academy Awards, with his wife Giulietta Masina applauding tearfully in the front row. Since then, both have died. The story is one of the most familiar in cinema. A brutish strongman named Zampano (Anthony Quinn) tours Italy, living in a ramshackle caravan pulled by a motorcycle. He needs an assistant for his act, and from a poor widow at the seaside he purchases her slow-witted daughter Gelsomina (Giulietta Masina). He is cruel to the young woman, but she has a Chaplinesque innocence that somehow shields her from the worst of life, and she is proud of his accomplishments, such as learning to play his signature tune on a trumpet. In a provincial town, Gelsomina is struck breathless by the Fool, a high-wire artist who works high above the city street. Zampano signs up with an itinerant circus, where the Fool (Richard Basehart) is employed. He mocks Zampano, who attacks him in a rage, and is jailed. The Fool is attracted to Gelsomina, but sees that she has formed a strong bond with the strongman, and leaves so they can be together. But Zampano's jealousy and rage return; he kills the Fool; Gelsomina goes mad, and all is in place for one of Fellini's favorite endings, in which a defeated man turns to the sea, which has no answers. Seeing the film again after several years, I found myself struck first of all by new ideas about the Fool. The film intends us to take him as a free and cheerful spirit (the embodiment of Mind, Pauline Kael tells us, with Zampano as Body and Gelsomina as Soul). But he has a mean, sarcastic streak I had not really registered before, and his taunting of the dim Zampano is sadistic. To some degree he is responsible for his own end. Masina's character is perfectly suited to her round clown's face and wide, innocent eyes; in one way or another, in "Juliet of the Spirits," "Ginger and Fred" and most of her other films, she was always playing Gelsomina. Her performance is inspired by the silent clowns (I was reminded of Harry Langdon in "The Strong Man"), and is probably a shade too conscious and knowing to be consistent with Gelsomina's retardation. The character should never be aware of the effect she has, but we sometimes feel Gelsomina's innocence is calculated. It is Quinn's performance that holds up best, because it is the simplest. Zampano is not much more intelligent than Gelsomina. Life has made him a brute and an outcast, with one dumb trick (breaking a chain by expanding his chest muscles), and a memorized line of patter that was perhaps supplied to him by a circus owner years before. His tragedy is that he loves Gelsomina and does not know it, and that is the central tragedy for many of Fellini's characters: They are always turning away from the warmth and safety of those who understand them, to seek restlessly in the barren world. In almost all of Fellini's films, you will find the figure of a man caught between earth and sky. ("La Dolce Vita" opens with a statue of Jesus suspended from a helicopter; Marcello Mastroianni opens "8 1/2" floating in the sky, tethered to earth.) They are torn between the carnal and the spiritual. You will also find the waifs and virgins and good wives, contrasted with prostitutes and temptresses (Fellini in his childhood encountered a vast, buxom woman who lived in a shack at the beach, and made her a character again and again). You will find journeys, processions, parades, clowns, freaks, and the shabby melancholy of an empty field at dawn, after the circus has left. (Fellini's very last film seen in this country, 1987's "Intervista," ends with such an image.) And you will hear it all tied together with the music of Nino Rota, who, starting with "I Vitelloni" in 1953, faithfully composed for Fellini some of the most distinctive film scores ever written, merging circus music and pop songs with the sadly lyrical sounds of accordions and saxophones and lonely trumpets (the tune ending in a rude trumpet squawk, which Zampano teaches to Gelsomina, is mirrored in the nightclub scene in "La Dolce Vita"). When Fellini died, the critic Stanley Kauffmann wrote an appreciation in The New Republic that ended with the words: "During his lifetime, many fine filmmakers blessed us with their art, but he was the only one who made us feel that each of his films, whatever its merits, was a present from a friend." In the words of a film about him, "Ciao, Federico."

Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun Times, April 1, 1994.

What you thought about La Strada

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 (29%) | 24 (47%) | 11 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 51 Film Score (0-5): 4.02 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

97 members and guests attended our screening of Fellini’s La Strada. 53% of you providing a response to the film which was very mixed with comments ranging from “If GFS only screened one film of this quality every season, it would be worth the annual subscription and “It left me speechless. The most amazing film I’ve ever seen”. to “Boring and unpleasant”. One correspondent wrote “I left the film unimpressed and disappointed...I "slept on it" in case something fundamental was revealed to me...I re-read the "professional" reviews...but no, I found the film underwhelming and unconvincing, and the acting substandard. How this film made Fellini an "auteur" and a "sensation" of Giulietta Masina is completely lost on me. (And it had nothing to do with film age/language/b&w - I thought "M" was a far better film). But each to his own. At least I have ticked it off the "list of films to see"”. Another wrote, “A good film. Only Fellini could make this sad story into a uniquely cinematic experience – a classic”. We also had, “Not the most accessible film nor one it is easy to see what its making was inspired by. Having said that, the relationship between the brutish man and simple, innocent girl was quite compelling. Better sub titles!” Martin Scorsese was heavily influenced by all of Fellini’s body of work and there are numerous interviews with him on the internet. He describes La Strada as a journey on the road of life; that it is sheer poetry, exuding warmth and power, reflecting the darkness that can overcome the soul and unexpressed love. OK those are some of his thoughts; you said that it was “of its time but still brilliant” and that it was “a beautiful film – sad, poignant. The pathetic character played by female lead Giulietta Masina as Gelsomina was brilliant – so expressive”. Others told us that “I never used to understand Fellini, nothing’s changed” and that it was “very depressing. Beautiful, haunting music. Very well-acted but too slow and two long- not one that I enjoyed!” “If that’s a classic I need to be educated”. “How very depressing! Excellent acting by Anthony Quinn. Not sure about Masina’s quasi Chaplinesque approach though. Too long and rather dated”. “No empathy with the characters but an interesting film”. “Strong performances from both leads, but overall showed its age. A bit stilted”. These observations were countered by the following extracts “Most enjoyable. Wonderful depiction of Italian post war poverty. Anthony Quin was fabulous”. “A sad film – full of hope- but no happy ending – unless you think “at last he learnt to cry””. “Very subtle and deceptively simple. An increasing depth as the film unfolded”. “Very moving and the acting was superb. Tension built up to such sadness”. “So poignant. Amazing acting”. “Excellent acting, especially from Quinn. I loved Giulietta Masina’s expressive face. Very unpredictable plot – more a series of incidents. A tragic figure”. “Film colour – black and white often too pale so facial expressions were missed. What a sad tragi/comedy! However I was pleased to see it”. “Too miserable”. “Well staged and brilliantly acted by the two leads; unique in its way”. “Very enjoyable but I still had trouble with the sub titles”. “Still strange and engaging after all these years. One that HAS stood the test of time”. “A different age”. “Not like Godalming”. “Please can we have some heating”. “Wonderful acting”. “The fool is hurt”. “Amazing acting but very depressing”. “Really well remastered. Brilliant performances” “Doubtful”.