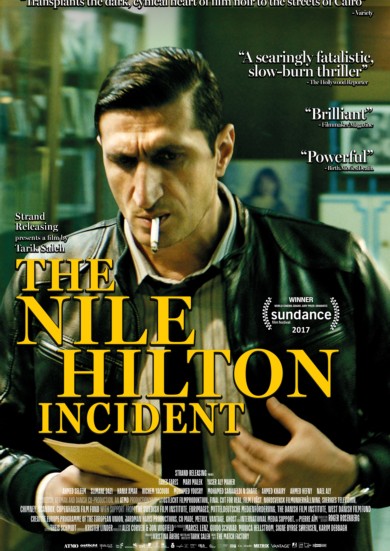

The Nile Hilton Incident

Well-crafted political thriller set against the backdrop of the Egyptian Revolution, in which a police officer investigates the murder of a woman amongst the elite classes.

Film Notes

Film Review: ‘The Nile Hilton Incident’.

An Egyptian cop tries to unravel a murder mystery in the days before the country’s 2011 revolution in Tarik Saleh’s potently bleak neo-noir.

Proof that classical genres are always ready to be retrofitted for the modern age, “The Nile Hilton Incident” transplants the dark, cynical heart of film noir to the streets of Cairo in the days leading up to the 2011 revolution that would eventually oust President Hosni Mubarak. Swedish writer-director Tarik Saleh’s crime drama about a cop investigating the murder of a beautiful singer is a paranoid portrait of individual and systemic corruption that leaves none of its characters unscarred. Blending procedural thrills with politicized commentary, this gripping import (based, in part, on a real-life 2008 case) should attract sizable domestic interest following its premiere at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.

Millions of Egyptians began protesting Mubarak’s reign beginning on Jan. 25, 2011 – a date that serves as the climactic setting of “The Nile Hilton Incident.” Saleh’s film commences shortly before that momentous turn of events, with a young Sudanese girl named Salwa (Mari Malek) who, while working as a cleaning lady at the titular hotel, overhears an argument in a room, out of which two men, in relatively brief succession, leave, the second one after having killed a woman. Salwa escapes this assassin, and tidying up the mess is left to Noredin (Fares Fares), a cop who has few qualms about pilfering cash from the scene of the crime, but who nonetheless is compelled to figure out who’s behind this murder, even though his superiors, including his uncle, Kamal (Yasser Ali Maher), are eager to sweep it under the rug.

Noredin’s inquiry immediately points him toward Shafiq (Ahmed Seleem), a real-estate developer and parliament member. Shafiq denies responsibility for the death of the girl, a local singer and prostitute named Lalena, who it turns out worked with a sleazy pimp named Nagy (Hichem Yacoubi) to take compromising photos of her clients (including Shafiq) that could then be used as blackmail. The film’s intro sequences makes clear that Shafiq had another mystery man (Slimane Daze) actually do away with Lalena. And the fact that these would-be culprits are both in league with – and shielded by – the police and governmental bigwigs is obvious to everyone, including Noredin, who finds himself at every turn stymied by people, and institutions, more concerned with self-interest than the truth.

After chasing numerous avenues that culminate in dead ends (as well as ominous warnings about his own professional and personal safety), Noredin is informed by Shafiq, “There’s no justice here.” That reality is as inescapable as the smog is thick in Cairo, a city the movie presents as a fugue-like dystopian wasteland littered with the bodies of innocents and the broken shards of the laws intended to protect them. Director Saleh’s frequent cutaways to his metro skyline evoke a sense of “Chinatown”-by-way-of-“Blade Runner” bleakness, while his infrequent snippets of TV news footage create anticipation for a forthcoming revolutionary conflagration set to engulf everyone and everything in its path.

Stuck in the center of this cesspool, Noredin proves incapable of affecting anything resembling real change, and Fares’ performance – all world-weary resignation and desperate righteousness – captures a poignant sense of helplessness. That’s especially true when he decides to become involved with Gina (Hania Amar), a friend of Lalena’s who’s also engaged in the crooner-cum-working-girl trade. Still grieving over his dead wife, Noredin knows that his behavior will invariably compromise him (and his investigation). Still, he proceeds accordingly, desperate for a sliver of genuine human connection, and buoyed by his knowledge that any indiscretion can be washed away with a bribe.

By the time it arrives at its showdown amid Cairo’s burgeoning uprising, “The Nile Hilton Incident” has indulged in so many grim twists that it’s hard not to read it, and its downbeat ending, as a stinging commentary on the venality of the Mubarak era, as well as the futility of the forthcoming revolution to hold the nation’s actual villains accountable. Like the finest noir, what springs forth from Saleh’s film is the dreary belief that the bad sleep well while the rest are left to suffer in the streets.

Nick Schager, Variety, Jan 21, 2017.

'The Nile Hilton Incident': Sundance Review.

A true-life celebrity murder case that ran for years in the Egyptian media is the springboard for Swedish director Taleh’s latest feature, a nuanced police procedural set against the background of the Tahrir Square protests of January 2011 which, like Andrej Zvyagintsev’s Leviathan, charts one man’s deluded attempt to do the right thing in a world where money and power are the only moral arbiters.

This draws on vintage European and Stateside models in its take on systemic police corruption and its moody noirish feel.

A moody, intense Fares Fares (launched by Jalla! Jalla! and now an increasingly familiar Hollywood character actor) commands attention as a weary urban cop mired in a world of backhanders and political influence, who decides, cussedly, and masochistically, to investigate a powerful parliamentarian and businessman in connection with a sleazy murder charge.

There’s none of the melodrama that tends to infect even edgy homegrown ‘auteur’ films from Egypt in this Sundance World Cinema Dramatic Competition premiere, and none of the prudishness either: this even becomes a visual joke in one key scene when the camera pans away from a couple about to get down and dirty, only to catch them in the act in a wardrobe mirror. Set in Cairo but shot in Morocco and Germany, The Nile Hilton Incident draws more on vintage European and Stateside models in its take on systemic police corruption and its moody noirish feel: The French Connection, Heat and Jean-Pierre Melville are all there in the mix, while the Tahrir Square protest backdrop recalls the way the Rodney King riots were used in another rotten police saga, Dark Blue.

Though few outside the Arab world will have registered the news story that underpins the plot, the film’s uniquely Egyptian twist on the contemporary hard-boiled dirty cop genre will lend it some heft in receptive arthouse markets. It doesn’t hurt that this is a good-looking package, with Krister Linder’s pulsating electronic soundtrack and veteran French DoP Pierre Aim’s depiction of a user-unfriendly urban jungle where murky haze or harsh dazzle seem to be the only available lighting settings.

The investigation that comes to obsess Fares’ character, police major Noredin, is based loosely on the case of a glamorous Lebanese pop star, Suzanne Tamim, who was found dead in her Dubai apartment in July 2008. In May 2009, a prominent Egyptian Shura Council lawmaker and businessman was convicted of her murder, along with the hitman he had paid to carry out the killing. When both men were found guilty and sentenced to death, justice seemed to have been served on a rich and powerful member of the Cairo establishment – but it didn’t last long, with Egypt’s Supreme Court quashing the earlier ruling on a technicality in March 2010, and commuting the politician’s sentence to 15 years.

Saleh, a former graffiti artist and documentary maker whose 2010 crime thriller Tommy steered him into noir territory, plays fast and loose with the facts, characters and dates, condensing the story arc down to ten days and shifting the action forward to January 2011, when the revolution that would eventually topple president Hosni Mubarak kicked off. The murder takes place not in Dubai but in the luxury Cairo hotel that gives the film its name (now the Ritz-Carlton).

World-weariness and self-disgust mix with a certain dangling-cigarette cool in the character of Noredin, a pill-popping, dope-smoking, leather-jacketed cop inured to the bribes, deals and favours that go down in a precinct presided over by his police chief uncle, Kammal. Noredin takes the same backhanders and protection money as his colleagues, but it’s clear he didn’t sign up for this. When Kammal assigns him to the case of Lalena, a celebrity singer who was found murdered in a room at the Nile Hilton, he becomes doggedly absorbed in the investigation, persisting even when it leads to the door of Hatem Shafiq, a construction magnate and member of parliament who beams down from billboards across the city with the promise that he is “building the new Cairo”.

Genre touches – forays into a Cairo underworld of sleazy drinking dens, opium parlours and sexy cabaret joints, some touches of bitter humour, a steamy liaison with a femme fatale torch singer – are mostly well blended in with the film’s social commentary. One important strand of this focuses, through the character of a Sudanese chambermaid who witnessed the crime, on the dire plight of sub-Saharan immigrants in a country where life is already tough enough.

There’s a small loss of impetus in the closing scenes, when the street protests that exploded on 25 January provide rather too neat a conclusion to a necessarily messy story. But at least it allows a film poised between righteous anger and resigned cynicism to remind us how this particular revolution ended up. When a protestor stops others beating up the gun-toting Noredin because “we are not like them”, the irony is deafening.

LEE MARSHALL, Screen Daily, 20 JANUARY 2017

What you thought about The Nile Hilton Incident

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 (26%) | 16 (59%) | 3 (11%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 27 Film Score (0-5): 4.07 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

The Nile Hilton Incident.

59 users logged in to watch The Nile Hilton Incident. There were 27 responses delivering a film score of 4.07.

All written responses are below.

“Moody, intense without melodrama. Liked the weary urban cop deep in backhanders and political interference, investigating murder with some machismo. Kept on thinking of European and US movies in the systemic police corruption with a noirish taint: The French Connection, Heat a recall of the Rodney King riots in the corrupt police saga, Dark Blue. My sympathies kept shifting; what do I think of this pill-popping, dope-smoking, leather-jacketed cop? Is he better than any of the others? Not at all; the innocence of the maid is crushed in the maelstrom of bungs, torture and street protest. Gritty cinematography, vibrant, immersive, speckled indigo and brown. Dreariness to the fore it was fascinating to watch, as well as showing melancholy alongside the brutal and intrigue. The ironic ending with "we are not like them", added to the anger and cynicism. A cracking good watch.”

“'The Nile Hilton Incident' is undoubtedly noir; it's all there; the cop, the corruption, the endless smoking, the mean streets, the femme fatale, the bad guy who thinks he's above the law, the innocent in constant danger ...and the body and the blood soaking into the carpet. A plot every bit as complex as Chandler, pacy as Hammett, mood as dark as anything Thompson or Goodis ever wrote. But it's grubbier and more hopeless than these, the only Hollywood movie that comes close to the cynicism and endless corruption, especially in the bleak finale with Kammal, is 'Chinatown' and that's saying something. In look and feel it's more the weary colour of the seventies 'The Long Goodbye' than the crisp black and white of the forties but it feels more French than American, Noredin could have stepped from a Jacques Tardi bande dessinée. In the end the tireless venality of the police, with the collective moral rigour of a sewer rat (Noredin's hat is only a shade or two less black than the rest of the crew), is exhausting and the river of people who wash him away at the end one assumes may be seen to be wiping the slate clean. I'm not holding my breath. Superb. What quality retro noir have we not seen GFS?”

“Very enjoyable. Taught and convincing”.

“A really thrilling film. Sad ending where the hero (who has had his cover as a cop cynically broken by his boss) is saved from being beaten to death by the revolutionaries as a result of an idealistic intervention to stop the beating because: “we are not like them".

“The film provided a good and depressing primer on why the revolution did not prosper”.

“A study of corruption - and degrees of corruption. From the cleaning girl trying to get some easy money through blackmail to the protagonist Noredin (is he a good cop gone bad, or a bad cop who is essentially good?) through to his uncle, Mr. Kammal who with his well-fed face and dyed hair has no conscience left at all. It's all cleverly woven into the backdrop of civil and political unrest and also the plight of Sudanese refugees”.