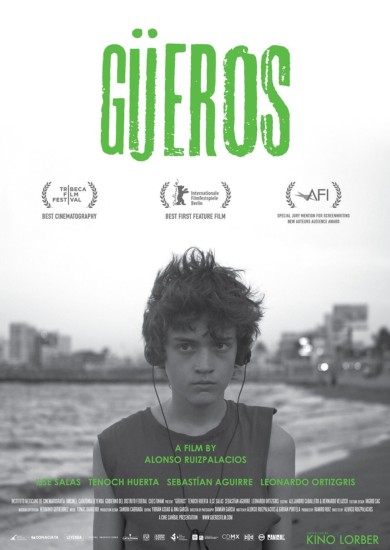

Güeros

In this black and white offbeat comedy, teenager Tomás is sent by his mother to live with his older brother in Mexico City where he hangs out with other “slacker” youths.

Film Notes

Right off the bat, Alonso Ruizpalacios’ “Güeros” captures three superlatives from this reviewer: Best debut feature I’ve seen in the last year, best Mexican film in recent memory, and best (black and white) cinematography since Pawel Pawlikowski’s equally stunning but very different “Ida.”

Lauded at numerous international film festivals since it debuted last year at Berlin (where it won Best First Feature), the offbeat comedy might also be called the most creative recent engagement with the cinematic past, especially the French New Wave, but that’s a subject that deserves both explication and rumination, so let’s start with the basics.

The year is 1999. Tomás (Sebastián Aguirre) is a teenage troublemaker who lives in Veracruz with his mother, whom he’s driving crazy. One day, when he drops a water bomb off a roof and it hits a harried woman and her baby, mom decides she can’t take it any more and sends the boy to stay with his older brother, Federico, a.k.a. Sombra (Tenoch Huerta), a college student in Mexico City.

“Güeros” is a film of running jokes, and one concerns the siblings’ skin colors. The word “güeros,” a derogatory slang term meaning something like “paleface” or “whitey,” applies to fair-skinned Tomás. Sombra (the nickname means “shade”) is dark, meanwhile. That practically everyone they meet seems to remark on this difference is never explained, but that somehow makes it ever droller.

When Tomás arrives in Mexico City, he finds his bro holed up in his incredibly filthy high-rise dorm room with his roommate and partner in slackerdom Santos (Leonardo Ortizgris). At night, they live by candlelight, if that, because there’s no electricity. Daytime, they sometimes cadge power via a cord supplied by their downstairs neighbors’ mentally challenged daughter.

Santos and Sombra are nominally students, but they’re not in class because their school is on strike. So why aren’t they out demonstrating? “We’re on strike from the strike,” they explain. In other words, they’re completely inert and disengaged, living on fumes and not interested in doing otherwise.

Ironically, it’s the arrival of young screw-up Tomás that injects some motion into their lives. The boy idolizes a legendary Mexican rock’n’roll pioneer named Epigmeneo Cruz (Alfonso Charpener), whose music he listens to on a battered cassette handed down from his and Sombra’s absent father. When Tomás learns that Cruz is reportedly near death at a hospital in the city, he persuades Sombra and Santos that they must find him and pay their final respects.

That, plus the fact that their downstairs neighbor wants to beat their asses for stealing his power, propels the guys out onto the highway in their shitty clunker, on an odyssey that takes them through many cul de sacs and wrong turns but also includes a stop at their embattled university.

Here, the film’s desultory pacing and whimsical mood give way to something much more electrifying: a university in the tumult of revolution. The situation is both dramatically and thematically important, so it’s worth quoting Ruizpalacios’ words on it.

“In April 1999,” he wrote, “the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) students began to strike to show their disagreement with the administration’s decision to instate an enrollment fee even though the University had always been free….What started as a symbol of dissidence (it turned out to be the biggest movement since the 1968 student strikes) finished as an existential crisis for many involved. Before long, social disparities began to surface within the student movement, causing distance between people who were involved. A lot people found themselves not only without a university, but without a purpose in life, no beliefs, nowhere to belong.

“’Güeros,’” he continued, “is actually two movies in one. On one hand, it is a portrait of this particular stage in Mexico’s history. On the other…it is an exploration of Mexican youth who are not able to feel at ease in their own country.”

This double purpose is a fascinating concept on the thematic level, and it has a corollary on the formal level that gives the film’s specifically Mexican social and historical concerns a universal cinematic reach. For, just as the story implicitly looks from the student activism of the moment (particularly related to the disappearance of 43 students in Guerrero state last year) back toward the ‘60s brand via 1999 (when issues of identity politics began to intrude), so do the film’s filmic references harken back toward such films as Godard’s “Breathless” and other ‘60s classics, but through the prism of more recent works such as “Stranger Than Paradise,” “Slacker” and others.

That scheme of references may sound a bit dense on paper, but it helps explain why the film’s New Wave evocations come across not as static or precious idolatry (as purely aesthetic tributes tend to make them) but as part of an active, challenging dialectic that involves both politics and movies. In a sense, “Güeros” asks the viewer what the ‘60s were worth, in terms of its innovative popular art and its political radicalism—which of course were completely intertwined. Yet it doesn’t assume there are any clear-cut or easy answers. If the film comes at us with a heady appreciation for both the movies and revolutionary impulses of 1968, it does so with a witty circumspection that admits that their value has been continually amended and complicated by more recent developments.

And while Ruizapalacios has admitted other influences ranging from Ozu to Fellini to Monte Hellman, the New Wave does seem to be his pole star. You get that in the film’s focus on marginal, quasi-hipster characters; its self-reflexivity and cascade of cinematic and pop-culture nods; its winningly naturalistic performances, jerky, stop-start plotting and geographic peregrinations (the director has called it a road movie about Mexico City); and, most especially, in Damián Garcia’s exultant camerawork, which has a fluid, observant lyricism worthy of ace New Wave lensman Raoul Coutard.

In one sense, the film is a great lark, a dizzy road trip with some entertaining knuckleheads, both light-skinned and dark. Yet it also manages to be a movie with some serious things on its mind, for those who want to think about what it’s saying. More than perhaps any other country, Mexico has lobbed some real cinematic intelligence onto the world stage in recent years. “Güeros” continues that salutary tradition. A sly, insouciant masterpiece, it marks Alonso Ruizpalacios as a talent to watch.

Godfrey Cheshire, Roger Ebert.com.

Up all night in Mexico City: "Güeros," a gorgeous, ecstatic slacker odyssey, is one of the best movies of the year.

I had already decided that “Güeros,” a gorgeous slice of deadbeat Mexico City slacker poetry, was a work of genius even before the characters step out of the story (for the second time) to debate the movie with the director. These pretentious Mexican directors, one character complains (while sitting on a fancy terrace of a party he just crashed, drinking someone else’s booze), are painting an unfair picture of the country. Why do they want to make these arty movies in black-and-white featuring beggars and criminals? Then they go overseas to film festivals and convince French critics that Mexico is full of gangsters and hustlers and degenerates and phonies and corrupt politicians. But that’s all true, his friend observes. OK, the first guy admits, it is. But should they really get to make their movies on the taxpayers’ dime?

To be fair, “Güeros,” the whimsical, mysterious and subtly tragic debut feature from Mexican director Alonso Ruizpalacios, both is and is not the movie these guys are talking about. It is most certainly an art film, shot in black-and-white, that might well seem puzzling or pointless to many of Ruizpalacios’ fellow citizens (and to lots of other people besides). But it’s a story about dreamers, about deadbeats, about rebels without a cause, not about crime or poverty. “Güeros” is set in Mexico City during the 1999 student strike at UNAM, the gigantic national public university, and paints a highly specific romantic and satirical portrait of that time and place. Then again, it isn’t really about that at all – it’s a gorgeous sound-and-vision journey through a mystical or mythical space that has echoes of the 1960s Paris of Godard and Truffaut and the 1980s New York of Jim Jarmusch.

I don’t kid myself that this witty, delicate and often magical movie is likely to find a wide audience. But you don’t have to understand its points of reference in Mexican history and culture or speak Spanish or possess a dense mental thesaurus of art cinema in order to connect with it. If you have been young and felt disconnected from your surroundings, yet also felt the yearning for some ineffable meaning that lies behind it all but keeps slipping away, that’s plenty. “Güeros” is the foreign-language discovery of 2015 far, and pretty close to the best film I’ve seen all year.

The two guys who may be debating the merits of the movie they’re in are a dreamboat-handsome college dropout known as Sombra, which means “shadow” (Tenoch Huerta) and his best friend and roommate Santos (Leonardo Ortizgris). They are convincing and hilarious human characters and also archetypes of dissolution drawn from the history of pop culture. (They’d fit right in as the new Latino buddies in the household of Richard Linklater’s underappreciated “A Scanner Darkly,” for example.) Sombra and Santos have embarked on an odyssey, without quite intending to, in search of a dying Mexican rock hero who once made Bob Dylan cry. Their journey is both real and symbolic, and their story has elements of surrealism and postmodern self-referentiality, without ever quite abandoning everyday Mexican reality. (Which can get pretty weird.)

Ruizpalacios’ title is a derisive slang term applied to light-skinned Mexicans who betray European rather than mestizo or Indian ancestry, and the reference is so specific it has no English equivalent. “White boys” might be a rough cognate, but to call someone a güero is to imply softness and privilege, an upper-crust urban origin and a lack of real Mexican identity. Whether Santos and Sombra, and Sombra’s undeniably light-skinned little brother Tomás (Sebastián Aguirre), are in fact güeros is a point of unresolved controversy. As we eventually discover, “Los Güeros” is also the title of the only known album by the enigmatic Epigmenio Cruz, who may or may not have thrown his prospective ‘60s rock stardom away for a woman and may or may not have reduced Dylan to tears.

“Güeros” is full of those kinds of little echoes and resonances, but never in the service of some heavy-handed artistic agenda. If this is an ambitious movie it’s also a playful one devoted to capturing the wonder and mystery and loneliness of being young and adrift in a big city, and one that never loses sight of its central emotional drama. Back home in Veracruz, on Mexico’s Gulf Coast, Tomás has committed a minor act of juvenile delinquency – one that could have been disastrous and tragic, but wasn’t. That has convinced his mother to ship him off to Sombra (whose real name is Federico) in Mexico City, which could be construed as an all-time terrible parenting decision. Mom presumably doesn’t know that Sombra has fallen into a depressive philosophical funk that renders him a less than ideal caretaker. He has taken advantage of the UNAM strike to sit around and do nothing. He and Santos are “on strike from the strike,” as he puts it. They can only watch TV or keep their beer cold when they convince a young girl who lives downstairs to send up an extension cord in a basket. Why should they bother going out, Sombra muses, if they’re only going to end up coming back again?

For many Mexicans, especially those who came of age during that era, the ’99 UNAM strike looms in retrospect as an early battle against neoliberal economics, not to mention a signal defeat. (Believe it or not, the precipitating issue was the administration’s decision to start charging tuition – about $300 a year.) While the computers, the cars and the clothes are all roughly accurate, and Ruizpalacios’ portrayal of the hotheaded, self-absorbed and halfway appealing student radical movement is highly convincing, he also violates the period several times: We see upscale hipsters tapping on smartphones at the aforementioned party, and a few obvious eruptions of 21st-century architecture.

That kind of device could be irritating or affected in the wrong hands, but this is a movie where every movement of Damián García’s camera and every haunting snippet of music on the soundtrack – from vintage Mexican pop to Delta blues to Elvis singing “I Was the One” -- is part of a lovingly woven tapestry. It probably doesn’t help to compare one obscure film to another, but if “Güeros” bears many influences it reminds me most of Philippe Garrel’s 2005 “Regular Lovers,” an ironic and languorous ode to bohemian dissolution that both is and is not set against the Paris student uprising of 1968 (and is among the greatest and most overlooked works of recent French cinema). See them both, in whichever order you can.

What you thought about Güeros

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 (33%) | 5 (24%) | 8 (38%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 21 Film Score (0-5): 3.86 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

There were 68 user log ins to Güeros and 21 of you provided a response. This has delivered a

Film Score of 3.86.

Written responses are below.

“The student existence hasn't greatly changed since I was at art school then, Sombra even seems to be wearing my clothes. Once Tomas has jump started his brother an amusing, light-footed and disjointed journey ensues, as if the standard tropes of the coming of age movie had been cut up and glued together in random order. Shot in gorgeous New Wave black and white it owes as much to Kevin Smith and Richard Linklater as it does to Truffaut and Godard. It is full of fun; the singer whose music we never hear, the actors who complain to the director. I've no idea what the director's political stance is but I suspect broadly liberal judging by the detached and amused eye, far too much grandstanding, assumption of the moral high ground and petty and facile point scoring to fractionally advance the cause. Tremendously good fun”.

“I thought it was interesting but failed to get me engaged. I was never fully convinced about the quest (i.e. finding Cruiz) nor about their redemption in finding a way out of their ennui and finding things to look forward to. I was also not convinced about the Meta film aspects, i.e. the shots in the car with the Director or the meeting in the club with I assume Mexico's 'luvvies'. It felt strained. But good to see an aspect of urban Mexico and nice b&w photography”.

“Best moment. The group of kids finally catch up with cult singer beloved of the two brothers and their late father. Cue impassioned speech to the singer saying just how much he has always meant to them. Affecting or what? But the singer has fallen asleep cigarette in hand. Mirror image of what this film did to me”.

“Very stylish cinematography with a strong musical score. Found it much more watchable than I had expected - each shot was so beautifully crafted. Interesting and original”.

“Enjoyed its whimsical and mysterious nature; a sense of romance runs through this film about dreamers, bit of a road movie, delicate and often magical. Liked its ambition, as well as its playfulness. Hadn't recalled anything about that student strike at strike at UNAM, the huge national public university in Mexico City, but this captured a sense of the occasion well. Liked how Sombra (shadow!) and Santos are anti-heroes, rebels with no real cause, with a teenager tagging along. They're convincing as is Ana as Sombra's sort-of-girlfriend, with the three boys (?) for a while on the great Epigmenio quest. What an impression she makes on Tomás! So it's a film about things that fade away – musical heroes, loved girls or boys, improbable political wishes, and what they leave us with. The boys' desire to find a dying, unknown Mexican rock star to get his autograph on their cassette tape is a cause. We never hear the song, helps to develop the brothers bond by a force not quite seen. Reminded me of 1960s new wave, Godard and Truffaut use of specific camera angles beautiful film. Full of references to film as well. We never do understand if it's only Santos who is a guero implying a privileged background and no real Mexican identity - or maybe the whole group. A treat to watch”.

“Incomprehensible”.

“There were things about this film I really liked, the cinematography in particular, some of the actors, some of the themes covered. But it felt too disjointed and ultimately it didn't really hang together for me. Perhaps I'm just not clever enough to follow it! I wish I could have enjoyed the whole film more”.

“This was my second viewing after 5 years but I still do not accept the critical hype this film received”.

“Loved this film! Indie, quirky, touching, sad, uplifting, "if you're young and not a revolutionary it's a contradiction", great soundtrack, reminiscent of "Searching for Sugarman" (except that the musician dude falls asleep), French New Wave references, Kevin Smith eat your heart out. Did I say I loved it?”