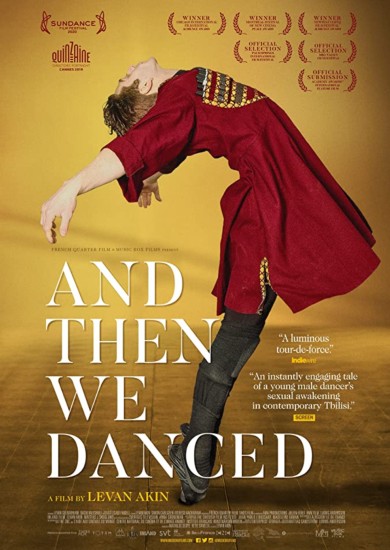

And Then We Danced

A passionate coming-of-age tale set amidst the conservative confines of modern Tbilisi, the film follows Merab, a competitive dancer who is thrown off balance by the arrival of Irakli, a fellow male dancer with a rebellious streak.

Film Notes

And Then We Danced review – heady tale of forbidden desire

Tbilisi is the setting for this charged romance between two men training as traditional Georgian dancers.

Real-life dancer Levan Gelbakhiani is Mehrab, a redhead with round, watchful eyes training as part of the National Georgian Ensemble in Tbilisi. It’s in his blood – his delinquent older brother David (Giorgi Tsereteli) is a dancer too, as were his parents and ageing grandmother. A macho discipline that comprises forceful military moves and elaborate, athletic leaps, the tradition of Georgian dancing contains “no room for weakness” and certainly “no sex”, according to Mehrab’s teacher. Enter new student Irakli (Bachi Valishvili), tall, dark and handsome with a twinkle in his eye and a spring in his step that knocks Mehrab sideways. Swedish writer-director Levan Akin’s heady third feature is attuned to the way desire has a tendency to throw everyday mundanities into sharp relief.

Mehrab is indifferent when dance partner Mary (Ana Javakishvili) falls asleep on his shoulder, but when it’s Irakli, he’s silently elated. Most of the boys’ increasingly charged interactions play out in the studio before the sun has risen, and after hours, over a lamp’s orange glow; cinematographer Lisabi Fridell bathes their blooming attraction in syrupy amber light. A street lamp illuminates a private show and turns it gold, as Mehrab dances shirtless for Irakli to Robyn’s seductive track Honey. This awakening eventually leads him to one of Tbilisi’s underground gay clubs. Gelbakhiani is commanding in his first acting role, metabolising heartbreak and moving with an irrepressible prowling sensuality.

In ultra-conservative Georgia, desire between two men remains strictly taboo. And so longing throbs like a sickness in small, unacknowledged gestures like the careful folding of a would-be lover’s T-shirt or a juicy, bleeding pomegranate (recalling, perhaps, Call Me By Your Name’s peach). Luca Guadagnino’s queer romance might seem like a reference point, but that film’s swanky Italian villa is a world away from Mehrab’s, with his precarious restaurant job and out-of-credit mobile phone. Here, the stakes are higher, and so the romance sweeter.

Simran Hans, The Observer, 14th March 2020.

And Then We Danced review: Georgian LGBT+ drama is giddy with the pleasures of first love.

Levan Akin’s film, set and shot in the capital of Tbilisi, argues that joy itself can be a form of radical defiance.

Georgian dance is all fire and fury. Percussion plays – sparse and low – as lines of men swing their limbs back and forth like they’re trying to whip up a tempest. The women are slower, and more graceful. Dressed in floor-length tunics, they take tiny steps, creating the illusion that they’re floating.

Merab is a dance student at the National Georgian Ensemble, a young man with a sharp jaw and wide, hungry eyes, here played superbly by Levan Gelbakhiani, superb. Tradition runs in Merab’s blood. His parents, now separated, were once dancers, but have become stagnant and bitter. He’s danced with the same partner, Mary (Ana Javakishvili), for years – the two are a kind of de facto couple – and spends his nights working at a local restaurant. His brother David (Giorgi Tsereteli) also takes classes, but his fondness for mid-week benders means he rarely shows up. And so everyone turns to Merab for support. The pressure has made his body taut and fragile.

His rigidly constructed world soon starts to crumble after the arrival of a new dancer, Irakli (Bachi Valishvili). This stranger moves with confidence. He’s muscular but light in his step, with open features and an easy smile. Merab treats him as both a challenger and an object of fascination. Desire swiftly takes over.

“There is no sex in Georgian dance,” his instructor (Kakha Gogidze) warns. But when Irakli gently places his hand on Merab’s thigh, in order to correct his posture, it’s immediately charged with erotic thrill. Levan Akin’s And Then We Danced is giddy with the pleasures of first love – how it pulsates through the body and mind. It’s in the way Merab habitually chews on his crucifix necklace or takes a covert sniff of Irakli’s shirt.

Homosexuality isn’t outlawed in Georgia, but the country remains in the stranglehold of conservatism. The women gossip about a dancer in the main ensemble who was kicked out for being gay. His family sent him off to a monastery “to make him normal again”. Akin (who was born in Sweden to Georgian parents) has spoken about his struggles shooting the film in the country’s capital, Tbilisi. He often had to lie about the films content in order to secure locations. Troops had to be stationed at the film’s few Georgian screenings, after ultra-conservative and pro-Russian protestors swarmed outside of the cinema.

Akin’s film argues that joy can itself be a form of radical defiance. Merab’s story isn’t just about the pangs of desire, but the slow untethering from tradition’s pressures and expectations. At first, he’s desperate to heed his dance instructor’s warnings that his posture isn’t “hard as a nail”. But he soon begins to explore his identity and his sexuality through movement: whether he’s out celebrating in the streets, partying to ABBA, or seducing Irakli to Robyn’s “Honey”. To Merab, those dances are an act of reclamation. The future belongs to him – and all those who dare to live free.

Clarisse Loughrey, The Independent, 12th March 2020.

What you thought about And Then We Danced

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 (16%) | 15 (60%) | 6 (24%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 25 Film Score (0-5): 3.92 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

According to our stats there were 106 Sessions and 76 Users logged in to watch. This means that 76 were successful in seeing the whole film. if you are still struggling to log on please let us know.

As you can see 25 members left a star or a comment. Please let us know what you think.

“I enjoyed this film both for its tale of a young person's developing awareness of who they are and again for an insight into a country and culture about which I knew very little. The actors portrayed believable people. Thank you for another interesting film”.

“My wife and I watched this and found it a little bit old hat, covering ground often visited in recent films (Call me by your name). I read Michael O'Sullivan's introductory talk (for which many thanks) the day after. This provided most informative context and changed my view and score. Our one visit to Tbilisi was almost 50 years ago and it would seem that its machismo culture is still alive and well. I liked the dancing and I thought the drumming was absolutely tremendous. As for the sex, I have reached an age where I prefer the director to shift it as soon as possible off screen (irrespective of the sexual choices of the participants)”.

“Like Georgian dance this is a form we recognise but has a style all its own. On the face of it it's a coming of age picture of a familiar kind but of a more acerbic and dramatic variety than Hollywood would favour. In the end the protagonist is betrayed repeatedly but does not get his revenge. Neither does he get the girl ...or boy. There is a refreshing sharpness to its emotional realism that contrasts to the warm fuzzies of say 'Billy Elliot' but the fact that Merat's defiance converts no-one other than the patient and good hearted Mary makes for a refreshing and realistic finale”.

“Beautiful dancing and atmospheric photography”.

“The empathy, honesty and exuberance that And Then We Danced makes the gay coming-of-age story an intriguing watch showing how just portraying members of a marginalized group can be a radical act. Thought the last dance audition as the finale was a metaphor for a young man finally losing the weight of what is 'traditional' and expected; Georgia's straight culture is evidently toxic, as shown throughout. Liked the contrasts set by the dance scenes, energetic and flexible against the authoritarian directions of instructor, re-enforced by him saying "there is no room for weakness in Georgian dance as it's based on masculinity", which made Merab all the stronger. Traditional Georgian dance is masculine and Merab is too soft. 'You should be like a nail.' Camera develops the simmering sexual tension as the two dancers' bodies grow closer. Liked Irakli's wearing of an earring early on! Evidently the film is pretty courageous as well as a thoughtful reflection of Georgian identity, while trying to reclaim it in a more progressive manner. Strong well measured performances by so many of the handsome cast, but particularly the younger actors, camera direction emphasised the personal so well. Thanks for showing it and highlighting a difficult, but significant, struggle”.

“Stunning performance by the young actor playing Merab. And the cinematography was also stunning. An insight into Georgian culture and society - and what a fascinating language! Well worth the watch.”

“This was a very special film, with an amazing back story of its production and its release, both in Georgia and elsewhere. Huge difficulties had to be overcome to complete it. The performance of the main character, given his lack of acting experience, was astounding and the film portrayed very clearly the cultural and generational discrimination against homosexuality, although not policed so thoroughly that there is not room for an openly gay club in Tbilisi! It was a pity that the subtitles did not extend to the songs for I feel that these Georgian folks songs must have been chosen because they were very relevant to the action. So much of it was good and yet it failed to capture me - I always felt outside looking in rather than involved”.