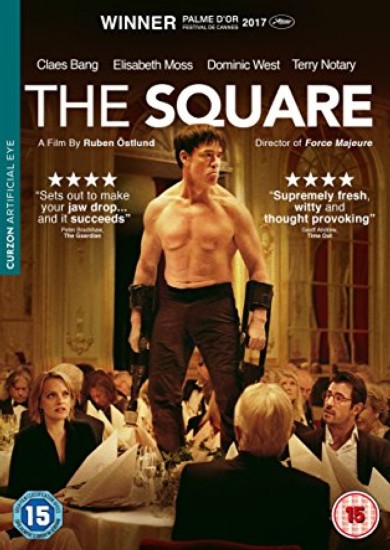

The Square

Challenging and controversial social satire about a curator at a prestigious Stockholm museum who finds himself in crisis as he sets up an exhibit. Winner Palme d'Or 2017.

Film Notes

Film of the week: The Square artfully exposes hidden injustice

Ruben Östlund’s museum-set satire contrasts the prestige of high culture with the thankless work of helping people, with unpredictably uncomfortable results.

As the world becomes increasingly saturated with visual media – with screens in our pockets, in restaurants, in elevators, taxicabs, vending machines and all sorts of places where they didn’t used to be – our collective visual literacy doesn’t seem to be keeping up. This is probably because arts programmes are the first to be cut in publicly funded schools, and when they do exist, it’s on a specialised track. It’s also undeniable that international art-speak (the semi-academic, self-important, totally incoherent language of gallery press releases and artists’ statements) and the perceived frivolity of mid-century conceptual art (ie the ‘my kid could do that’ refrain) have undermined art’s place in the public’s interest.

Yet the cloistered, fundamental silliness of the contemporary art world is not Ruben Östlund’s target in The Square – that would be too easy. As with his previous films Play(2011) and Force Majeure (2014), Ostlund uses his setting to explore hidden inequalities in supposedly liberal societies, particularly those concerning masculinity, race and class, playing with our expectations about what is supposed to happen versus the results, which are always uncomfortable.

The Square is set in a Sweden where the monarchy has been abolished; the royal palace in Stockholm is now a non-profit gallery of contemporary art, aptly titled the X-Royal Museum. Christian Nielsen (played by the unequivocally handsome Dane Claes Bang) is head curator, competing with art collectors to get the latest and greatest works that question our relationship to space and the notion of being a good person. (Arrows pointing to and from the eponymous installation are labelled “I trust people” and “I don’t trust people.”)

However, Christian’s life is, like our own, grey to black: after having his mobile and wallet stolen (in a choreographed grift that could itself be performance art), he tracks the thief to a rundown apartment block and attempts to retrieve his property by distributing threatening letters to every flat. He quickly gets back the stolen items, but also begins to receive more things (cufflinks, other mobiles) and even an enemy: a small Arab boy whose parents have punished him severely because, thanks to Christian’s actions, they believe he’s a thief.

The fallout from this retrieval operation causes Christian to neglect his duties at work, which is why a wildly offensive YouTube video to promote The Square gets his approval. (In it, a blonde homeless girl holding a pitiful-looking kitten is blown up inside The Square). During the pitch meeting, the hip marketing guys start by stating, “Your competition isn’t other museums but natural disasters, terrorism and controversial moves by far-right politicians.” While this is undoubtedly true – the internet flattens outrage into a single continuum without any sense of the scale of importance of these very different events – Östlund doesn’t dwell on the point. Instead, like the internet itself, he simply moves along.

Throughout the film there are many small gags and standalone vignettes – half-Tati, half-Vine – that take a stab at the contradictory, unequal nature of western liberalism. Östlund never explicitly says that the museum’s staff is diverse in name only, but rather shows how the one female assistant and one black assistant are stuck doing low-grade tasks (directing guests to exhibits, sorting out Christian’s mobile) and are ignored during the YouTube presentation. Likewise, The Square never spells out the facile nature of the X-Royal’s mission, but makes it perfectly clear through silent shots of the art (a giant pile of schoolroom chairs, for example), the disinterested visitors and Christian briefly admiring the work of a pet chimp.

Glimpses of life outside the museum frequently show people begging for change, nudging at the question of the prestige of helping art versus the often thankless task of helping the poor. The only beggar Christian decides to help insists he buy her a sandwich without onions, but he finds this request rude and so fails to comply. The mechanics of Christian’s personal and professional downfall are completely tied up in this inability to interact with the world in a way he doesn’t perceive as polite or self-protecting – he only bothers to do what he thinks is right for him, not what might be right for the other person. This plays out in his casual relationship with Anne, an American journalist (Elisabeth Moss). He is a man continually undone by the awareness of his privilege, and while the ending provides some sense of hope, it’s tenuous.

Violet Lucca, Sight and Sound, 9th April 2018.

You’ll Probably Argue More About “The Square” Than Any Other 2017 Movie

Ruben Östlund’s Palme d’Or winner forces us to confront our own values, and how we see ourselves.

Ruben Östlund’s The Square, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this past May, probably says more about the times we’re living in than any other film you’re likely to see this year. And yet the beauty of the movie is that everybody will have their own ideas about what, exactly, it is saying. It’s not a vague film, however. Östlund is specific and exacting as a writer and director, and within The Square’s empty spaces, we’re forced to confront our own values, and our own visions of ourselves.

That idea is, in fact, what The Square is literally about. In a contemporary art museum in Sweden, chief curator Christian (Claes Bang) prepares to host a conceptual art project called “The Square,” which is described as “a sanctuary of trust and caring. Within it we all share equal rights and obligations.” One could look at this square — it’s an actual square, by the way, carved into the middle of the courtyard of a royal palace — and lament the fact that the world has gotten to a point where such values can only be practiced in a small, four-by-four meter space, and only as part of an art project. Or one can see in it an example of the kind of idealistic and utopian thinking that could potentially sink a society. (What the hell does “a sanctuary of trust and caring” even mean, exactly?)

The language describing the installation suggests that humanity’s natural state tends toward equilibrium and fairness — or that these can at least be achieved by a kind of quiet, willing consensus. When such thinking meets the real world, of course, chaos ensues, and through its somewhat loosely connected, often hilarious vignettes, Östlund’s film questions our understanding of honesty, trust, and fellowship. Be it through a bizarre argument in the wake of a sexual encounter about what to do with a used condom, a creatively calamitous plan to retrieve a stolen phone, or a craven approach to marketing “The Square” itself, the film’s scenes suggest that our notions of integrity and community might be a lot more fragile than we think.

To add an extra layer of symbolism, “The Square” has been placed in the exact spot where once stood the statue of a monarch, further positing a debate between democratic values and those of a more hierarchical society. In the opening scenes, we see the old sculpture being removed by a crane, but a cock-up results in the statue coming loose and toppling awkwardly — as if it were one of those monuments to dictators that are periodically torn down on television by cheering, angry protesters. Who ultimately is responsible for order? And who measures equality?

Through a variety of episodes in Christian’s life and work, we see the failure of the kind of utopian thinking “The Square” represents. Is that what we’re seeing, though? Or is it the fact that Christian, as the successful and powerful head of a major art museum, cannot himself handle anything that smacks of genuine equality? Early on, we watch him walking to work on the street, amid dozens of other people. A woman runs, screaming for help, toward a nearby man, a stranger. Christian gets pulled into helping the woman, as he and the other man block a random angry dude from attacking her. Afterward, Christian and the other protective man congratulate each other and delight in the adrenaline rush of a good deed of physical bravery; the woman, meanwhile, is nowhere to be seen. Would these two have been so keen to help if the woman hadn’t prompted them to? Later scenes echoing this moment suggest that the answer might be no. And the fact that Christian realizes that his phone and wallet have gone missing immediately following the incident might mean that his supposed heroism was ultimately for naught.

Christian thinks of himself as a decent, fair-minded person. But his vision of himself is, as with all of us, selective. When he’s feeling good, he gives money to beggars; when he’s concerned and distracted, he ignores them. He’s a nice, fair-minded progressive in theory, but when less powerful people that he’s wronged confront him, he gets a “Why me?” look on his face. That Claes Bang manages to keep this man reasonably charming, even as the film interrogates his privilege and his very nature, is certainly some sort of achievement.

The Square is a film of set pieces, but perhaps the most impressive involves a museum gala dinner that is interrupted by a man pretending to be an ape (played by Terry Notary, the American stuntman and motion capture coordinator), whose antics at first seem entertaining and eventually become terrifying. The scene reiterates some of the key questions at the heart of The Square: When left to its own devices, does humanity find equilibrium or does it disintegrate into aggressors and subjects? And just what does it take for us to come to others’ aid? Where do we draw the line between the individual and society? The Square has a remarkably clearheaded and streamlined way of asking these many questions, but the answers it provides are always tantalizingly unclear.

BILGE EBIRI, The Village Voice, 23rd October 2017.

What you thought about The Square

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 (33%) | 18 (55%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 33 Film Score (0-5): 4.18 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

80 members and guests attended this screening and 33 of you were kind enough to give a response. This has delivered a hit rate of 41%.

As Bilge Ebiri wrote in his review of, ‘The Square’ in The Village Voice in 2017, ‘the beauty of the movie is that everybody will have their own ideas about what, exactly, it is saying’. Responses from our members certainly reflected this! “Thank you, as usual, for exposing us to the unusual!” said one reviewer, “Absolutely compelling. Great filming and a very valid explanation of societal values”, ‘Interesting and intense. Rather too long and drawn out in parts but interest was sustained despite the somewhat baffling plot”, “Totally absorbing”‘.

Many commented on the “Excellent direction and filming”. The constant change of scenes and scenarios caused one to comment, “At times hilarious, at times tense!”, “I felt I was being bounced from one scene to another – comic, weird, strange, bizarre”, “Interesting study in superficiality, reality, hypocrisy, simple pleasing etc. and how they interact”.

The film provoked much discussion, “What a cornucopia of wonderful scenes”, “Rambling exploitative, incoherent – profound nonsense about art”. “Intriguing and compelling, over-long”, “Too clever by half!”, “Raises more questions than answers! Challenging”. One reviewer found the film, “Serious stuff but very heavy going. Mannered camera work, disjointed plot ...”

Many enjoyed the humour in the film, “I found it more humorous than expected and its comments on “what is art “and “there is no such thing as bad publicity” was very apt”. Quite a few of you asked this question, “Why did the girl live with a gorilla?!” About the end of the film: “A bit depressingly true to some aspects of modern life – emotions shallow and people hiding behind meaningless strings of words!” ‘Why was The Square not mentioned in the end?”, “I was so confused at the end”.

Some of you really went into some depth about the film: “Ruben Östlund's film was thought provoking, peeling away the layers of civilised, societal norms to what lies beneath. Are we respectful of our fellow human beings, are we true to ourselves, and are we kind to all? "The Square" provides a frame around what we all believe is good (the plaque in the square), but what happens when we step inside or outside of it? The film gave me a lot to ponder. I came prepared to feel uncomfortable and decided to just feel it during those parts of the film - as its all part of being human. I also enjoyed the use of the camera, the music and the humour”. “The film was most enjoyable whilst also being challenging. It posed many questions to each of us about what we would do in the same circumstances for each of the many situations that the hapless Curator found himself in. For him, at least, it was a study in hypocrisy and, sadly, that is a human failing that we observe every day in our lives”.

“I found this film really weird and far too long. I think it could have been excellent if someone had edited it quite severely. Whilst I think I understood the concept of the film with regard to the sanctuary of trust and caring and its relationship to the real world this failed to come across. There were several bizarre scenes I did not understand at all particularly the „caveman" type appearance at the dinner party which went on too long. Having said that some parts of the film were delightful. It was lovely to see Elizabeth Moss away from her Handmaid role as Offred and I really enjoyed the condom scene. The Tourette's scene was also extremely funny and beautifully timed. The gorilla lent a breath of eccentricity and the baby stole the group discussion scene. The ridiculous pair dreaming up media events reminded me of the W1A BBC spoof discussions series. The hoovering up of the piles of earth installation was also very funny. Some years ago my husband and I saw a serious film about the National Gallery. It was about 3 hours long and included experts giving supposedly learned comment about the meaning behind famous paintings. We felt that many of their comments were over the top and should be debunked and this film reminded me of this”.

“Completely absorbing (I didn’t notice how long it was) – but is it Art? Starting off asking us about art and our reactions to it, it gradually morphed into a much less comfortable examination of our attitudes to others. Beautifully done. Treasured moments – the exhibit cleaner and the reaction to the problem. The unresolved transformation of the audience in the dinner sequence. The verbal tussle with Moss”.

“4/5 because it has made me think & talk about several different things that were themes in this extraordinary, if slightly overlong, film! I am not sure if I liked it or “got" it though, rather like much of the artworks in the X-Royal Museum! However, it is a film I am pleased to have seen. Acting was good, and for a second film in a row, the children were so believable too”.

“A difficult film to respond to succinctly; but technically excellent, cinematography and sound. A fascinating portrait, used by the director to make us question ourselves and our own values. But I was reminded of those old John Cleese management films about how NOT to do it - every story thread turned out a disaster for eminently foreseeable reasons - even W1A was in there somewhere. Really well made and thought-provoking, and thoroughly enjoyable. Excellent”.

“Immediately after viewing – Poor. Just one day later - Good. Watching was a painful experience, 2.5 hours in an excruciating spiral of personal and social embarrassment. But what a lot to ponder. I am sure I will remember this film for far longer and more vividly than many of the films I have actually enjoyed watching. How odd is cinema. But he needs an editor. The family stuff with the two daughters was gruesome and didn't seem to add much to our understanding of the main unravelling character”.

“I would rate it 4.8 out of 5. Land of Mine is still my favourite! I have thought about it a lot since the screening - a sure sign that a movie was worth watching. For most of the time it seemed like we were actually inside a conceptual art installation at a museum or gallery and, as often happens with me and conceptual art, I left wondering if I had really ‘got it’. During the middle third I found myself feeling irritated and frustrated but I’m not sure why. It might have been the pace at that point or me feeling that I wasn’t ‘getting it’ or me just getting frustrated because it was too ‘artsy’ at that point. I think that was one of the points of the film - to lampoon the Art world and in particular the alpha male types who bestride it. I appreciated the humour and thought the fund-raising dinner was a magnificent piece of theatre. I’m guessing the scene where Christian climbs the staircase, which from above looks like concentric squares, was a metaphor for him finally (or fleetingly?) entering that space of 'trust and caring’? “