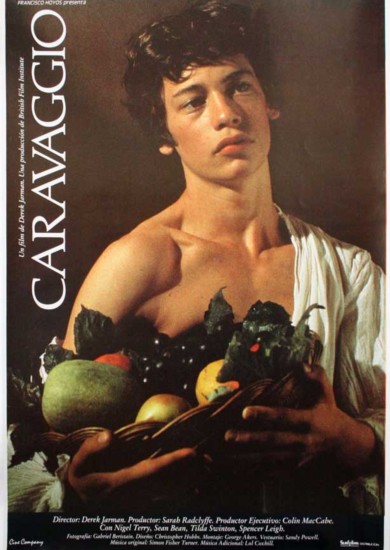

Caravaggio

This fictionalized biopic brings Caravaggio's works onto the screen, telling a story of what might be termed transgressive art by a “transgressionist” director (Derek Jarman film). This was also Tilda Swinton’s film debut.

Film Notes

As with his earlier film, Sebastiane (co-d. Paul Humfress, 1976), Jarman is interested in how "man's character is his fate" in his meditative portrait of the Renaissance painter Michelangelo Caravaggio (1573-1610). His treatment relies less on naturalism than on an attempt to visualise the world as Caravaggio saw it. The chiaroscuro of the period is so well delivered that often the staged scenes appear at first to be Renaissance portraits.

The young Caravaggio, played with impish sensuality by Dexter Fletcher, sells his work and his body and gives himself over to Bacchus: "I took on his fate, a wild orgiastic dismemberment". Patronage from a cardinal allows the artist to live well and learn how to "repeat an old truth in a new language".

The film cuts between the older Caravaggio (Nigel Terry) on his death bed and earlier episodes of his life, knitted together with a poetic voice-over which articulates the artist's struggle with doubt and how to invest art with the passion of lived experience. It is clear that Jarman himself wrestled with these elements, and the film is most successful when he captures the tension between emotional reality and the creative representation of it. Many scenes linger on the patience art demands, showing the artist waiting for the canvas to breathe life into his subjects.

The dramatic intensity of lived experience threatens to overtake Caravaggio when he meets the young brawler, Ranuccio (played with Cockney relish by Sean Bean) and his lover, Lena (one of Tilda Swinton's best performances for Jarman). A messy love triangle ensues and Caravaggio is wounded rather symbolically in the side by Ranuccio in a fight. Jarman's anachronistic elements, such as the sound of a train, a typewriter, a magazine, keep the themes eternal rather than historical, and add another texture of the lived experience Jarman brings to his artistic practice.

Jarman's love of ritual finds full expression in the elaborate enactments of Catholic ceremony upon Caravaggio's death and the final scene suggests that the artist as a young boy found his vocation upon seeing a performance of the Passion. Some may find the parallel between Christ and Caravaggio heavy-handed, but the film grapples ardently with the portrayal of an artist's life in ways that must have inspired films such as Love is the Devil (1998), John Maybury's portrait of Francis Bacon and Looking for Langston (1989), Isaac Julien's meditation on Langston Hughes.

Cherry Smyth, BFI online.

"Caravaggio," which is less a movie than an act of vandalism, narrates the life of the influential late-Renaissance painter through the lens of an imagined sexual obsession and an assortment of modernistic effects.

In the hands of writer-director Derek Jarman, Caravaggio (Nigel Terry) is a thrill-seeker, a bisexual voluptuary who discovers the object of his desire, Ranuccio (Sean Bean), in a bare-knuckles boxing match, and quickly falls into a me'nage a` trois with the brute and his girlfriend Lena (Tilda Swinton). He paints. He loves. He fights. He murders. And he dies throughout, for "Caravaggio," with rather pointless confusion, is told as a flashback from the artist's deathbed.

I may be a dull fellow, but from the very beginning of "Caravaggio," I hadn't the slightest idea as to what Jarman was up to. The movie, for example, is full of anachronistic effects -- courtiers in doublets pounding away at upright typewriters, an automobile in a barn, the thunder and whistles of distant trains, and an absurd sequence that seems to take place in a New York nightclub.

What's most puzzling is Jarman's view of Caravaggio himself. Throughout, the artist talks in voice-over, a jumble bizarrely composed of overheated poesy, homoerotic dreams and the kind of "insights" that might inspire a sophomore at Bennington to scribble in the paperback margin, "|" or even "|||" Thus: "Man's character is his fate"; "The gods have become diseases"; "All art is against lived experience"; "I am trapped, pure spirit in matter ..."

Does Jarman want us to hoot at Caravaggio, in the same way that the artist himself (played as a young man by Dexter Fletcher) sneers at his similarly orotund patron, the Cardinal (Michael Gough)? Or are we supposed to marvel that such great art flowed from such a silly soul (the idea at the heart of the similarly banal, but infinitely more entertaining, "Amadeus")?

At any rate, you spend less time wondering what Jarman is saying than wondering when "Caravaggio" is going to end. A former painter, costume designer and set decorator, Jarman has a routinely tasteful sense of handsome compositions, but there isn't a shot in the movie that makes you sit up and take notice. His cloddishness makes you see "Caravaggio" less as a tribute than some odd, and oddly irritating, effort at assassination.

Paul Attanasio, Washington Post, October 23 1986.

Patrons of the National Gallery's Caravaggio exhibition shouldn't expect to obtain scrupulous biographical information in this opportunist re-release of Derek Jarman's 1986 treatment of the celebrated painter. Instead, Jarman builds on the unquestionable homoerotic charge in Caravaggio's work to speculate on the artist's relationship with his models - especially with hunky Ranuccio (Sean Bean), whose well-toned physique is supposedly captured in The Martyrdom of St Matthew, and who becomes the centre of a vicious love triangle involving his wife (Tilda Swinton) as well as the artist.

Purely on cinematic terms, Jarman's film is bit of a curate's egg. Arguably the most accessible of his films, it remains a testament to his distinctive visual style. Taking a leaf out of Pasolini's book, Jarman jettisons period authenticity in favour of highly aestheticised spaces, filled with beautifully composed and lit pictorial tableaux. The theatrical acting and dialogue, as well as the occasional token anachronism - designed to emphasise the artificiality of it all - only succeeds in patches, and occasionally verges on the ridiculous.

But there's a genuine, haunting power to Jarman's film, which feels somehow like a valedictory letter from a distant era - the pre-Aids 1980s, when Jarman's high-minded camp seemed to be the future of art cinema. Jarman's highly-publicised announcement that he was HIV-positive came shortly after Caravaggio's release, and his own work took a decisively political turn in consequence.

Andrew Pulver, The Guardian, 11th March 2005.

What you thought about Caravaggio

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 (20%) | 4 (20%) | 8 (40%) | 2 (10%) | 2 (10%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 20 Film Score (0-5): 3.30 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

60 members logged onto our streaming service to watch Caravaggio.

Judging by the responses only a few of you left the screening with positive thoughts.

I am afraid the film registers the least popular of the season so far.

Here are the comments collated from the website.

“Felt the film captured Caravaggio's twisted genius, his brutality, bisexuality, passion and a transcendent vision, which elevated the common poor street beggar to the level of saint and angel. Was psychopathology evident? Thought the non-linear structure re-enforced the segmented nature of the film well. Beautifully lit, vibrant with colour, and carefully, if minimally, designed. Caravaggio was known for using things that did not fit with his day, including Biblical figures in a painting from his own time. So why be surprised by calculators, typewriters and cars? The film seems to be told in the moments of Caravaggio dying as he starts to see visions of himself as a child, as a young man, with Lena and Ranuccio etc. But ultimately, Caravaggio must die. Pretty profound, unsettling - darkly shadowed, specks of light and shadow fluttering in hidden places and the entire film actually looks like Caravaggio himself painted it. Liked Tilda Swinton's performance, as well as the understated Michael Gough”.

“Like the Washington Post I didn't see what Jarman was trying to do. I would have loved to have gained some understanding of Caravaggio's painting but film didn't help in this at all. While there were some good performances and interesting production design they did not remotely compensate for a chaotic and frankly boring film. The anachronisms were simply pointless and a distraction. It was self-indulgent and made me think that, in comparison, Ken Russell's later biopics weren't so bad after all!”

“I was looking forward to this film having followed several art history courses over lockdown and wishing to learn more about this colourful character. Sadly I felt that overall the production was very disappointing. I grew up in the days of Ken Russell's films and so am used to unorthodox approaches to the lives of great artists of all genres. However, I found the occasional oblique forays into the modern world to be ridiculous and did not feel they added anything to the film. I turned to various reviews whilst watching the film to see if I was possibly missing something. I understand that the backgrounds to the various scenes were based on famous paintings by Caravaggio but I did not find these particularly impressive. Also scenes of the artist actually working on paintings seemed unconvincing with dabbing’s of what appeared to be a completely dry brush in the same area of the canvas. There was a strange scene with an actress engaging in some demanding yoga poses which again did not seem to add anything to our understanding of Caravaggio. I would rather have seen a well-made documentary about his life with an expert explaining some of his techniques and visits to the places he lived in. I found the interior shots very claustrophobic especially in this time when we are all locked down in our houses. So overall I did not enjoy this film”.

“Have to agree with Paul Attanasio's views. I found it too confusing, very self-indulgent but predictably visually stunning”

“Visually luscious. I didn't follow half of it, but Derek Jarman's quirks and the light made up for that”.

“Paul Attanasio nailed it. Good to look at but impossible to love”.

“Felt stifled within the stage set of this film yet it highlighted the fascinating faces that were so well lit, as well as the sumptuous Renaissance colours and tableau. Indeterminable however and I have to admit that I had to force myself to watch it to the end”.