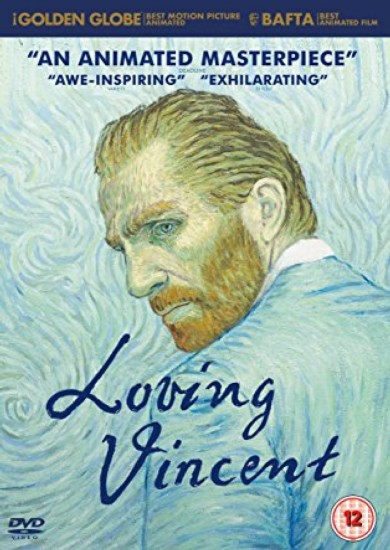

Loving Vincent

Entirely brought to life by over 65,000 individual oil paintings, this animated film delves into the final days of Vincent Van Gogh’s life.

What's this?

Film Notes

Loving Vincent review: a beautifully textured tribute to Van Gogh.

The fact that the process that took six years, would be remarkable enough in itself. But painted to look exactly like the work of Vincent van Gogh? That’s something else. Corn fields shimmer and rustle with slight flickers of the impasto. The night sky sparkles and swirls. And faces – even the recognisable ones of a noted British cast – pose for a set of portraits that are rarely short of captivating.

The directors are British animator Hugh Welchman and his wife Dorota Kobiela, a Polish-born artist. They worked with 125 artists to paint the film’s 65,000 individual frames, inspired in each sequence by specific van Gogh paintings. Footage was shot of the cast playing out scenes on rudimentary sets, then this was projected on to canvases, frame by frame, and painted over. The visual effect is overwhelming, a luxurious immersion in the palette and environment of a celebrated artist.

The script is somewhat more down-to-earth, with the occasional feel of a biographical walk-through that you might hear acted out on a museum tour. Van Gogh himself is the mystery at the bottom of it, rather than the central figure. It’s set a year after his death, with family friend Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth), who has been sent by his father (Chris O’Dowd) to deliver a letter to Vincent’s brother Theo, trying to puzzle out the artist’s state of mind when he died. Addressed is the theory that van Gogh may not have taken his own life, but been shot by a disturbed teenage boy.

As biopics go, it’s psychologically rudimentary: the flashbacks to friendships Vincent experienced, which switch to sharper, more contrasty black and white, are academically parcelled out and don’t hold many surprises. Instead, it’s all about surrendering yourself to the textures of scenes – the tinkling of cups in a tea-room, the sounds of bickering in a bar. Clint Mansell’s elegantly mournful score does an important job in knitting it all together into a flowing piece of embroidery you want to stay with. And the novelty of seeing Saoirse Ronan’s face, and Helen McCrory’s, and Aidan Turner’s, converted into moving-image portraits by these disciples of van Gogh’s style, remains considerable to the end.

To be fair, the film perhaps runs into the mere bad luck that cinema has done pretty well by van Gogh in the past: especially the two wonderful creations by Vincente Minnelli (1956’s Lust for Life) and Maurice Pialat (1991’s Van Gogh), not to mention an Altman one, and so on. A further forthcoming biopic, starring Willem Dafoe and directed by Julian Schnabel, will adopt a first-person point of view. One thing’s for sure: a curio it may be, and skimpy on the human element, but Loving Vincent certainly doesn’t skimp on the beauty or the brushstrokes.

Tim Robey, The Telegraph, 12th October 2017.

‘Loving Vincent’ review: Hand-painted movie about Van Gogh is exquisite.

You have, I am certain, never seen anything quite like “Loving Vincent,” which is being promoted as the world’s first entirely hand-painted movie. It’s an animated film, but that descriptor isn’t quite accurate: To tell this story about a mystery surrounding the 1890 death of artist Vincent Van Gogh, filmmakers Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman assembled a cast, found period-appropriate costumes and sets, and shot the film. Then the real work began: Every frame — more than 65,000 of them — was hand-painted over in oil paint in the style of Van Gogh, by a team of more than 100 artists.

The result is a curious and often exquisite blend of two art forms. With settings and characters inspired by a number of Van Gogh’s paintings, the film unfolds as if the viewer fell asleep in a museum and dreamt of art that came alive. Blue clouds swirl over a village; a night sky blinks with lacy stars; a butter-yellow sun sinks over a tangerine-colored field; a dim tavern is lit by gold and green rings of light — all rendered in visibly textured brushstrokes. Rain falls in dashes of straight gray lines; a head of blond hair catches a bit of blue from the sky.

“Loving Vincent” is almost too beautiful for its own good; I found myself, too often, so dazzled by the form that I quite forgot about the content. If this script had been conventionally filmed and released, I suspect the movie might be quickly forgotten; the story, which moves backward and forward from Van Gogh’s life into events after his death, doesn’t feel fully developed. But that doesn’t really matter; it was a pleasure to become happily lost in this unique film’s world of color and line, and to see two filmmakers’ mad dream come true.

Moira Macdonald, The Seattle Times, 17th October 2017.

What you thought about Loving Vincent

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 39 (60%) | 19 (29%) | 6 (9%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 65 Film Score (0-5): 4.48 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

136 members and guests attended this screening and 65 responses delivered a hit rate of 48%. The score of 4.48 ties Loving Vincent with In Between for most popular film of the season so far. Although 89% of the comments rated the film as Excellent or Good, there were some reservations about the overall viewing experience and satisfaction level. However, I have focused on the most positive for this selection. All comments may be found on the website...all 3 A4 pages of them!

“What an extraordinary project. Briefly reading about it in advance, I expected something rather unconvincing, yet every aspect gets 5 stars. The whole concept, and the faith that it would all work in the end, is breath-taking. As an admirer of Van Gogh’s work, I loved the whole concept of bringing the pictures to life, and I think this works – better in the ‘live’ colour sections than the flashbacks, which at times were a bit ‘smooth textured’. And then building scenes around the pictures, which follows logically from the core idea but is implemented almost seamlessly. A very minor criticism that some of Van Gogh’s popular ‘tricks’ (like the star haloes) were a bit over-played, but generally the use of light and in particularly the way the light moved was masterful. Likewise the sound, down to accurate bird calls. How they could have been able to visualise how it could turn out beats me. In a sense, the story is secondary, and yet the story (however much or however little is factual) is also well-told and worth watching, especially since it had to be constrained by the use of one picture after another. But what on earth do they do next?”

“A “tour de force”. Amazing. Want to sit through it again now! The concept and outcome really different. Loved it”. “A brilliant production”. “Very well done”. “Brilliant illustrative and unique film of the life of a genius”. “One of the most beautiful amazing films that GFS have screened. Wonderful from start to finish and so clever. No wonder the film took so long to make. Perfect cast too”.

“I had heard wonderful reviews of this film and it lived up to my expectations”. “An amazing undertaking! Extraordinarily convincing once one’s eyes had got used to the jumping motion of the brush strokes. Loved the faithfulness of Van Gogh’s palette. Fascinating”. “Brilliant. Could watch it all over again!” “Absolutely superb. An excellent idea, wonderful artistry and beautifully executed. Thank you for selecting it”. “Brilliant”. “Wonderful idea, brilliantly executed. A great tribute to a great painter”. “Brilliant animation. Quite amazing”. “Beautifully filmed and such a fascinating idea. I loved this film with its gentle views and guarded characters slowly revealing themselves. Starry night – great ending”. “Beautiful. The paintings came to life”. “A superb film – tragic, poignant and awe inspiring visual effects”.

“What a fascinating film. The technical achievement itself was amazing! The combination of real actors & animation was clever too. I knew little detail about Van Gogh’s life so the story held me though it was slow in parts. 7 out of ten from me!”

“After the short introduction into the making of this film, I very much wanted to like 'Loving Vincent'. So much research and dedicated work by so many people had gone into its production. And yet, I was disappointed. The novelty of the idea of reproducing the film as a moving painting by van Gogh quickly wore off for me. Van Gogh's brushstrokes, so exciting when looking at his actual paintings, soon became irritating by their constant flickering. To make the young man in the yellow jacket the central character was a brilliant idea. The acting was great, the actors well-chosen and the musical score helped blend it all together. Yet, the script was thin. The theory that van Gogh might not have killed himself but had been shot is not new and his closeness to his brother Theo well known. This viewer, while appreciating the considerable visual achievement, still did not like the film. I prefer the real van Gogh”.

“Although I much admired the skills of the painters and animators who made the film, I didn't actually enjoy the film very much. I felt it was a bit like a "who done it" film, without much substance, and didn't tell me much about Van Gough at all. The constant flickering of the animation I thought was a little distracting.”

“An extraordinary concept and very good idea to show the "how it was made" short first. However, I was not sure how well Vincent's style of painting translated into animation. It didn't always make for easy watching and I'm not sure did justice to the beauty of some of his better known paintings. The variety of accents was also a bit confusing and I thought Armand sounded like he was trying to do a Michael Caine. Having said all that I did enjoy it and thought it was an amazing achievement to have put it all together. Thanks.

“Visually, a striking piece of filmmaking, maybe a moving work of art. The oil paints seem to glide effortlessly over the subject matter creating scene after scene. The fantasy of making paintings come alive is very old, and it was often hypnotic and beguiling. The images recall a passionate, hard-working artist, but not always the tormented, suicidal genius of legend. Enjoyed the black and white flashbacks as they seemed to jolt us back to more mundane events. It truly is a feast for the eyes. The story elaborates on the events leading up to and after Van Gogh's untimely death. His demise is still shrouded in a great deal of mystery. Did he kill himself or was he murdered? It's surprisingly engaging as a detective story for a time but then it meandered too much, even and principal mystery is the stuff of police procedural, as Armand doggedly tries to reconstruct van Gogh's final weeks and shed light on the circumstances of his death. We still don't find out why he was miserable towards his death. What secrets did he have? What enemies had he made? The questions are interesting, but not quite sufficiently dramatized to sustain "Loving Vincent" for its full length. As the story limps and drags, the viewer also becomes accustomed to the images, and astonishment at the film's innovative, painstaking technique begins to fade. But it's still charming and that never quite wears off, for reasons summed up in the title”.

“This film is astonishingly ambitious and a remarkable achievement visually, bringing Vincent's most famous canvasses to life, though I did feel this worked most convincingly with the landscapes. When the animated actors intrude is when the problems begin. On the visual side the animated portraits are harder to watch, the painterly brush strokes somewhat distracting, the black and white sequences work rather better in this respect. Curiously, given the strong cast, the acting is rather wooden, labouring with a sluggish, procedural and overly explanatory script and the visual excitement breaks down when there are animated heads against a still background of huge brush strokes. A fascinating visual masterpiece but a flawed film”.

“Amazing accomplishment. Not sure about the English regional accents”. “Very enjoyable. Unusual. Visually stunning”. “Clever idea, beautifully executed. Excellent soundtrack. Best film to date!” “A fascinating film – a real work of art. Interesting – it was good to see the short beforehand – explaining how the film was made”. “Completely original – a first for me – a detective story - still unsure of the death. A future classic!” “One of the most original and moving films I have seen”.

“Brilliant how the painting and story behind them were brought to life. What a tragic end to such a talent”. “Visual tour de force; the storyline was more pedestrian but some real human interest in it. Ravishing paintings”. “Truly enchanting. Fabulously told story – a true masterpiece. The fascination of his life and death continues”. “BRILL”. “What an amazing film. Astonishing to see the paintings seemingly come to life”. “Incredible”. “Amazing work by artists. Interesting background to the Van Gogh story”. “Innovative; a visual masterpiece”. “A delight to watch”. “Excellent animation and very clever, let down by odd accents”. “Quite remarkable in every way – particularly liked the black and white actually”. “Great production”. “Fascinating. Very clever form of animation”.

“An interesting film if a little long. A pity that the “worded scenes” ended before one had time to finish reading them”. “An amazing project on which to embark and to fulfil”. “Visually stunning. Slow to start but eventually compelling – but I am a Van Gogh …” “production was certainly a “labour of love”. Technically brilliant. Very good to see the short detain the process”. “Visually magnificent. An artistic treat but the script did not quite match the visuals”. “Clever but odd”. “Did not like the constant shimmering effect”. “Technically very impressive but I didn’t find the characterisation particularly convincing especially Armand. The constant flickering was distracting and the very modern colloquialisms jarred. Sad ending though, which brought home the tragedy of Vincent’s life and death”. “Undermined by the central character – unreal”. “Visually impressive, but that was all. The creators of the film seem to have fallen in love with their technique and produced a film that was disconnected and inconsequential. The…imagined scenes and flickering canvases eliminated any sense of reality. I was not surprised that the person sitting next to me spent most of the time asleep”.