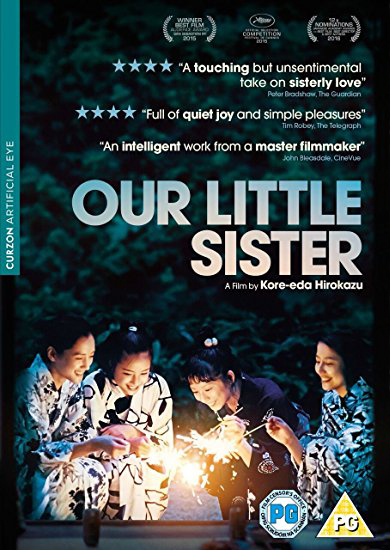

Our Little Sister

Another Koreeda film in which quiet family drama unfolds in contemporary Japan. This is a story that revolves around three sisters who live in their grandmother's home and the arrival of their unknown 13 year old half-sister.

What's this?

Film Notes

‘Accentuate the positive’ hardly begins to sum up the atmosphere in Koreeda Hirokazu’s enchanting new film Our Little Sister (Imimachi Diary), which channels the Japanese master Ozu Yasujiro at the same time as it lovingly recreates the world of Hollywood 1940s family melodramas like Meet Me in St Louis and Little Women. Calling on the audience to travel with it into the warm embrace of its small-town setting, the film richly repays our suspension of cynicism, thanks not a little to Koreeda’s masterly tweaking of the emotional level and the discreet beauty of the cinematography by Takimoto Mikiya (who also shot Like Father, Like Son). Indeed only when Takimoto allows himself a flourish – as in a delirious bicycle ride through a tunnel of cherry blossom or an elegant, Ozu-style deep-focus framing of three sisters chatting in the evening, one on the veranda, one in the doorway, one inside the house – does it become clear how carefully controlled the film’s visuals otherwise are. Our Little Sister doesn’t so much have a plot as string together a series of episodes, reflecting its origin in instalments from Tales from a Seaside Town (the film’s original Japanese title), an ongoing saga published monthly in the Japanese woman’s manga Flowers Magazine. With the barest of expositions – a phone call, a train journey, a funeral – we get to the film’s definitive set-up: four sisters, ranging in age from 29 to 13, live together in a large, slightly rickety family house in the coastal town of Kamakura. At first there are but three. Sachi (Ayase Haruka), the oldest at 29, works at the local hospital, where she is about to be put in charge of the new terminal care facility; Yoshino (Nagasawa Masami), 25, works in a bank, and is promoted in the course of the film from teller to loan manager; Chika (Kaho), at 21 the slightly kooky youngest, works in a shoe store. Sachi is having an unrewarding affair with a married man; Yoshino has a string of temporary lovers; Chika is devoted to her afro-toting boyfriend who used to be a climber but lost four toes on Everest. Their father long ago went off north with another woman; their mother, ashamed, also deserted them, leaving them to be looked after by their grandmother, who has since died – developments that could betoken trauma but are here accepted as the way things are. Only once, when the mother returns for a memorial service, do anger and resentment bubble briefly to the surface. Three sisters become four when their father dies and, on a whim, Sachi invites their teenage half-sister Suzu (Hirose Suzu) to come and live in the family house. The house itself, complete with shrine and plum tree, is a major character, both refuge and relic, protecting the sisters from the world but also holding them back from joining it. There is frequently the hint – there if you want to take it (which the monthly readers of Garden Magazine probably don’t) – that this haven, like childhood, must one day end. But the film’s real appeal lies in its unabashed portrayal of a small-town Arcadia where time is measured by annual events – the cherry blossom, the landing of fresh whitebait in the port, the summer fireworks, the making of plum wine to grandma’s recipe from the old tree in the garden – and there are no problems that family and community cannot solve. “If the gods don’t take care of it, then I guess we’ll have to,” says someone. Even Yoshino’s boss at the bank is more concerned with finding solutions to his clients’ problems than in calling in the loans. And when a family friend and owner of a nearby diner dies (in, of course, Sachi’s hospital), it is important for everyone to know that her cherished recipe for horse mackerel will survive. Our Little Sister avoids the soul-searching of Like Father, Like Son, the home-alone trauma of Nobody Knows and even the ‘so what?’ message of Air Doll, focusing instead on the values of tradition and family, which hold together even when both parents abandon their children – twice, in the case of their father, whom Yoshino forgivingly describes as “lovable but hopeless”. Slightly hampered by an episodic structure deriving from its source, Our Little Sister is nevertheless a seductive and engrossing celebration of family and community. It may prove a little sentimental for some tastes; but, like the plum wine that features repeatedly, the film manages a blend of sweetness and acidity, drawn from a source that will eventually disappear but is richly satisfying for the 128 minutes we get to spend under its spell.

Nick Roddick, Sight & Sound, 1 June 2015.

If you could trust any director to tell a two-hour family story with a bare minimum of dramatic conflict and still make it sing, it’s Hirokazu Kore-eda, Japan’s modern master of domestic observation, who has invested his new film with a tantalisingly Chekhov-like sensibility. Our Little Sister is full of quiet joy and simple pleasures, the taste of fresh whitebait over rice and plum wine steeped lovingly for a decade. Precisely because it’s less emotionally coercive than Kore-eda’s last couple of pictures, it’s even more moving: rather than lunging full-bore for the solar plexus, the truths it’s telling creep up on you. It’s a story about grace, kindness, and a form of rescue: that of 15-year-old Suzu (Suzu Hirose, an absolute pleasure to watch), by the three half-sisters she’s never met until their father’s funeral. Estranged from their dad after he left them for Suzu’s mother, this trio - a nurse called Sachi (Haruka Ayase), louche bank employee Yoshino (Masami Nagasawa) and Chika (Kaho), a goofy soul who works in a sports shop - make the trip to a provincial corner of Japan when he dies. Not only do they meet Suzu for the first time, but also her self-absorbed stepmother, his third wife, whose ability to look after this grieving teenager is tangibly dubious from everything she says and does. “He was both kind and hopeless,” Sachi reflects about their father, who had a habit of overlending money to the point of getting into debt himself, and falling in love with single women out of sympathy. Matching his kindness with a compassionate gesture of their own, she and the others offer to take Suzu into their rambling ancestral home in the small city of Kamakura, an hour from Tokyo. Because their own mother left them at the time of their father’s liaison, Sachi is the de facto head of the family, and squabbles from time to time with the more free-spirited Yoshino, who is rarely without a beer in her hand or a new boyfriend even less stable than the last. By and large, though, Suzu slots into this caring home with close to no friction at all: they have plenty of room for her, all have jobs, and she’s a considerate girl, mature beyond her years, whose main worry is what her mother did to the Koda family by stealing not one but both of their parents away. The sadness of the film - it breaks your heart regularly, and with the softest touch - resides in this theme of stolen childhoods, and the committed efforts of these four young women to help each other survive. There are treats they give and receive, and the film gives us plenty of its own, such as a spirit-reviving cycle ride through a corridor of cherry blossom. There are also gentle ironies in the traits this quartet have inherited from the older generation. Sachi is harshest on their father for his infidelities, but she’s the one dating a married colleague who can’t bring himself to divorce his clinically depressed wife. She’s quick to rise to anger - Ayase, imperious, gorgeous and stern, gives her a brooding maternal anxiety that’s a trifle scary - so it’s a point no one dares raise. Kore-eda wraps us up tight in this clan’s daily lives, season following season, and very carefully weaves his way through, so that none of the film’s developments - Yoshino’s dating woes, Suzu’s first crush - feel like dramatic swerves for the sake of drama. A visit from their mother, played with touching pain and a lot of suppressed guilt by Shinobu Otake, threatens turmoil, and a distressing row erupts when she tactlessly suggests selling the house they’ve all lived in since childhood. But this scene’s played so credibly it’s about the other characters trying to dampen the conflict, rather than a dramatist excitedly stoking the flames. It ends up feeling more like an argument you’ve witnessed in life than one from a movie. All told, the patience of the filmmaking is pretty remarkable, a feat of embroidery slowly taking shape, and it inspires a corresponding faith in the willing viewer - it’s an invitation to sit back and settle in for one of Kore-eda’s loveliest films. The source book, by the way, is a manga called Umimachi Diary, which you may want to go out and devour as soon as it’s over, almost as a way of staying in touch. It’s quite a wrench saying goodbye to this lot.

Tim Robey, The Telegraph, 20 May 2015

This sweetly tender movie from Japanese director Hirokazu Kore-eda is superbly unforced and unassuming, finding delicate notes of affirmation and optimism and discreetly celebrating the beauty of nature and family love. It is watercolour cinema with nothing watery about it, in the classic “family drama” vein that you might associate with Yasujirô Ozu, though in conversation at Cannes last year – where I first saw this – the director told me his inspiration was more Mikio Naruse. Our Little Sister is not as challenging and overtly painful as his previous films I Wish or Like Father, Like Son, and there might be some who find it a bit tame or even sentimental; I can only say there is something subtly subversive in the emotional dynamic Kore-eda creates with having three or four women on screen. It is adapted by Kore-eda from the manga Umimachi Diary by Akimi Yoshida, and tells the story of three twentysomething sisters, who live together in a handsome house originally belonging to their grandmother. Yoshi (Masam Nagasawa) works in a bank and is reasonably happy with her job and her single status but drinks too much. Chika (Kaho) works in a sports shop and is the baby of the group. Sachi (Haruka Ayase) is a nurse at the local hospital: beautiful, poised but emotionally frozen, unhappily involved in an affair with a married doctor. She has recently been offered promotion, which would mean working in the terminal ward – perfectly sensible of how honourable and worthwhile the job is, but unhappily aware of it being somehow ominous for her personally. All three have long since been estranged from both parents. Their father left them to live with another woman, with whom he had a child before moving on to wife number three. Their mother walked out, too, leaving them in young adulthood in the family home. But, when they receive news of their father’s death and go to the funeral, they meet their sweetly charming teenage half-sister Suzu (Suzu Hirose) and decide on the spot that she must come back and live with them. Their new little sister is a complicated miracle in their lives: she diverts them, pleases them, almost like a grownup doll. She is remarkably well adjusted, happy in her new home and happy at school. They adore Suzu and love looking after her; she gives them a new purpose in life and a new kind of personal direction, and yet her existence reminds them of their own orphaned situation and weirdly infantilised existence, babes in a gradually shrinking wood of their own making. Suzu might actually be making this worse. Even before she showed up, they were emotionally stagnant and becalmed. They are hardly more grown up than Suzu. Are their lives going backwards? It is a richly pleasing film, bringing in the classic imagery from the Japanese provincial family drama: rural train journeys, group meals, and discussions linking family and food, thoughtful bucolic walks uphill – denoting humility and patience – melancholy funerals and some wonderful seasonal compositions. Self-effacingly and unobtrusively, the director gives an easy swing to this quartet’s life, moving calmly from the home to the school, from the private sphere to the fraught public world of the workplace. Nothing is emphasised too much, voices are not raised very greatly, even in moments of great stress; nothing in the drama or the direction is very strenuous, and yet it accumulates in power. Just as when I saw this the first time, I loved Suzu’s innocently ecstatic ride on the back of a bicycle, turning her face to the sunlight. Watching this film is a vitamin boost for the soul.

Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian, 14 April 2016.

What you thought about Our Little Sister

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49 (64%) | 23 (30%) | 5 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 77 Film Score (0-5): 4.57 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

125 attended our last screening and the response rate was 62%. Many thanks to you all for taking the time to tell us your views. Comparing this result with others during the season it generally seems easier for you to provide positive comments when a film has engaged and moved you emotionally. The following note reflects many of your opinions: “A beautiful, graceful film. Tackling some meaty themes of life and relationships like abandonment, betrayal, illness and death; as well as hope, trust, respect and happiness...but delivered with restraint and subtlety. No violence, no sex, no swearing (well hardly), no shouting or screaming histrionics...yet the performances were powerful, natural and convincing. Visually gorgeous too, great cinematography. Up there with La Famille Belier and Tangerines in my top three films of the season (that I haven't seen before)”. And this also; “In a society where the norm is for great deference to older people, especially within the family, this exquisitely paced film goes right to the heart of the conflict between the generations when the older ones do not behave appropriately. Assisted by beautiful photography and excellent acting by the sisters, the great skill of Director Koreeda is well demonstrated when the deep anguish felt by the young ones is expressed so clearly with just a few words, an enigmatic smile or a sideways glance from a young face under a Mary Quant hairstyle”. Other members told us that this film was “a very gentle portrait of modern family life. Wonderful interaction between the four sisters – accepting their step sister rather than rejecting her and all the richer for it”. “Perfect in every way. Wonderful photography, sensational music – a film that will live on in the memory when all others fade away. More (if there are any this good) like this please”. “Very charming and well-acted”. “Food, funerals, families!! I really enjoyed it”. “Simply stunning – another wonderful contemplative Japanese film. Keep them coming! The colours at times were just wondrous. The only negative: Sachi’s last line – it was unnecessary – could have been done with a camera shot alone if at all”. “Loved seeing life in provincial Japan”. “Beautifully shot. Wonderful score. A film to wallow in”. “A delightful film”. “A lovely gentle film – of love and loss and the Japanese way of life. Beautifully portrayed”. “As someone with four sisters, I loved the quips, the gripes, the banter, the tiffs and the love the film portrayed between them all. I loved it”. “A lovely film of a loving family. Brilliant camera work and direction”. “A film to make you smile”. “What a beautiful “feel good” film”. “A delightful and moving film. Beautifully acted and such glorious scenery too. More please! Subtitles were perfect also”. “So beautifully drawn and nicely understated. The insights of life; complications, obligations and morals. A wonderful insight to Japanese culture and life at a seaside town”. “Film making at its best. A human story filmed respectfully. Thank you GFS”. There are more observations on the website. “I very much enjoyed this film yesterday evening and would rate it as Excellent. When I submitted my comments on a recent film I stated that the kind of film I liked to see at the film society was the world cinema film giving me an insight into the everyday life of people in countries I am unlikely to visit. Our Little Sister did exactly that. It was one of those films where you become so involved in what is happening that you completely forget your surroundings. There was an atmosphere of calm about this film even when it was dealing with everyday events such a train trips and shopping in the market. Nothing jarred although the film was about subjects which could have resulted in fierce arguments and shouting amongst the various relatives and probably would have done so in a film made in America. Even the open and friendly faces of the sisters contributed a strange peacefulness to the film. I loved the Japanese formality and respect both at the funeral of the father and the subsequent memorial service for the mother. But even the everyday relationship between the older sisters and their recently introduced younger sister was conducted with a respectful distance and formality. The introduction of the younger sister to her new school friends was also an interesting moment. Food played a prominent part in the film and reflected how love can be shown by the provision of simple meals that give pleasure without any words being spoken. This was true both of the family and the restaurant owner. It also showed the treasured memories we have of shared family meals and our introduction to family customs by our parents, as demonstrated by the whitebait toast and the plum wine”. “I feel like I have taken a long comforting bath!” “Beautifully filmed – loved the way all the sisters interacted and all the attention to daily life – cooking- making plum wine and such kindness and harmony. Good to have a vivacious Japanese film for a change”. “A really lovely film. The four actresses playing the sisters were so natural and the scenery beautiful. I was amazed at the politeness of the Japanese – I hope they are all like that”. “The film provided an insight into a Japan that I was totally unaware of. Although it was quite slow, I enjoyed seeing the cultural differences”. “Some lovely scenery but the film was too long and disjointed”. “Visually very beautiful – lovely blues. Loved the music but I thought the storyline rather bland and long drawn out”. “Beautiful rhythms, astonishing young performance by the little sister. Cloying music!” “The cumulative effect of tiny details made a great whole”. “A kind and gentle film about loss and reconciliation…well shot in pastel colours. Very good acting …slightly shaky stereotyped characters but well-drawn”. “A slow development of beautiful personal relationships”. “Not as good as his previous films but enjoyable none the less. Beautifully filmed. Music reminded me of the Mahler in “Death in Venice”.” “A really good “bonding” and coming of age movie. Great understated actions – beautifully shot and atmospheric – all delivered without a plot just scenes running into one another”. “Very long, no car chase. I’m glad nothing went wrong”. “Too long and unlikely”. “Not as immersive as I expected”. “Like several before, this understated family-centred film provided a really engaging, authentic window into another culture. One felt the appeal of this more ordered society but was left wondering to what extent this formality constrained honest, open emotional dialog. A very enjoyable film!” “I would rate this as excellent. I felt totally relaxed after watching those beautiful young women in a backdrop of washed out cinematography which highlighted the detail of the figures within. The scene of the girls on the beach at the end was simply lovely”.