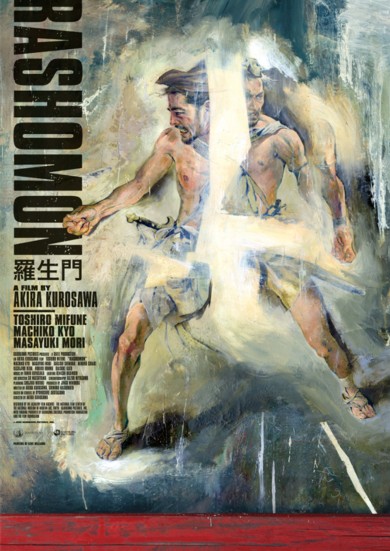

Rashomon

The story of the rape of a bride and the murder of her Samurai husband told from various points of view in this meditation on human nature. One of the most influential films of all time.

Film Notes

THE SCREEN IN REVIEW; Intriguing Japanese Picture, 'Rasho-Mon,' First Feature at Rebuilt Little Carnegie

A doubly rewarding experience for those who seek out unusual films in attractive and comfortable surroundings was made available yesterday upon the reopening of the rebuilt Little Carnegie with the Japanese film, "Rasho-Mon." For here the attraction and the theatre are appropriately and interestingly matched in a striking association of cinematic and architectural artistry, stimulating to the intelligence and the taste of the patron in both realms.

“Rasho-Mon," which created much excitement when it suddenly appeared upon the scene of the Venice Film Festival last autumn and carried off the grand prize, is, indeed, an artistic achievement of such distinct and exotic character that it is difficult to estimate it alongside conventional story films. On the surface, it isn't a picture of the sort that we're accustomed to at all, being simply a careful observation of a dramatic incident from four points of view, with an eye to discovering some meaning—some rationalization—in the seeming heartlessness of man.

At the start, three Japanese wanderers are sheltering themselves from the rain in the ruined gatehouse of a city. The time is many centuries ago. The country is desolate, the people disillusioned, and the three men are contemplating a brutal act that has occurred outside the city and is preying upon their minds. It seems that a notorious bandit has waylaid a merchant and his wife. (The story is visualized in flashback, as later told by the bandit to a judge.) After tying up the merchant, the bandit rapes the wife and then—according to his story—kills the merchant in a fair duel with swords.

However, as the wife tells the story, she is so crushed by her husband's contempt after the shameful violence and after the bandit has fled that she begs her husband to kill her. When he refuses, she faints. Upon recovery, she discovers a dagger which she was holding in her hands is in his chest. According to the dead husband's story, as told through a medium, his life is taken by his own hand when the bandit and his faithless wife flee. And, finally, an humble wood-gatherer—one of the three men reflecting on the crime—reports that he witnessed the murder and that the bandit killed the husband at the wife's behest.

At the end, the three men are no nearer an understanding than they are at the start, but some hope for man's soul is discovered in the willingness of the wood-gatherer to adopt a foundling child, despite some previous evidence that he acted selfishly in reporting the case. As we say, the dramatic incident is singular, devoid of conventional plot, and the action may appear repetitious because of the concentration of the yarn. And yet there emerges from this picture—from this scrap of a fable from the past—a curiously agitating tension and a haunting sense of the wild impulses that move men. Much of the power of the picture—and it unquestionably has hypnotic power—derives from the brilliance with which the camera of Director Akira Kurosawa has been used. The photography is excellent and the flow of images is expressive beyond words. Likewise the use of music and of incidental sounds is superb, and the acting of all the performers is aptly provocative.

Machiko Kyo is lovely and vital as the questionable wife, conveying in her distractions a depth of mystery, and Toshiro Mifune plays the bandit with terrifying wildness and hot brutality. Masayuki Mori is icy as the husband and the remaining members of the cast handle their roles with the competence of people who know their jobs. Whether this picture has pertinence to the present day—whether its dismal cynicism and its ultimate grasp at hope reflect a current disposition of people in Japan—is something we cannot tell you. But, without reservation, we can say that it is an artful and fascinating presentation of a slice of life on the screen. The Japanese dialogue is translated with English subtitles.

Bosley Crowther, The New York Times, December 27th 1951.

Spy magazine in the 1990s had a witty essay on how, in American journalism, it only took a couple of slightly conflicting accounts of the same event for someone to trot out the word "Rashômon". Here is an opportunity to revisit Akira Kurosawa's 1950 film, and to appreciate how the cliché does not do justice to a uniquely disturbing drama.

Rashômon is about a court proceeding, recalled in flashback, relating to a mysterious crime. A bandit, Tajômaru (Toshirô Mifune) is on trial for murdering a samurai (Mayasuki Mori) and raping his wife (Machiko Kyô) in the remote forest. Each of these three figures addresses the court, the dead man via a medium – an amazingly, electrifyingly strange conceit, carried off with absolute conviction. A fourth witness (Takashi Shimura) offers his own version, again different. But it is not just a matter of the witnesses being slippery: crucially, the bandit, the samurai and the samurai's wife each claim to have committed the murderous act themselves, the samurai by suicide. Truth, history, memory and the past … are these just fictions?

One character is told that lying is natural for all of us, and it is in the discrepancies that the essence of our humanity resides. Kurosawa invests the unknowability of the event with horror, suggesting that the three of them somehow chanced upon, or created, a black hole in human thought and communication, whose confusion and violence can never be clearly explained or remembered, as in the Marabar caves in A Passage to India with their endless echoing "Bo-oum". Unmissable.

Peter Bradshaw, the Guardian, 17th June 2010.

Shortly before filming was to begin on "Rashomon," Akira Kurosawa's three assistant directors came to see him. They were unhappy. They didn't understand the story. "If you read it diligently," he told them, "you should be able to understand it, because it was written with the intention of being comprehensible." They would not leave: "We believe we have read it carefully, and we still don't understand it at all."

Recalling this day in Something Like an Autobiography, Kurosawa explains the movie to them. The explanation is reprinted in the booklet that comes with the new Criterion DVD of "Rashomon." Two of the assistants are satisfied with his explanation, but the third leaves looking puzzled. What he doesn't understand is that while there is an explanation of the film's four eyewitness accounts of a murder, there is not a solution.

Kurosawa is correct that the screenplay is comprehensible as exactly what it is: Four testimonies that do not match. It is human nature to listen to witnesses and decide who is telling the truth, but the first words of the screenplay, spoken by the woodcutter, are "I just don't understand." His problem is that he has heard the same events described by all three participants in three different ways--and all three claim to be the killer.

"Rashomon" (1950) struck the world of film like a thunderbolt. Directed by Kurosawa in the early years of his career, before he was hailed as a grandmaster, it was made reluctantly by a minor Japanese studio, and the studio head so disliked it that he removed his name from the credits. Then it won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, effectively opening the world of Japanese cinema to the West. It won the Academy Award as best foreign film. It set box office records for a subtitled film. Its very title has entered the English language, because, like "Catch-22," it expresses something for which there is no better substitute.

In a sense, "Rashomon" is a victim of its success, as Stuart Galbraith IV writes in The Emperor and the Wolf, his comprehensive new study of the lives and films of Kurosawa and his favorite actor, Toshiro Mifune. When it was released, he observes, nobody had ever seen anything like it. It was the first use of flashbacks that disagreed about the action they were flashing back to. It supplied first-person eyewitness accounts that differed radically--one of them coming from beyond the grave. It ended with three self-confessed killers and no solution.

Since 1950 the story device of "Rashomon" has been borrowed repeatedly; Galbraith cites "Courage Under Fire," and certainly "The Usual Suspects" was also influenced, in the way it shows us flashbacks that do not agree with any objective reality. Because we see the events in flashbacks, we assume they reflect truth. But all they reflect is a point of view, sometimes lied about. Smart films know this, less ambitious films do not. Many films that use a flashback only to fill in information are lazy.

The genius of "Rashomon" is that all of the flashbacks are both true and false. True, in that they present an accurate portrait of what each witness thinks happened. False, because as Kurosawa observes in his autobiography, "Human beings are unable to be honest with themselves about themselves. They cannot talk about themselves without embellishing."

The wonder of "Rashomon" is that while the shadow play of truth and memory is going on, we are absorbed by what we trust is an unfolding story. The film's engine is our faith that we'll get to the bottom of things--even though the woodcutter tells us at the outset he doesn't understand, and if an eyewitness who has heard the testimony of the other three participants doesn't understand, why should we expect to?

The film opens in torrential rain, and five shots move from long shot to closeup to reveal two men sitting in the shelter of Kyoto's Rashomon Gate. The rain will be a useful device, unmistakably setting apart the present from the past. The two men are a priest and a woodcutter, and when a commoner runs in out of the rain and engages them in conversation, he learns that a samurai has been murdered and his wife raped and a local bandit is suspected. In the course of telling the commoner what they know, the woodcutter and the priest will introduce flashbacks in which the bandit, the wife and the woodcutter say what they saw, or think they saw--and then a medium turns up to channel the ghost of the dead samurai. Although the stories are in radical disagreement, it is unlike any of the original participants are lying for their own advantage, since each claims to be the murderer.

Kurosawa's screenplay is only the ground which the film travels, however. The real gift of "Rashomon" is in its emotions and visuals. The cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa evokes the heat, light and shade of a semi-tropical forest. (Slugs dropped from trees onto the cast and crew, Kurosawa recalled, and they slathered themselves with salt to repel them.)

The woodcutter's opening journey into the woods is famous as a silent sequence which suggests he is traveling into another realm of reality. Miyagawa shoots directly into the sun (then a taboo) and there are shots where the sharply-contrasted shadows of overhead leaves cast a web upon the characters, making them half-disappear into the ground beneath.

In one long sustained struggle between the bandit (Mifune) and the samurai (Masayuki Mori), their exhaustion, fear and shortness of breath becomes palpable. In a sequence where the woman (Machiko Kyo) taunts both men, there is a silence in which thoughts form that will decide life or death. Perhaps the emotions evolved in that forest clearing are so strong and fearful that they cannot be translated into rational explanation.

The first time I saw the film, I knew hardly a thing about Japanese cinema, and what struck me was the elevated emotional level of the actors. Do all Japanese shout and posture so? Having now seen a great many Japanese films, I know that in most of them the Japanese talk in more or less the same way we do (Ozu's films are a model of conversational realism). But Kurosawa was not looking for realism. From his autobiography, we learn he was struck by the honesty of emotion in silent films, where dialog could not carry the weight and actors used their faces, eyes and gestures to express emotion. That heightened acting style, also to be seen in Kurosawa's "Seven Samurai" and several other period pictures, plays well here because many of the sequences are, essentially, silent.

Film cameras are admirably literal, and faithfully record everything they are pointed at. Because they are usually pointed at real things, we usually think we can believe what we see. The message of "Rashomon" is that we should suspect even what we think we have seen. This insight is central to Kurosawa's philosophy. The old clerk's family and friends think they've witnessed his decline and fall in "Ikiru" (1952), but we have seen a process of self-discovery and redemption. The seven samurai are heroes when they save the village, but thugs when they demand payment after the threat has passed. The old king in "Ran" (1985) places his trust in the literal meaning of words, and talks himself out of his kingdom and life itself.

Kurosawa's last film, "Madadayo" made in 1993 when he was 83, was about an old master teacher who is visited once a year by his students. At the end of the annual party, he lifts a beer and shouts out the ritual cry "Not yet!" Death is near, but not yet--so life goes on. The film's hero is in some sense Kurosawa. He is a reliable witness that he is not yet dead, but when he dies no one will know less about it than he will.

Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun Times, May 26, 2002

What you thought about Rashomon

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 (47%) | 7 (37%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 19 Film Score (0-5): 4.21 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

67 users logged in to watch Rashomon (along with many more who also watched but we can only report on log ins). Very good responses from people who have seen the film previously and were experiencing it for the first time. Comments are below.

"Great story telling although I am not sure evidence from a medium would be acceptable today."

"Haven't watched Rashomon for many years, so was delighted to see it again. Can imagine the impact it had 70 years ago, especially from Japan post WW2, a country no longer having the cultural identity from military excellence and samurai principles. A powerful portrait of people (humanity?) at their weakest, yet the hope in the last scene lifts us. Setting up the over dramatized performances take us back to silent movies. The contrasts of dark and light, good and evil, truth and lies echoed constantly. Thought that Mifune, the bandit, and Kyo, the wife, were captivating in the intensity expressed in facial expressions, exaggerated laughs (usually in order to mock), and gestures (instead of words). The commoner acts in similar fashion, with this trait obvious in the last sequence. Conversely, the laconic woodcutter is restrained, showing a real dignity. Kurosawa sets the puzzle with 3 men trying to reach the truth, using their memories of the testimonies of the bandit, the wife and the samurai; but we never learn the truth, neither about the actual event nor the court's decision. Uncertain events disrupt the idea that film, as a medium, is truth itself since image coincides with fact. Here the camera seems to lie constantly. Still couldn't decide which version to accept. Thanks so much for showing this beautiful and powerful movie."

"A stunning start to the New Year. A film I'd not seen before but you feel you must have done as so many of the elements are so familiar, particularly from Westerns. Was Kurosawa influenced by Ford and Huston or the other way around? Do we see the original of 'The Searchers' doorway at the end? Certainly Sergio Leone must have studied this carefully. 1950 is very close to the end of the war. In the apparently novel conceit of the alternative narratives is there an element of querying Japan's recent past history and the way in which it was related to the public? Still feels vital and startlingly modern. Excellent.

Apologies for lack of reviews recently. I've watched the films but have been furiously busy and writing reviews fell off the to do list. Am sad 'Caravaggio' was not better liked. Enjoyed seeing it again. My favourite renaissance artist when I was about twelve."

"Terrific film. Very good cinematography and well constructed.

I am not sure about the credibility of the 'Good wins out over evil.' - it felt rather tacked on rather than a development of the narratives(s) that had gone on before.

It makes me want to seek out other Kurosawa. There must be more than Seven Samurai."

"Captivating and comprehensible for once. High drama certainly with very effective use of lighting. Couldn't quite get the point of the appearance of a baby right at the end but well worth watching."