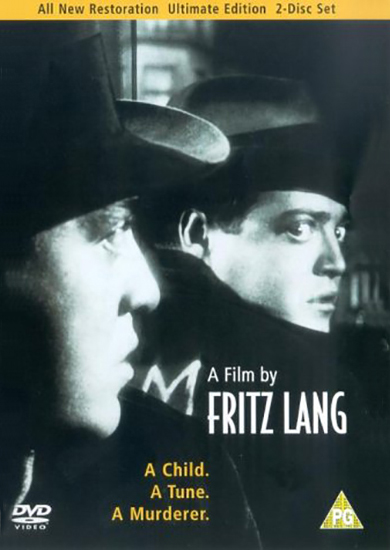

M

M is about a terrorized city, and a plump little man with wide eyes who is a pathological child-killer, unable to control his urge for killing. In an unforgettable performance by Peter Lorre, directed by Fritz Lang, this black/white classic is a psychological thriller considered a landmark in the story of suspense movies.

What's this?

Film Notes

Based on the fiendish killings which spread terror among the inhabitants of Düsseldorf in 1929, there is at the Mayfair a German-language pictorial drama with captions in English bearing the succinct title "M," which, of course, stands for murder. It was produced in 1931 by Fritz Lang and, as a strong cinematic work with, remarkably fine acting, it is extraordinarily effective, but its narrative, which is concerned with a vague conception of the activities of a demented stayer and his final capture, is shocking and morbid. Yet Mr. Lang has left to the spectator's imagination the actual commission of the crimes. Peter Lorre portrays the Murderer in a most convincing manner. The Murderer is a repellent spectacle, a pudgy-faced, pop-eyed individual, who slouches along the pavements and has a Jekyll-and-Hyde nature. Little girls are his victims. The instant he lays eyes on a child homeward bound from school, he tempts her by buying her a toy balloon or a ball. This thought is quite sufficient to make even the clever direction and performances in the film more horrible than anything else that has so far come to the screen. Why so much fervor and intelligent work was concentrated on such a revolting idea is surprising. It is unfurled in a way that reveals Mr. Lang and Thea von Harbou, his wife, evidently studied what happened in Düsseldorf during the score of atrocious murders, which incidentally caused young women to go about armed with pepper in case they were picked out by the slayer as possible victims. In the film the Commissioner of Police gives all his attention to trying to track the murderer down. He goes about his work in a systematic fashion, but when another crime is perpetrated he is talked to heatedly over the telephone by his superior. So far as the film spectator is concerned, there is no mystery concerning the criminal. He is perceived looking into a mirror, making grimaces at himself, and later dawdling along the street, looking into shop windows. He has a habit of whistling a few bars of a tune, and apparently it is something he has little control over, for this whistling is actually responsible for his capture. Mr. Lang has the adroit idea of having thugs, pickpockets, burglars and highwaymen eventually setting about to apprehend the Murderer. His crimes are making things too hot for them and, bad as they are, they are depicted as being almost sympathetic characters compared to the Murderer. Every criminal in the town is told by the chief crook to be on the lookout for anybody who looks suspicious. Beggars and peddlers, as well as the thieves and swindlers, are all eager to catch the Murderer. It is not astonishing that anybody doing a kindly turn for a child is suspected of being the criminal. A harmless individual is almost mobbed by hysterical women and enraged men. Meanwhile the Murderer is at large and has boastfully written of his last crime to the newspapers. The letter is analyzed. It was written evidently on a rough wooden table, and the sleuths draw circles about the map of the town as they widen their search. But his capture does not come about through the minions of the law. It is a blind man, a peddler of toy balloons, who gives the alarm. He had sold a balloon a few days before to the man who had whistled the notes of an operatic tune. Suddenly the blind man several days later hears the melody whistled again, and it dawns upon him in a few seconds that the Murderer is passing. He gives the alarm, and in the course of the chase a youth, who had marked in chalk the letter "M" on his hand, slaps the suspect on the back. There is a wild chase, the crooks being eager to get their man. They are willing to risk being held for crimes, and when the Police Commissioner understands from a prisoner that he and others were following the Murderer, the official is so stunned that he lets the cigar he is smoking drop from his mouth. One perceives the panting Murderer trying to get the lock off a door, his eyes wilder than ever, and perspiration dripping from his forehead. But the frantic, shrieking man is finally captured by the thieves, and a most interesting series of scenes is devoted to his trial. He bleats that he is a murderer against his will, whereas those before him commit crime because they want to. A thief presides at the trial. The Murderer has counsel, who says that the Murderer needs a doctor more than punishment. Then the Murdered is handed over to the police and a mother of one of the fiend's little victims declares that the death of the man will not give her back her child. It is regrettable that such a wealth of talent and imaginative direction was not put into some other story, for the actions of this Murderer, even though they are left to the imagination are too hideous to contemplate.

M.H. The New York Times, April 3, 1933

M is for Murder, or Mörder, the chalked letter pressed on the shoulder of a notorious child-killer in Berlin by a member of an organised criminal underground – a secret sign to identify the psychopath and kill him. This is so that the police can call off their own city-wide manhunt, which is seriously inconveniencing the criminal classes. Fritz Lang's 1931 movie is back on re-release and Peter Lorre plays the porcine, pop-eyed serial killer Hans Beckert, speaking German with a rasping, querulous shout – rather different to the unmistakable nasal, lugubrious English of his later Hollywood career. Otto Wernicke plays pudgy police inspector Lohmann, and Gustaf Gründgens is Schränker, the crime overlord who will finally sit in judgment on Beckert, presiding over something between a kangaroo court and a revolutionary tribunal. Lang depicts the paranoia and feverish atmosphere that gives birth to the dual investigation from the cops and the criminals. Lohmann has a determined, forensic technique, analysing the handwriting on Beckert's jeering letter to the press, and the woodgrain of the table the paper appears to have pressed on. Meanwhile, a hidden army of crooks and thieves pass on their own tips, and a blind peddler crucially recognises the tune Beckert whistles. It is a cousin to the early Hitchcock of The Lodger, and I have always found something even something faintly Ealingesque about its cynicism and satire. What is fascinating is how Lang fetishises smoking: everyone has huge cigars, bulbous pipes and cigarettes in holders. It is as if smoke is the endless industrial byproduct of the city's folly, greed and shame.

Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian, September 4th 2014

The horror of the faces: That is the overwhelming image that remains from a recent viewing of the restored version of “M,” Fritz Lang's famous 1931 film about a child murderer in Germany. In my memory it was a film that centered on the killer, the creepy little Franz Becker, played by Peter Lorre. But Becker has relatively limited screen time, and only one consequential speech--although it's a haunting one. Most of the film is devoted to the search for Becker, by both the police and the underworld, and many of these scenes are played in closeup. In searching for words to describe the faces of the actors, I fall hopelessly upon “piglike.” What was Lang up to? He was a famous director, his silent films like "Metropolis” worldwide successes. He lived in a Berlin where the left-wing plays of Bertolt Brecht coexisted with the decadent milieu re-created in movies like "Cabaret.” By 1931, the Nazi Party was on the march in Germany, although not yet in full control. His own wife would later become a party member. He made a film that has been credited with forming two genres: the serial killer movie and the police procedural. And he filled it with grotesques. Was there something beneath the surface, some visceral feeling about his society that this story allowed him to express? When you watch "M,” you see a hatred for the Germany of the early 1930s that is visible and palpable. Apart from a few perfunctory shots of everyday bourgeoisie life (such as the pathetic scene of the mother waiting for her little girl to return from school), the entire movie consists of men seen in shadows, in smokefilled dens, in disgusting dives, in conspiratorial conferences. And the faces of these men are cruel caricatures: Fleshy, twisted, beetle-browed, dark-jowled, out of proportion. One is reminded of the stark faces of the accusing judges in Dreyer's “Joan of Arc,” but they are more forbidding than ugly. What I sense is that Lang hated the people around him, hated Nazism, and hated Germany for permitting it. His next film, "The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” (1933), had villains who were unmistakably Nazis. It was banned by the censors, but Joseph Goebbels, so the story goes, offered Lang control of the nation's film industry if he would come on board with the Nazis. He fled, he claimed, on a midnight train -- although Patrick McGilligan's new book,Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast, is dubious about many of Lang's grandiose claims. Certainly "M” is a portrait of a diseased society, one that seems even more decadent than the other portraits of Berlin in the 1930s; its characters have no virtues and lack even attractive vices. In other stories of the time we see nightclubs, champagne, sex and perversion. When "M” visits a bar, it is to show closeups of greasy sausages, spilled beer, rotten cheese and stale cigar butts. The film's story was inspired by the career of a serial killer in Dusseldorf. In "M,” Franz Becker preys on children -- offering them candy and friendship, and then killing them. The murders are all offscreen, and Lang suggests the first one with a classic montage including the little victim's empty dinner plate, her mother calling frantically down an empty spiral staircase, and her balloon--bought for her by the killer--caught in electric wires. There is no suspense about the murderer's identity. Early in the film we see Becker looking at himself in a mirror. Peter Lorre at the time was 26, plump, baby-faced, clean-shaven, and as he looks at his reflected image he pulls down the corners of his mouth and tries to make hideous faces, to see in himself the monster others see in him. His presence in the movie is often implied rather than seen; he compulsively whistles the same tune, from "Peer Gynt,” over and over, until the notes stand in for the murders. The city is in turmoil: The killer must be caught. The police put all their men on the case, making life unbearable for the criminal element ("There are more cops on the streets than girls,” a pimp complains). To reduce the heat, the city's criminals team up to find the killer, and as Lang intercuts between two summit conferences -- the cops and the criminals -- we are struck by how similar the two groups are, visually. Both sit around tables in gloomy rooms, smoking so voluminously that at times their very faces are invisible. In their fat fingers their cigars look fecal. (As the criminals agree that murdering children violates their code, I was reminded of the summit on drugs in "The Godfather.”) "M” was Lang's first sound picture, and he was wise to use dialogue so sparingly. Many early talkies felt they had to talk all the time, but Lang allows his camera to prowl through the streets and dives, providing a rat's-eye view. One of the film's most spectacular shots is utterly silent, as the captured killer is dragged into a basement to be confronted by the city's assembled criminals, and the camera shows their faces: hard, cold, closed, implacable. It is at this inquisition that Lorre delivers his famous speech in defense, or explanation. Sweating with terror, his face a fright mask, he cries out: "I can't help myself! I haven't any control over this evil thing that's inside of me! The fire, the voices, the torment!” He tries to describe how the compulsion follows him through the streets, and ends: "Who knows what it's like to be me?” This is always said to be Lorre's first screen performance, although McGilligan establishes that it was his third. It was certainly the performance that fixed his image forever, during a long Hollywood career in which he became one of Warner Bros.' most famous character actors ("Casablanca,” "The Maltese Falcon,” "The Mask of Dimitrios”). He was also a comedian and a song-and-dance man, and although you can see him opposite Fred Astaire in "Silk Stockings” (1957), it was as a psychopath that he supported himself. He died in 1964. Fritz Lang (1890-1976) became, in America, a famous director of film noir. His credits include "You Only Live Once” (1937, based on the Bonnie and Clyde story), Graham Greene's "Ministry of Fear” (1944), "The Big Heat” (1953, with Lee Marvin hurling hot coffee in Gloria Grahame's face) and "While the City Sleeps” (1956, another story about a manhunt). He was often accused of sadism toward his actors; he had Lorre thrown down the stairs into the criminal lair a dozen times, and Peter Bogdanovich describes a scene in Lang's "Western Union” where Randolph Scott tries to burn the ropes off his bound wrists. John Ford, watching the movie, said, "Those are Randy's wrists, that is real rope, that is a real fire.” For years "M” was available only in scratchy, dim prints. Even my earlier laserdisc is only marginally watchable. This new version, restored by the Munich Film Archive, is not only better to look at but easier to follow, since more of the German dialogue has been subtitled. (Lorre also recorded a soundtrack in English, which should be made available as an option on the eventual laserdisc and DVD versions.) Watching the new print of "M,” I found the film more powerful than I remembered, because I was not watching it through a haze of disintegration. And what a haunting film it is. The film doesn't ask for sympathy for the killer Franz Becker, but it asks for understanding: As he says in his own defense, he cannot escape or control the evil compulsions that overtake him. Elsewhere in the film, an innocent old man, suspected of being the killer, is attacked by a mob that forms on the spot. Each of the mob members was presumably capable of telling right from wrong and controlling his actions (as Becker was not), and yet as a mob they moved with the same compulsion to kill. There is a message there somewhere. Not "somewhere,” really, but right up front, where it's a wonder it escaped the attention of the Nazi censors.

Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun Times, August 3, 1997

What you thought about M

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 (38%) | 34 (47%) | 9 (12%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 73 Film Score (0-5): 4.21 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

123 members and guests came to the showing of M and delivered a 60% response with many commenting on the performances and the story line in particular. The following are typical. “Slow start but the pace picked up. What a performance by Peter Lorre – unforgettable”. “Stunning performance by Peter Lorre”. “An excellent film. Acting superb”. “Excellent acting - loved the end”. “Absorbing and well-acted. A powerful comment on German social life in its time”. “I thought this was an excellent film lovingly pieced back together like an old Greek urn but well worth the effort. Peter Lorre's performance was totally believable and the threads in the film of mob violence, scapegoating and the appropriate justice for such awful crimes are all still relevant today”. Others pointed to the age of the film (it was released in 1931, 86 years ago) and said “Although showing its age in places with a few clunky sections, this film was also frequently captivating, and the riveting "kangaroo court" finale was especially compelling. Peter Lorre was superb and utterly convincing. The film raises some challenging moral questions and it is rather disheartening that nearly 90 years later society still grapples with similar issues: The mob mentality whipping up hysteria to accuse and attack the innocent; what to do with murderers claiming insanity....” “Obviously watching the film and reading the subtitles was difficult – but still worth the effort. Lorre was merely good until the final scene – then he was superb. Difficult to believe the age of the film – way ahead of its time – could be remade today – but probably with less impact!” “Some actors reminiscent of the silent movies – not long before”. “Still a powerful film. Amazing for its time”. “A film way before its time. Superb performance from Peter Lorre. The kangaroo court scenes were particularly effective.” “Some elements of a silent film. Some interesting shots e.g. everyone looking off camera to the speaker. Unanticipated ending – abrupt”. “Reminded me of the Keystone cops in parts”. “Exaggerated physicality of the acting shows how soon after silent films this was made”. Several of you had seen the film when in their teens and twenties and commented as follows: “As good as I remember 40 years ago. Peter Lorre’s last section – marvellous and believable”. “Brilliant film. I must have seen it about 40 years ago – and got more out of it this time knowing about the times it was set. Very clever filmmaking – many more contemporary films/directors influenced”. “Better than I remember”. “Well made once it got going”. “I was greatly looking forward to this as I’ve somehow never seen it despite it being a staple of the fleapit independent cinemas of my twenties. There is good reason for its continued popularity as it is the model in many respects for the serial killer hunt series that crowd our screens today, though done with a lightness of touch that allows humour throughout while never losing the menace of the potential destruction of another innocent, a trick those TV series could learn much from… (This continues on the web + others). Lang seems less interested in Lorre’s killer, a brilliant performance, in which he appears almost a child as aghast at his actions as everyone else, than he is in the men hunting him. These are a series of grotesques stepped from the images of Grosz, Dix and, further back, Hogarth, porcine creatures mired in their own filth. Lang has a marvellous eye, Hitchcock surely owes this film a great deal and the Expressionist cinema to which it is itself indebted. The finale lurches rather suddenly into political didactics and feels crude in comparison to the rest. Is there an explanation?” “Just a bit too long but a very good film with an excellent ending”. “I was gripped from start to finish – so many twists and unexpected turns. I found I was watching the interesting characters and missed reading the subtitles! e.g. the man sharpening the pencil at the end of the spectator desk”. “They don’t make them like this anymore…mores the pity” “Wonderful seeing the major early work of a cinematic master. Some lessons are timeless”. “Very powerful, wonderful acting. Effective use of b/w”. “Brilliant. Verging on the melodramatic – but truly dramatic. Mob behaviour – inhibition by justice-an impossible construct but worth the notice”. “Gripping and moving film (once you got used to the… acting) about a manhunt a complex mora issue”. “Very profound. Hit many nails on the head”. “Held me throuought”. “Amazing acting! Black and White stressed the horror! Language used hints to further horrors in a different context within Nazi Germany”. “Another week of trying to figure out what is going on –subtitles near impossible to read. Tremendous climax to the film – was there justice in the end?” “Riveting last 30 minutes but the 90 minute version would have been more satisfying… less like a farce than a high tension murder mystery”. “This is what happens when people take the “Lorre” into their own hands”. “No music…good use of silence”. “Great final speech from Peter Lorre. Strange section with no sound? A few weird camera shots i.e. Inspector Lohmann in his chair shot from below.. Up?” “Wonderful cinematography – great story and direction. Peter Lorre perfect – amazing eyes!” “An excellent story, well told with lots of lovely side issues i.e. attitude of public to suspects, criminal desire not to be inconveniencing – yes a lovely film”. “Not much has changed at a base level”. “Cleverly done. Unusual presentation. Comic touches”. “An interesting period piece”. “Too long. Great storyline/ending”. “Expected more tension and the vocals were a bit loud. Good to have seen it but wouldn’t want to watch again”. “Interestingly directed with a few fascinating moments but overall found it tedious”. “The acting was very good but the film was very old”. “Very dated and too long but interesting view of pre-war Germany”. “Very disappointing. Not at all what I expected. Almost boring”. “Stolid, heavy handed, and often tedious, with occasional dramatic moments. Some cracking performances but even Lorre didn’t prevent me from occasionally wanting to doze. An interesting vignette of 1930’s Germany”.