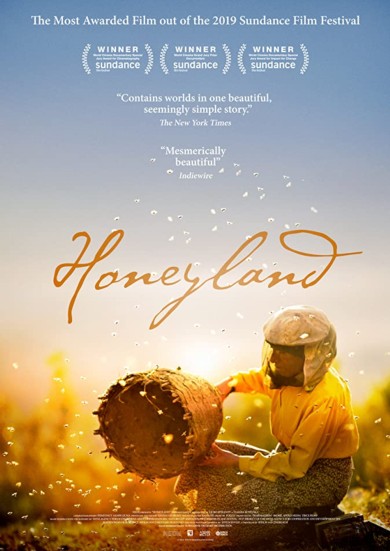

Honeyland

One of Europe’s last female bee-hunters deals with the threat of losing her bees and her livelihood in this mesmerising study of a different way of life. Multiple winner at Sundance 2019.

Film Notes

Honeyland review – beekeeper's life with a sting in the tale.

In this terrific documentary shot in North Macedonia, a woman tending wild hives is rattled by her new, disruptive neighbours.

This astonishing, immersive environmental documentary began life as a nature conservation video about one of Europe’s last wild-beekeepers. The scene is an abandoned village in North Macedonia where Hatidze, a woman in her mid-50s, harvests honey sustainably the traditional way from wild hives. “Half for them, half for me,” she chants, leaving enough for the bees.

Serendipitously for directors Tamara Kotevska and Ljubomir Stefanov (though not for Hatidze), the family from hell moves in next door mid-shoot, and this small-scale film takes on epic proportions, transforming into a parable about exploiting natural resources, or perhaps a microcosm of humans’ suicidal destruction of the environment.

Hatidze first appears on a dangerous cliff edge wearing no protective mask, a cloud of bees swarming as she removes honeycomb from a hive in rocks. She is an incredible woman, a natural optimist living in poverty – she and her frail elderly mother are the last inhabitants of their village, with no electricity or running water. Her life might not be the one she would have chosen, but Hatidze lives it with gusto, licking the plate clean. Animals and small children trust her instinctively.

When an itinerant cow herder pitches up with his wife and seven rowdy children, Hatidze seems glad of the company. She even teaches Hussein beekeeping. Just don’t take too much honey, she cautions. Her warnings go unheeded with terrible consequences. But Hussein isn’t a villain; he’s a man with debts and a family to feed. And what a family – a five-year-old hammering at rusty nails with a chunk of rock, the toddler tottering into frame as a bull rampages through the cow herd.

Honeyland really is a miraculous feat, shot over three years as if by invisible camera – not a single furtive glance is directed towards the film-makers. As for Hatidze, you could watch her for hours. In a heart-tugging scene with one of Hussein’s sons, a favourite of hers, he asks why she didn’t leave the village. “If I had a son like you, it would be different,” she answers. They both look off wistfully, dreaming of another life, a world of harmony.

Cath Clarke, The Guardian, 11th September 2019.

Film Review: ‘Honeyland’

Macedonian docmakers Ljubomir Stefanov and Tamara Kotevska make a visually poetic debut with this stark, wistful portrait of a lone rural beekeeper.

The opening frames of “Honeyland” are so rustically sumptuous that you wonder, for a second, if they’ve somehow been art-directed. Elegantly dressed in a vivid ochre blouse and emerald headscarf, captured in long shot as she nimbly wends her way through a craggy but spectacular Balkan landscape, careworn middle-aged beekeeper Hatidze Muratova heads to check on her remote, hidden colony of bees — delicately extracting a dripping wedge of honeycomb the exact saturated shade as her outfit. With man and nature so exquisitely coordinated, it’s as if Hatidze herself has grown from the same rocky land, and in a sense, she has. Scraping by with her ailing mother Nazife on a tiny, electricity-free smallholding in an otherwise unpopulated Macedonian mountain settlement, Hatidze has known no other life, and has certainly seen more bees than people in her time.

In Ljubomir Stefanov and Tamara Kotevska’s painstaking observational documentary, everything from the honey upwards is organic. Shot over three years, with no voiceover or interviews to lead the narrative, “Honeyland” begins as a calm, captured-in-amber character study, before stumbling upon another, more conflict-driven story altogether — as younger interlopers on the land threaten not just Hatidze’s solitude but her very livelihood with their newer, less nature-conscious farming methods. As a plain environmental allegory blossoms without contrivance from the cracks, Stefanov and Kotevska’s ravishingly shot debut accrues a subtle power that will be felt by patient festival audiences, though only refined boutique distributors need apply.

Hatidze remains the film’s compelling center even as stakes and circumstances shift around her. A resilient grafter with a gentle sense of humor that survives her calloused demeanor, she’s the kind of subject who’s fascinating to watch even when doing nothing at all — which admittedly isn’t often, given her grinding routine of working the land, harvesting the honey, trekking to distant Skopje to sell her sweet, sticky wares, and returning to care for the half-blind, 85-year-old Nazife. (“I’m not dying, I’m just making your life misery,” the old woman taunts.) Shooting often by scant candlelight, the filmmakers capture the claustrophobic intimacy of a terse mother-daughter relationship, in which tough love is expressed through provision, not terms of endearment.

Contentedly independent the never-married Hatidze may be, but that’s not to say she’s averse to other people’s company. So when itinerant Turkish couple Hussein and Ljutvie noisily set up their caravan on an adjacent lot, with seven young children in tow, Hatidze initially welcomes them with neighborly cheeriness: The rowdy kids, in particular, take to her, while she’s happy to offer advice when Hussein takes an interest in her beekeeping enterprise. But where her honey business is founded on a golden “take half and leave half” rule — a quota that retains enough honey for the bees themselves to live on — Hussein has no time for such restraint. Before long, his greedier, more profit-minded approach clashes bitterly with Hatidze’s; though he’s hardly an industry, his ineffective business model stands in for a world of capitalist commerce, threatening the delicate ecosystem into which Hatidze has sensitively integrated herself.

There’s humor in this battle of wills, some of it via Nazife’s surprisingly caustic interjections: “May God burn their livers,” she moans as the family’s shrill squabbling is heard from across the field. Stefanov and Kotevska aren’t quite as unsympathetic to the intruders’ woes, spending a generous amount of time observing their desperate, fractious familial bond: Misguided and peace-disturbing as his methods are, Hussein, too, is just trying to get by. The line between victim and villain is a fine one here — Hatidze herself regards it with shrugging frustration — and that ambiguity gives “Honeyland” an unexpectedly rich seam of moral tension.

Under the gilded gaze of cinematographers Fejmi Daut and Samir Ljuma, however, this magnificent landscape remains stoically undisturbed by human drama. The camera doesn’t unduly prettify Hatidze’s surroundings, but it’s hard not to occasionally gasp at its veritable khaki rainbow of grass, sand and stone: tintedly different from season to season, but with ancient, stony textures fixed in place. The implacability of this deserted, wind-kissed environment makes Hatidze and Nazife’s looming mortality all the more poignant: It’s hard not to wonder if someone else will pick over these winding mountainside paths once their time comes. Perhaps, just perhaps, the bees will eventually get to keep both halves of the honey.

Guy Lodge, Variety, 1st Feb 2019.

What you thought about Honeyland

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 (50%) | 11 (39%) | 3 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 28 Film Score (0-5): 4.39 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

There were 145 devices watching Honeyland online - which means even more people watching it because we're hearing about some people getting together for a Tuesday night screening, or couples and families watching together. We're delighted you're still enjoying some sociability that is at the heart of the society.

Overall a lot of people liked this documentary very much. The responses are all below, and we're pleased the story and characters at the heart of the film evoked such reactions:

"What a fascinating insight into a completely different lifestyle & environment. I thought the filming style was empathetic and managed to feel spontaneous rather than over directed. Amazing landscape..loved the plane vapour trail hinting at another place.."

"Such a beautifully made film that honoured the dedicated work and tough life of this simple, yet optimistic, woman. Her natural rapport with the bees was so tender and her pleasure in having children around her to break her isolation was very touching, as was her dedication to her mother. The environmental destruction off the ignorant noisy neighbours was a stark contrast. A very thought provoking film. Thanks for showing it."

"Thanks for showing this visually captivating film, but one also full of extraordinary tensions. A striking look at an endangered tradition with a coherence that good quality verité can bring. A powerful movie yet frustrating as it felt like a constructed narrative. I wondered what Hatidze thought of the film makers, and who had arranged the shooting, for example, of the sequence where she removes the honeycomb from the rocks and scooping out bees. Did the filmakers' presence affect what she did and maybe how she thought? But a strong sense of how she is at one with the bees threads through the film. Her methods are personal and humane as she doesn't limit the bees store of honey to make too much money but looks after the hives with great care. I wondered why the village she lived in with her mother had been depopulated – film makers don't offer a view of that – and her life seems autonomous but very lonely. Sure she goes into the city to sell honey (liked her green haired companion!), but we know that if she'd had a son then life may have been different. Why did Hatidze's father turn down marriage offers for her; I would have liked to know. Conflict between her and neighbours is slowly unfurled; quick money making versus conserving bees symbolises the difference in the lives of Hussein and Hatidze. Mass produced honey that threatens this resilient woman's entire existence. Hell is other people! Thought camerawork reflected rocky terrain, its ruins and Hatidze. The shadows and candlelight inside the hut, the occasional 'plane streaming the sky. A moving moment with the stricken look of compassion on a boy's face after she answers his not-so-simple question: Why don't you leave this place? Hmm ..."

"This is a film of great, quiet resonance. An eloquent plea for patience and empathy which, though beautifully shot it, is ultimately quite depressing. The winner is Hussein's loathsome boss, rinsing him for everything he can get, Hussein, a weak man in a hard place, survives but gains nothing, Hatidze, the only one at peace and in harmony with her environment, loses everything. Has Film Soc ever shown 'Koyaanisqatsi'? A film I was reminded of both in thematic and cinematographic terms, a similarly beautiful prayer for sanity and economy in regard to the environment. I am delighted to note Hatidze, a rare combination of nobility and fun, reaped some benefits from the film's success but Wiki does not note whether she was able to re-establish her hives. I do hope so."

"Mesmerised by some beautiful shots of the contrast of light and darkness as in Flemish Renaissance paintings. I could not believe it was a documentary - it was a microcosm of toxic society condensed in the simple relationship between the beehive lady and the family. Without handling with care, things go horribly wrong and the risk being stung. The buzzing noise is effectively used as warning, anxiety and even a threat but it also sounded comforting when the bee-lady handled them."

"Stunning. A very beautiful, moving film. Fantastic."

"Very interesting film about an area and topic I knew nothing about.

Good to see an aspect of the Balkans without ethnic tension and violence."