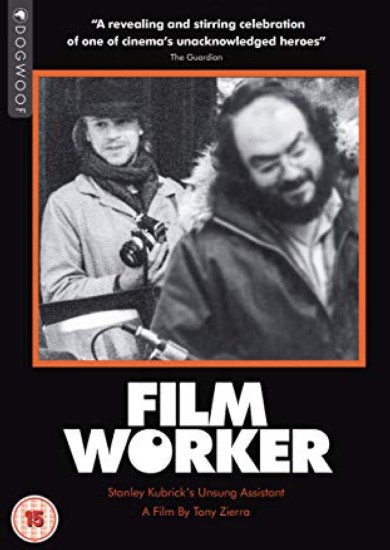

Filmworker

Documentary about Leon Vitali, who gave up his acting career to become Stanley Kubrick’s right-hand man for 30 years. Previously unseen photos, videos and anecdotes from actors, family and crew members add insight into Kubrick and his methods.

Film Notes

‘Filmworker’ Review: Doc on Kubrick Collaborator Is Case Study of Obsession

Portrait of Leon Vitali charts a 30-year working relationship between perfectionist director and his most devoted disciple.

There’s being someone’s right-hand man, and then there is Leon Vitali. A strapping young lad who had begun making a name for himself in the early Seventies, this British actor had built up an impressive resumé of theater gigs, supporting parts, cop-show cameos and sitcom ensemble roles – he was being groomed as the hot new thing, a gentler, ginger next-gen Angry Young Man. One day, he walked in to a theater and watched a bunch of white-jumpsuited thugs pillage their way through a teenage-wasteland London. The movie was A Clockwork Orange. The director was Stanley Kubrick. I want to work for him, he told a friend as they left the screening. You should always be careful what you wish for.

Filmworker, Tony Zierra’s extraordinary documentary, dives in to what happened next: Vitali’s agent calls him, saying that the American ex-pat was adapting William Thackeray’s 1844 novel Barry Lyndon and was interested in the actor for the role of the dastardly Lord Bullingdon. After wrapping in July of 1974, Vitali moved on to other gigs, but they paled in comparison to being in the presence of a cinematic genius. Then Kubrick sent him Stephen King’s The Shining, with a note that simply said: “Read it.” He asked the performer if he could help find a child to play the movie version’s psychic youngster. Vitali said yes – and ended up employed by the filmmaker as an all-purpose guy Friday, acting coach, archivist, casting director, Foley Artist, designer of feline surveillance systems, personal assistant, sounding board, punching bag and much more for the next 30 years of his life. Not even Kubrick’s death in 1999 could keep the acolyte from serving his perfectionist deity in perpetuity.

Taking its name from the designation that Vitali gave himself when asked his occupation on travel forms, Filmworker charts the duo’s master-and-servant relationship from project to project, and to say this is manna for Kubrick fans would be an understatement. You want first-hand testimonies on the cinematic godhead’s directorial process? (Vitali recounts reading Lyndon lines while the auteur prowled around, checking every angle and peering through every lens, then rinse, repeat.) Do you crave behind-the-scenes anecdotes on making Full Metal Jacket and Eyes Wide Shut? (Check, and check.) Ever wonder what happened to The Shining‘s now-grown child actor, Danny Lloyd? (He’s interviewed here, testifying to how Vitali was his best friend and spirit animal on set.) There are stories galore here, tales of 30-take scenes and impromptu casting changes and artistic eccentricities that will have film geeks howling with joy.

David Fear, Rolling Stone magazine, May 9th 2018.

Warm, Witty, Wise ‘Filmworker’ Honors Stanley Kubrick’s Extraordinary Right-Hand Man [IDFA Review.

Many words have been written, and doubtless many more will be, about the filmmaking genius of Stanley Kubrick. But if, as Thomas Edison said, genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration, Tony Zierra’s “Filmworker,” which showed in nearly completed form at the International Documentary Festival of Amsterdam (IDFA) after bowing in Cannes Classics in May, is dedicated to the far less familiar name who contributed a great deal of that sweat.

Leon Vitali is known to Kubrick fans as Lord Bullingdon, the petulant stepson of Ryan O’Neal‘s eponymous rogue in “Barry Lyndon” (and to real aficionados also as the masked and robed Red Cloak in “Eyes Wide Shut“). But less common knowledge is what become of the pretty, soft-faced young man playing Bullingdon after the curtain fell on that final scene in which he watches inscrutably as his mother signs Barry’s buy-off check. That’s the story that “Filmworker” tells, somewhat shaggily but with a great deal of infectious affection, and it builds to a deeply moving portrait of Vitali’s own gift: his genius for the kind of unquestioning dedication and steadfast graft that is seldom recognized in the annals of cinema’s Great Men.

“I want to work for that man,” Vitali says he told his companion, awestruck, as Kubrick’s credit rolled up at the end of “2001: A Space Odyssey.” And where that assertion might, in any other memoir, be a finessing of the truth, we quickly learn to believe everything Vitali tells us: he hasn’t got a self-mythologizing bone in his body. This is all the more extraordinary for an actor — often ranked among the most ego-driven of professions — and it certainly wasn’t that Vitali was struggling in his job. Through a rapid montage of his pre-‘Lyndon’ early roles in British movies and TV shows (the archive footage selection is a continual delight across the whole film, often very wittily edited to illuminate or comment on a particular chapter in Vitali’s life), it’s clear that the mop-headed young Vitali was doing okay for himself. And of course, he had promise enough to catch Kubrick’s eye when he went in to read for ‘Lyndon’ and talent enough that the writer/director significantly increased his role.

But this is the point at which Vitali’s story diverges from that of many of his peers, such as Ryan O’Neal and Matthew Modine (both frank, funny interviewees here). Vitali took just one more major role (as Victor Frankenstein in a Swedish-Irish “Frankenstein” adaptation), and only did that because the director promised to allow him to sit in on the editing process and learn that craft. Now “upskilled,” he contacted Kubrick again, who gave him a Stephen King book to read and promptly sent him to the U.S. to cast a kid in the role of Danny Torrance.

He found Danny Lloyd (also interviewed) who so imprinted on Vitali as his friend on set that some fascinating behind-the-scenes footage shows that it’s Vitali’s voice shouting Kubrick’s direction to the little boy (“Give me the scared look, Danny!”), and jogging alongside the camera rig as Danny barrels along on his trike. But Vitali wasn’t just wrangling actors, running Jack Nicholson‘s lines with Lloyd and Shelley Duvall and Scatman Crothers, he was also acting as general factotum to Kubrick’s quicksilver demands — a role the word “assistant” barely begins to cover.

From that moment on, it seems, Vitali was hardly ever away from Kubrick’s side, and there was not a single aspect of the filmmaking process with which he did not have to make himself acquainted, from foley work to child labor regulations to color grading to the obsessive cataloguing and examination of more or less every extant print in Kubrick’s back catalogue. “Filmworker” shows him tutting over VHS artwork not done to his exact specifications; laying to rest some pretty arcane aspect ratio geekery; rummaging through boxes and boxes of fanatically detailed notes and reminiscing about installing monitors all over Kubrick’s house so the director could keep an eye on his beloved but ailing cat, Jessica.

He is a trove of anecdotes about life on set and off with Kubrick (did you know it was Vitali who suggested that the little girl ghosts in “The Shining” be twins? Or that he and R. Lee Ermey basically conspired to get Ermey his “Full Metal Jacket” role despite Kubrick having cast someone else?). And he’s often very self-deprecatingly funny, recalling how people would come up to Kubrick in later years and say “I’d give my right arm to work with you,” and he could practically feel Kubrick thinking “Just your right arm? Why are you lowballing me?”

Vitali himself gave Kubrick everything, and it took a toll. Our first look at the haggard, bandanna-ed man of today is a shock after the image of bouncy youth in those early roles. Almost every interviewee marvels at how he never slept; his children recall him being there but not really there, constantly on the phone or working amid jumbled stacks of correspondence. Indeed it comes as a bit of a surprise when his kids are introduced — one wonders when Vitali put aside the time to conceive them.

But despite all the commentators who seem determined to frame Vitali’s story as a kind of tragedy (perhaps because many of them are actors themselves who cannot imagine a career spent in someone’s shadow could be a triumph), Vitali is magnificently without rancor toward Kubrick himself. “Filmworker” (which is what Vitali wrote with typical humility back when passports had a “profession” section) does tease an exposé of Kubrick’s well-documented “difficult”-ness, but while Vitali is frank about the nature of his demanding and subservient relationship to the man, his warmhearted, dazzled, Everest-high respect for Kubrick’s talent remains undimmed even now.

It is truly inspiring and touching just how little bitterness Vitali has in him, and it stems from his having no regrets over a life dedicated to something he believes in with utterly selfless purity. “How honored was I to be able to work with him?” he says at one point. The honor might be his, but the gratitude should be not only Kubrick’s, but all of ours. Cinema would be much the poorer without Stanley Kubrick’s legacy, but “Filmworker” emphatically proves that Stanley Kubrick’s legacy would be much the poorer without Leon Vitali. [B/B+]

Jessica Kiang, The Playlist, November 26th 2017.

What you thought about Filmworker

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 (28%) | 16 (50%) | 7 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 32 Film Score (0-5): 4.06 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

54 members and guests attended which with 32 responses gives a hit rate of 59%. Many of you echoed this comment. “Fantastic insight into the life and work of someone who I was completely unaware of being such an influence on so much work I have enjoyed”. “A fascinating documentary! I had not registered the name Leon Vitali, though I totally enjoyed Barry Lyndon and the Lord Bullingdon character. Vitali came across as a very self-effacing, but not an unhappy, person. Good to know more about the person that supported the creative genius Kubrick & helped to bring the ideas to fruition on the screen”.

“A fascinating film about the dubious merits of subsuming one's own artistic career in service of a greater talent. What is inspirational is the absence of ego in Vitali and the evident peace, pleasure and satisfaction he gains from his devotion despite the horrendous workload. What is curious is that he somehow managed to have three children. The cornucopia of film set footage and intriguing insights into Kubrick's work methods are riveting for any fan of his films or indeed seventies TV - was that 'The Fenn Street Gang'? Vitali himself seems the most gentle and patient of guides and retains a Zen like calm despite having worked for so long in what must have been the most trying of circumstances. A slight shame there is no comment from many of the other actors involved but a marvellous film nonetheless”.

“I am not a "Kubrick-phile", of the films I have seen I think some are excellent and some so-so. But regardless of the director this was a fascinating story of one man's total dedication of his life in servitude to another. I actually found the story quite tragic, and it reflected very poorly on Kubrick as a person to see not just what was demanded of Vitali but also to learn he ended up in financial difficulty while Kubrick was clearly wealthy. And you can't help wondering just how successful Kubrick's films would have been without Vitali's support. And yet Vitali would probably be aghast by my views, because he seemed totally genuine in continuing to feel blessed that he had been able to work so closely with Kubrick for all those years”. “I found it totally gripping, something I wasn’t expecting from a documentary. An ode to the unsung heroes in our lives. It was a candid yet tender portrait of a man who had devoted his life to his hero and who had subjugated his own ego and needs in order to enable Kubrick. Vitali really did suffer for the art form that he loved through the relentless hours and range of roles he played in the film-making process. That was something that came across - the sheer number of unsung talented people involved in bringing this art form to an audience. It was obvious to those around them that Vitali was key to Kubrick’s success but the fact that he was left penniless after Kubrick’s death points to the fact that he wasn’t financially rewarded for his endeavours or properly cared for. Or maybe he blew it all - Vitali’s son didn’t elaborate. We didn’t learn very much about his family, which was a pity. How did he even have time to start one? “

“Mildly interesting, but felt not especially insightful. I expected more about either how Kubrick worked or what Vitali learned about how Kubrick worked. There seemed to be a lot of ‘wow didn’t he work hard’ without a lot of illumination”.

‘An unusual film about Leon Vitali transforming his career as an Actor to a Filmworker for the acclaimed Film Director Stanley Kubrick. Unusual in that a Personal Assistant to a Director is not normally acknowledged within the film industry. A professional ‘marriage’ from when they met in 1974 until Kubrick’s death in March 1999. Vitali was credited in the Shining as Personal Assistant to the Director for the film The Shining as well as Eyes Wide Shut. What influence did they have on each other for Kubrick to produce such a critically acclaimed film The Shining with his controversial dark humour and realism and other films of the same ilk after this film. Vitali appeared heartbroken as he spoke of Kubrick’s death. The 2 ½ hour telephone conversation between Vitali and Kubrick the night before Stanley Kubrick died; it would have been interesting to gleam some of the content of the conversation to understand their relationship more clearly. Leon Vitali to restore the film and sound material of Kubrick’s work is an honour to him for it appears no one understood Stanley Kubrick film techniques more than Leon Vitali’.

“What dedication and sacrifice. How sad and very moving”. “Fascinating insight into the filmmaking art and one man’s dedication (selfless) to it”. “Very interesting documentary. Probably one of the best I’ve seen”. “A very watchable documentary. Remarkable stories of a selfless Filmworker devoting his life to a visionary director”.

“Such an insight into a famous director. How unpleasant Kubrick sounded and what a martyr Leon was and very sad at the end”. “Fascinating glimpse behind the lens. Extraordinary man”. “Interesting. A shame that Leon Vitali never got the recognition that he clearly deserved”. “Interesting insights into Kubrick’s film making. But sound poor”. “Very interesting”.

“Interesting, rather laboured and definitely too long”. “Leon certainly deserved a documentary. His obsessive, tireless work on behalf of “the Master” was astonishing and one is surprised that he survived physically, but it was clearly an intense, two way relationship that worked”. “A bit too long – needs an editor”.

“Fascinating insight – film did seem too long”. “Interesting but about an hour too long”. “Interesting insight into what sacrifice has to be made to work for a perfectionist”. “Interesting – but almost as much about Kubrick as Vitali and left a lot unexplained”. “Long winded but glad I saw it – interesting”. “Interesting insight into the all-encompassing life of a film worker”.