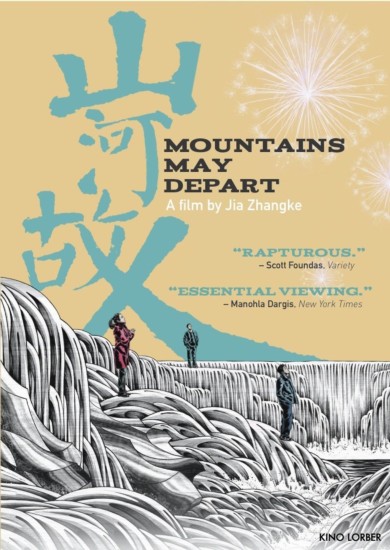

Mountains May Depart (Shan he gu ren)

China’s obsession with material goods is explored across three different time periods: 1999, 2014, and 2025. Childhood friends Liangzi and Zhang are both in love with Tao who eventually decides to marry the wealthier Zhang.

Film Notes

Mountains May Depart review: Jia Zhangke scales new heights with futurist drama

Jia Zhangke’s Mountains May Depart is a mysterious and in its way staggeringly ambitious piece of work from a film-maker whose creativity is evolving before our eyes. It starts by resembling a classic studio picture from Hollywood, the sort of thing George Stevens or Douglas Sirk might have made, or perhaps something like Mu Fei’s Chinese classic Spring In A Small Town. Then it morphs into a futurist essay on China’s global diaspora and its dark destiny of emotional and cultural alienation. In this movie, the boundaries are getting pushed, visibly, between the opening and closing credits. The pure work-in-progress energy of all this is exhilarating, and if the resulting movie is flawed in its final act, then this is a flaw born of Jia’s heroic refusal to be content making the same sort of movie, and his insistence on trying to do something new with cinema and with storytelling.

His movie is split into three parts, taking place in 1999, in 2014 and in 2025. We begin with a bunch of people dancing to the Pet Shop Boys’ Go West, and as the new century and millennium dawns, the movie shows China more or less obsessed with doing that: going West, embracing capitalism while at the same retaining the monolithic state structures of the past, and beginning to worship consumer goods as status symbols: stereos, cars, and perhaps most importantly mobile phones — a technology which the film shows retaining its fetishistic power for the next quarter-century.

Jia’s longtime collaborator and wife Zhao Tao gives a superb performance as Tao, a young woman who is dating a coal-miner Liang (Liang Jingdong). But Tao is also being courted by the impossibly conceited Jingsheng (Zhang Yi), one of China’s new breed of pushy entrepreneurs who actually buys the coalmine, forces Liang out of the picture, and marries Tao. They later have a child that Jingsheng in a grotesquely celebratory mood insists on naming “Dollar”, so great is his belief in the child symbolising a prosperous quasi-Western future. Meanwhile, the devastated Liang moves away but later in 2014, they are all to meet again and later in 2025, when Dollar is a twentysomething college dropout in Australia, his life appears to have absorbed a genetic destiny of alienation and pain.

Zhao Tao begins the movie as a girlish, ingenuous soul: always bouncing happily around, treating both her suitors with a kind of frank, sisterly affection while she internally ponders the question of love and marriage. When this becomes a more insistent reality, she appears to grow up emotionally on camera: deeply affected by how wounded Liang is by his romantic defeat. She becomes a beautiful, but melancholy woman in the light of her own marital disaster, and then her sadness assumes a tragic dimension in the wretchedness she experiences after her beloved father dies, and sees how her own son has been encouraged by her ex-husband to think of her feelings and her family as irrelevant. And finally all this is reconfigured in Jia’s almost sci-fi sketch of the future, incarnated in the form of Dollar who appears to have forgotten his mother and his mother country. But he experiences the return of the repressed.

It is extraordinary to think how Jia Zhangke’s film-making has changed since his early, more opaque movies like Platform (2000) or Unknown Pleasures (2002). Now the performances he is getting are far more emotionally demonstrative. This is not a violent movie like A Touch of Sin (2013), his satirical adventure in Tarantinoesque pulp: but it has a shockingly violent moment when someone gets punched in the face. Yet it also has a bewilderingly surreal moment when Tao witnesses a light aircraft crashing next the road down which she is walking, yet without reacting or calling for help. Did she dream it? Did Tao, in fact, dream the movie’s entire final Australian section? Jia allows us, fleetingly, to suspect this.

That final coda does not entirely work: inevitably, some of the dreamed-up technological innovations and stylings look self-conscious and the sheer weirdness means that the emotional power of ordinary life is no longer available. And yet without this unexpected leap into the future, the movie would not have the savour that it has. And what a wonderful performance from Zhao Tao.

Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian, Cannes 20th May 2015.

Three times in “Mountains May Depart,” the latest from the transformative Chinese director Jia Zhangke, people stand near a river that weaves through the landscape like a snake. In the first instance, three friends light fireworks that send out modest sparks. In the second, only two return to the river, where they ignite a bundle of dynamite. By the third trip, only one of the original three remains, everyone’s life having changed as profoundly as China, a cataclysm that’s expressed by a series of rapid explosions in the river, suggesting a drowning world.

Few filmmakers working today look as deeply at the changing world as Mr. Jia does, or make the human stakes as vivid. The three sending out those sparks are Tao (Zhao Tao), and her two close male friends, Zhang Jinsheng (Zhang Yi) and Liangzi (Liang Jin Dong). An affable, easygoing drifter with an expansive smile, Tao works in a small store in the city of Fenyang (Mr. Jia’s birthplace). Mr. Jia likes a slow reveal and it isn’t initially obvious that Tao is the movie’s emotional organizing principle whose feelings run, surge and erupt. The story tracks Tao and her relations with both Liangzi, who works at a coal mine, and Jinsheng, a budding entrepreneur.

Eventually, Tao chooses one man over the other, a decision that fractures the trio and sends the narrative spiraling in different directions. Mr. Jia’s approach means that you have to do a certain amount of interpretive work, though mostly you just have to pay attention and be a little patient. If you do, you will notice that “Mountains May Depart” is a movie of threes: its main characters, moments in time, narrative sections, historical symbols and even aspect ratio come in triplicate. This schematic quality isn’t necessarily obvious on first viewing, even though the story’s time frames — 1999, 2014 and 2025 — are announced on-screen and accompanied by a corresponding increase in the size of the image, an enlargement that mirrors the character’s expanding universe.

When the movie opens in 1999, for instance, Tao is right in middle of the action (and the frame), dancing with a large group to the Pet Shop Boys’ dementedly catchy 1993 cover of “Go West,” an old Village People tune. The original music video for the Pet Shop Boys’ version, an exuberantly surreal pageant, includes shots of Red Square and Vladimir Lenin. Mr. Jia doesn’t reference the video, but it’s likely he used the cover partly because of its post-Soviet bloc resonance. Whatever the case, it’s a lovely, festive scene that suggests that everyone is in a party (or Party) mood. When Tao and the others form a conga line it seems as if they have decided to take the song literally:

Together, we will go our way

Together, we will leave someday

Together, your hand in my hands

Together, we will make our plans

Mr. Jia never over-explains his work. The dance feels triumphant, at once choreographed and spontaneous, but there’s no immediate reason for it, even when the date 1999 appears on-screen. It isn’t until the next scene, when Tao is trading New Year’s greetings, that the dance feels tethered to a rationale. By that point, though, you will have had time to think about the dance, to turn it around in your head, consider its possibilities and wonder whether the revelers are spontaneously dancing or celebrating the end of the millennium or the 50th anniversary of the People’s Republic. Or perhaps the scene has more to do with Tao, a woman who smiles and who dances.

Ambiguity is a defining characteristic of the European art cinema; at its most clichéd, directorial solipsism is mistaken for mystery and empty images are turned into endlessly masticated cud for cultists. Although Mr. Jia is obviously conversant with the European art film — and East Asian cinema and Hollywood and so forth — he has carved out his own ways of making cinematic meaning, an approach that draws on different idioms and traditions. He occasionally folds an image into the mix that can feel enigmatic, but that over time make sense when considered in the context of the movie as a whole. A shot of an old-fashioned pagoda may not make ready sense, may even look like picture-postcard scenery, yet by the end of the movie it may make you weep.

Mr. Jia has characterized “Mountains May Depart” as his most emotional movie, which may underplay how deeply moving his work can be. While he invariably addresses larger cultural, social and political issues, sometimes openly, at other times obliquely, what makes his work memorable is how those larger forces are etched in the faces and bodies of his characters, in the coal dust that defines one man’s reality — and, by extension, one China — and the hard mask that defines another truth, another China. Here, when Tao first walks down a street flanked by modest brick buildings, she is moving through a country that is rapidly being lost to what’s optimistically called development. By the end, she is living in a new world even if, Mr. Jia suggests, her soul remains in the old.

Manohla Dargis. The New York Times, 11th Feb 2016.

What you thought about Mountains May Depart (Shan he gu ren)

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 (28%) | 28 (52%) | 9 (17%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 54 Film Score (0-5): 4.04 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

99 members and guests attended the screening with 54 providing a comment, a 55% response rate. Your erudition came into its own this week and is reflected in the fact that I have transcribed all of your comments on to three A4 pages!

“Was not sure if I was watching Oedipus rex re cast, a national allegory, or a futuristic fiction movie but came to the conclusion it was all three within a stylized romantic melodrama. Did think this was extraordinarily beautiful film with lush, rich cinematography. The barely veiled attack on Chinese capitalism has a resonance set against the immigrant experience. While stereotypes often fall down, Jingsheng doesn't; we understand that China's growth in allowing rampant personal wealth comes at the cost of a well-established culture. Set with the themes of loss, emptiness, and alienation from family and tradition, the film's three parts are stylistically disparate, but connected by several motifs, including a lachrymose Cantopop ballad, a man who carries a traditional sword, and Tao's dog. So what happens in the subtropical Tomorrowland? Expat Chinese youth learn about their native culture from a Hong Kong-bred older woman who succeeds in eliciting feelings long buried about Dollar's mother. Loved Zhao Tao's performance; measured sincere and moving behind the smiling but also bitter angry and almost unforgiving of Dollar. Liked the blatant 'Go West' at the start and finish; ironic?”

“Thank you for showing the Mountains May Depart film last evening. The locations of the film were interesting to note the changes of the scenery during the different period phases of the film and how some parts of China especially have created new infrastructure. The storylines had potential but it was sad that there were no finales on what happened to Liang after receiving funds from Tao. How did Tao’s life move forward after her father’s funeral and did her son, Dollar ever go home to her? Also did Jingsheng become a recluse in Australia? The film focused chiefly on the character of Jingsheng being a narcissist”.

“Thought provoking. I had trouble understanding the English language dialogue”. “A little slow to start with amazing acting”. “Interesting film which was unpredictable and well-acted. Could have done with a stronger plot and a few loose ends never got tied up. What happened to Liang?” “A bit long winded. A lot of unresolved story strands”. “Creative script. Some great shots and quiet moments. Good film choice. Thank you”. “Interesting if rather disjointed story line. Unique movie”. “I warmed to it but found it a bit disjointed. Laboured script”. “A little puzzling at times – the plane crash?? And the jumper motif? But interesting and well performed and filmed. Probably missed a few cultural references!” “Wonderful insight into contrasting times in China”. “Too much naval gazing”. “Interesting. Good acting. Insight into Chinese life and culture”. “Powerful and moving narrative and characters. General strong structure and directing. Very good casting”. “And so life goes on”.

“Thanks again for your efforts in bringing films to us all that we would not otherwise encounter. With regard to this film, I can't decide if it's really clever or mediocre. I loved the opening but found most of the first part rather plodding and wasn't at all convinced by the love triangle. In Peter Bradshaw's review he says "Tao internally ponders the question of love and marriage" but I never got the feeling that there was much deep thinking going on because the characters were so one-dimensional. The only person who seemed to raise doubts about Tao marrying Jinsheng was her father. Tao seemed to be a passenger in all the decisions she made about her love, marriage, her son and then later Liangzi. I just couldn't warm to any of the main characters. I wish the father had had a bigger part - he could have glued it all together. I was actually a bit relieved when the film appeared to be over half way through (when "A film by Jia Zhangke" came up on the screen). The second half was better but muddled and I didn't buy the argument that the son didn't speak any Mandarin. He would surely have picked it up from his father and been bilingual even if he'd spent a good deal of time away at International School. But I guess there must be examples of these kind of kids otherwise they wouldn't have been represented in the film. And I'm not sure what the point of sexualising the relationship with his teacher was about - that seemed like a red herring. But, I thought the main messages were interesting and the contrast between dirt poor and super rich, as illustrated by the squalid hutongs and luxurious modern apartments, rang true. It could be that I am being dense in not able to recognise the brilliance of this film but I had the feeling that someone had taken a hatchet to it during editing and mistakenly cut out some important connective tissue”.

“The first two thirds of this film are a cinematic masterpiece; graceful, economic storytelling, the design and framing are faultless, a lean script and an amusing off kilter style that is redolent equally of classical myth and Shakespeare but also the gnomic dialogue of Hal Hartley, layered story building of the 'Love & Rockets' graphic novels, with occasional Lynchian violence. The spare narrative is a much cleaner and more affecting vision of ageing and the painful acquisition of wisdom than 'A Late Quartet'. In the last section however a visual narrative is swapped for dialogue and exposition. Possibly this is intentional and meant to reflect the unsettled, rootless feel of those lost abroad. It is not as effective and feels uneven and half realised, thus the film finishes somewhat unsatisfyingly. Overall still great though”.

“I thought Mountains may Depart was very good, almost excellent. It gave a compelling view of Chinese rural life and it difficulties and a fascinating glimpse of the tensions between parents and children when the latter are educated in a different culture. The longing of the long term expatriate for the motherland was also well described”.

“I liked it! I was beautifully shot, and full of subtle touches like using 4x3 for the earlier sequences, then widescreen for the later ones; I liked the portrayal of the future - only a little way (2025), and entirely recognisable and believable. Some of it was jumpy, and there were strands that were just abandoned unresolved (what happened to the miner in the end?), but the acting was mainly excellent, and I'd give it 4 out of 5 at least”.

“I kept finding in Jonathan Romney’s review on Film Comment https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/film-of-the-week-mountains-may-depart/ the thoughts that I couldn’t express as clearly. When faced with something that sounds corny or doesn’t make sense (and there was plenty here), I’m inclined to think that it’s down to my lack of knowledge or insight. Which led me (along with Michael’s introduction) to suggest that GFS could usefully offer tutorials on some of the films that are shown, to discuss these elements and explain (with clips) the references and reflections that are clearly an integral part of understanding film. How about it GFS, one or twice a year on a suitably selected film from the season?”

“Bleak and depressing. So many “damaged” people. Found the English dialogue mostly incomprehensible. Something and nothing. Too edited”. “Enjoyable film”. “A bit slow. Rather disappointing”. “What was it about?” “A little slow”. “Naïve, slow but utterly compelling. Very rare for me to mark as Excellent”. “Good settings. Made China look as bleak as I thought it was”.

“Well shot – but a bit slow moving. I don’t wish to ever visit China!” “Would like to see more from this Director”. “How unexpectedly brilliant. So much to think and talk about. Such a carefully crafted film. Thank you”. “Very good acting. Nor sure I caught all the nuances”. “Too drawn out”. “Some good moments but I’m afraid not my favourite! Go West tum to tum tum tum!!” “Fascinating film. Wonderful performances from the lead actress”. “A bit long and drawn out but otherwise very engaging”. “Tragic story – did not like all the loose ends of the two stories. Well-acted”.