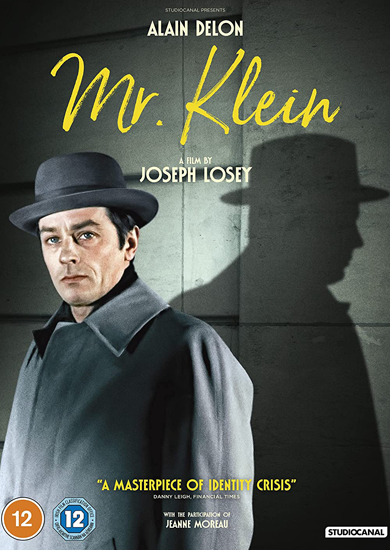

Mr Klein

An art dealer called Robert Klein (Alain Delon), doing well in Nazi-occupied Paris, is linked to a mysterious Jewish doppelgänger. Jeanne Moreau co-stars. Strong direction and stunning cinematography.

Film Notes

Review: Joseph Losey’s 1976 classic ‘Mr. Klein’ starring Alain Delon still enthralls.

The shock of seeing Joseph Losey’s newly restored, long unavailable “Mr. Klein” is not so much surprise at how compelling it is but astonishment at how it seems more relevant today than it did at its original 1976 release.

Moody, elegantly disturbing and impeccably made by a master director, this story of blurred identities and casual immorality in German-occupied Paris benefits from what might be the best performance of star Alain Delon’s long career as well as potent cameos by Jeanne Moreau, Michel Lonsdale and Juliet Berto.

The movie’s gifts were acknowledged at the time, with Césars for film, director and production design (by the legendary Alexandre Trauner) as well as nominations in four other categories.

But there was criticism as well for Losey as an expatriate American (in Europe fleeing the Hollywood blacklist) making a French language film set against one of that country’s darkest moments, the Vel d’Hiv roundup.

That 1942 event saw French police, not German soldiers, carrying out a mass arrest of some 13,000 foreign Jews living in Paris, something that no one expected and few survived.

Losey, working largely with “Battle of Algiers” screenwriter Franco Solinas (though Costa-Gavras and Fernando Morandi also worked on the script), said that his experience with the blacklist years influenced the wartime atmosphere of desperation and despair he created.

The aim of the prevailing cultural mood in both periods, he said in an interview with critic Michel Ciment, “is to make everybody on the street so frightened that they won’t even remotely engage in any kind of activity.”

What this means in practice is that the story arc of “Mr. Klein” is anything but a world of simplistic finger pointing.

Instead, using the elliptical style of earlier movies like “The Servant” and “Accident,” Losey created a Kafkaesque world where everyone is vulnerable and no one is on safe ground, a world where nothing is certain, not even your own identity. Especially your own identity.

In the Paris of 1942, Robert Klein is introduced as the master of all he surveys, an art dealer taking advantage of Jews desperate for cash to leave the country by buying their collections at bargain prices.

At his ease in his opulent apartment, wearing a florid dressing gown with a complaisant mistress (Berto) waiting in his bedroom, the opportunistic Klein provides Delon, one of France’s biggest stars who often graced commercial thrillers, a chance to focus on a different kind of role.

No one could do pitiless men in a pitiless world better than Delon, an actor who held the screen without apparent effort. But in “Mr. Klein,” he is equally good at providing an acute psychological portrait of what happens when the façade begins to crack, when ground that seemed firm underfoot proves to be less so.

It all begins when a Jewish newspaper addressed to Robert Klein by name lands on his doorstep. In a world where no mistake can be assumed to be innocent, a world where “Jews Forbidden” signs are posted on café doors, this minor incident is a fly in Klein’s ointment, and he becomes increasingly obsessed with figuring out why it happened.

It is one of the conceits of “Mr. Klein” that the more the man investigates, visiting first the newspaper’s office and then the unnerving Commission for Jewish Affairs, the more confusing and ominous things get.

Klein’s request for information is met with resistance not assistance, and rather than clearing his name, his persistence leads to investigations and suspicion.

Some factual information eventually emerges, but the most compelling thing about “Mr. Klein” is its intentional air of mystification, that spelling everything out is not on its agenda.

Though it is filled with dramatic incidents, this is finally a dazzling film about mood, about creating an unnerving world where feeling safe turns out to be an illusion, where everyone is at risk whether they know it or not. If that doesn’t sound like a film for today’s world, I don’t know what does.

KENNETH TURAN, Los Angeles Times, OCT. 9, 2019

You should probably only read this essay after you have seen the film....lots of spoilers

“Mr. Klein,” a Political Mystery of Mistaken Identity in Occupied Paris.

The restoration and revival of Joseph Losey’s 1976 film “Mr. Klein,” screening at Film Forum today through September 19th, makes readily available a work that, like most masterworks, has a retrospective air of destiny but resulted from a series of useful accidents. Set in Paris in early 1942, during the German Occupation, it’s the story of a Parisian Catholic man named Robert Klein (Alain Delon) whose identity becomes confused with that of a Jewish man with the same name—and who, as a result, faces the same persecutions that Jews faced in France at the time.

Losey wasn’t the first choice to direct it; the project was meant for Costa-Gavras, a filmmaker of overt left-wing sympathies and a rather simplistic, albeit stirring, realistic manner, but he turned it down. Instead, Losey—also a leftist, but an aesthete of a different stripe—got the job. The resulting film is both a work of history, unstinting in its concrete depiction of political hatred and fear, and a portrait of the metaphysics of tyranny—a classic of doppelgänger paranoia that gathers the theme on a single string and pulls it into modernity.

There were many great directors working in Hollywood during the McCarthy era, but Losey was the great filmmaker of that era, whose movies of the late nineteen-forties and early fifties embodied the industry’s and the country’s political crisis, and did so in theme, in mood, and in style—and who then was forced, because of anti-Communist persecution, into exile. His first feature, “The Boy with Green Hair,” fused the pathology of racism with the terror of nuclear destruction; his film noir “The Prowler” was a bilious drama of surveillance, consumerism, predatory sexuality, and feral survivalism; his 1951 remake, on the streets of Los Angeles, of Fritz Lang’s “M” turned city life into a menacing web of observation and pursuit. He devised both a hectic manner of performance and a visual art to match: Losey’s screens are scarified and striated, a tangle of turbulent textures in which the characters are seemingly inescapably caught.

Losey went into exile in Great Britain in 1953 and continued his career (at first, with difficulty, and pseudonymously), making such Cold War masterworks as “Time Without Pity” (a story of a father and a son pitted against each other by a dubious arrest) and “These Are the Damned,” a.k.a. “The Damned” (a vision of post-apocalypse now). His romantic drama “Eva,” from 1962, starring Jeanne Moreau, renders intimate desperation as the distilled essence of modernity. Soon thereafter, he changed registers drastically, with “Modesty Blaise,” a hectic and giddily inventive espionage caper that’s adapted from a comic-strip series. He moved to France in the early seventies (fleeing British taxes) and made the chilly historical drama “The Assassination of Trotsky,” a French-Italian co-production with Richard Burton as the Bolshevik in exile and Delon as his designated killer, which hinted at the overarching tone of “Mr. Klein”—its sense of doom—if not its comprehensive imagination or metaphorical reach.

“Mr. Klein” starts with an act of genteel depravity that is all the more shocking for being historically true: a woman is being examined by doctors who are applying pseudoscientific methods (examining her gums and jaw, measuring her nostrils with a specially devised ruler, observing her naked body and her gait) to determine, in an official report, whether she is Jewish. The lone woman’s stifled indignation rises quickly to a collective silent uproar: the doctor’s waiting room turns out to be teeming with patients awaiting similar treatment. Along with the scene’s monstrous substance, Losey draws out its aftermath with an agonizing attentiveness to the specificity of time. The woman’s emergence from the examining room into the outer area, her reunion with her husband, who has undergone a similar examination, their exit past the distracted gaze of a pair of police officers, their passage through a long windowed corridor—silently, seeking a moment of privacy amid the relentless virtual surveillance of the state that is putting them through this intrusive sham and obscene ordeal—draw out the terrifying suspense of legalistic nonsense to an inconclusive void, setting the tone for the drama of Klein that follows.

As Anthony Lane mentioned in his review of “Mr. Klein,” Losey took on the project when another one—an adaptation of Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past”—fell through. Proust, who was Jewish, would have been seventy in the course of the events in “Mr. Klein,” and at the moment that Losey switched gears to the latter project, the title of Proust’s magnum opus, “À la Recherche du Temps Perdu”—“In Search of Lost Time”—was even more fitting for the Second World War and the thirty years of oblivion into which its horrors had sunk. The collaboration of French officials with the German occupiers was officially presented as a sort of aberration of individuals rather than a systemic corruption of French government and society. (In 1955, when Alain Resnais made the short documentary “Night and Fog”—about the struggle to recover memories of the Holocaust from the ten years of ordinary life and routine oblivion that, as he saw it, followed the end of the war—he was forced by French censors to remove an image of a French gendarme overseeing deportations.) At the time “Mr. Klein” was released, the ice was beginning to break, owing in significant measure to another film, “The Sorrow and the Pity,” a documentary by Marcel Ophüls, released in France in 1971, that revealed the extent of French collaboration with, even sympathy with, the occupiers’ anti-Semitic depredations.

As a film of wartime memory brought to life, of French history as intimate experience and vice versa, “Mr. Klein” did what a Losey version of Proust would likely not have done—it reckoned with experiences and actions that, far from being remembered, were actively denied, and it served as a sort of Proustian “Remembrance of Things Suppressed.” Klein is an art dealer living in the tiny Seventh Arrondissement, who doesn’t shrink from buying Old Master paintings from Jews in need of gold to flee the country. His machinations are heard before they’re seen, from the point of view of his lover, Jeanine (Juliet Berto), who overhears just such a perverse purchase from the sleek calm of her boudoir. Frightened by the appearance on his doorstep of an official Jewish newspaper, he heads to the newspaper office and then to the police station to clear up the mystery and instead learns that there’s a second Robert Klein, who lives at a different address—one that was scratched out on the journal’s mailing label and replaced with the first Klein’s own.

What results is a kind of detective story in which Klein’s search for the other Klein quickly becomes an existential search for himself. Meanwhile, uncanny traces erode his sense of who he himself may be. The police show up bearing his calling card, which he’d just given to a Jewish man from whom he’d bought a painting. He goes to the grubby apartment of the other Klein—let’s call him Klein II, as the filmmaker does in “Conversations with Losey,” a remarkable series of interviews conducted by Michel Ciment—and is physically mistaken for him, not for the last time. Seeking documents from his father in Strasbourg that would prove his family background, Klein instead hears some incidental remarks that cast doubt on the received certainty of the family lineage, and the longer it takes for some of the documents to turn up, the wider and darker the abyss of elusive selfhood grows.

Klein knows well the kinds of trouble that he faces when he’s mistaken for a Jew. It was, to say the least, a dangerous identity to bear in France at the time. France’s government, under the dictatorial power of Marshal Philippe Pétain, was expected by the Nazi occupiers to place restrictions on the country’s Jews—but Vichy France’s government went far beyond the occupiers’ demands in its persecution of Jews in its territory. The dire story was documented in detail in the groundbreaking 1981 book “Vichy France and the Jews,” by Michael R. Marrus and Robert O. Paxton, the second edition of which will be published on September 17th, with new information from belatedly opened French-government files. By 1942, Jews in France were excluded from the civil service and from many professions, including teaching and media, and from many universities (and were subject to quotas in others). Jews in France were subject to summary arrest; businesses owned by Jews were subject to confiscation, as was the personal property of Jews. Marrus and Paxton write that the regime sought nothing less than “to complete the exclusion of Jews from French public life.” Then, in 1942, Jews had to wear yellow stars on their outer garments, to mark them conspicuously; mass deportations of Jews in France began, too, organized not by the German army or the Gestapo but by French police officers and French officials.

The fragile fiction of Klein’s identity is matched by the fragile illusions of his social whirl. He practices intimate deceptions. He deceives Jeanine about money; his former lover, Nicole (Francine Bergé), the wife of his lawyer, Pierre (Michael Lonsdale), about love; a concierge (Suzanne Flon) about his effort to enter Klein II’s apartment; and Klein II’s lover, Florence (Jeanne Moreau), a Jewish woman in a rural château, about his pursuit of his double. (Meanwhile, these characters pull off suave deceptions of their own.) Getting hold of a photograph from Klein II’s apartment, Klein rambles through the city, backstage at a cabaret and to the outskirts of town at a munitions factory, in pursuit of another woman in Klein II’s life. A piece of string that turns out to be a bit of detonator cord tips Klein off to the Klein II’s involvement with the French Resistance—a recognition that, for our protagonist, sets his drama on a grander historical stage. Meanwhile, the gloss of society continues unabated but with a weird air of grotesque distortion: diners at a celebrated café stuff their faces, alongside festive German officers, with a frantic zeal at a moment when the country at large endures food shortages. A night-club act, with its elaborate stagecraft, turns out to be a work of anti-Semitic propaganda. An ordinary café bears a sign banning Jews from its premises.

The illusions that Klein confronts in the course of the film are the illusions of his divided and compartmentalized consciousness—the self-deceptions of individuals pretending that there’s anything like normalcy while the depredations of surveillance, arrest, and deportation occur. There’s a notable moment when specially labelled buses, filled with deportees, many wearing the yellow star, pass by an outdoor produce market filled with shoppers going about their business. Losey draws out the time of such scenes. The simple passage of time—under threat, in doubt, and in silence—creates an unbearable dramatic suspense, and Losey catches it in motion, in ordinary actions that seethe with menace and doom. He sets the camera roving and wandering through corridors and streets, shifts points of view to catch multiple simultaneous levels of suspicion and surveillance, fills lavish interiors with geometrical jumbles and clashes of color and shape that evoke a relentless screech of distraction and diversion, and even finds, in the incongruous dense leafiness of a rounded tree in a city street in the dead of winter, a texture of hypnotic distraction. The very forms of the city’s sights, as in the filigreed glasswork in the Grand Palais, requisitioned for police actions—a glorious structure built in the heart of Paris at the exact time that the anti-Semitic fury of the Dreyfus affair was raging—evoke the snares and nets, the cagy concealments, that define the modern history of French public and political life.

The spectacle of “Mr. Klein” is that of the absurd rendered ordinary, of the senseless depicted as normal. Its drama of willful obliviousness is elevated, through Losey’s aesthetic, into a cinematic ontology. There’s an exchange, in Primo Levi’s “If This Is a Man,” in which he asks a concentration-camp guard “Why?” The answer is, “Hier ist kein Warum”—“Here there is no why.” There is certainly a “how,” though, and Losey doesn’t stint on it, showing the mighty mechanism of documentation, of police files, on which the bureaucratic machinery of murder depends, and also the organized police activities, the meetings, the maps, the banal physical labor of signage and partitions, the dispatch of unmarked cars, the coördinated timing of raids, the relentless interrogations, and, ultimately, the bare brutal use of force. At the time of the movie’s release, France was still decades away from admitting its responsibility for its anti-Semitic persecutions and murders during the war. The illusions that Losey revealed weren’t just those to which Klein was initiated but those of France at large, a country that, at that very moment, was a mere simulacrum of itself. No less than Losey’s McCarthy-era movies and Cold War productions, “Mr. Klein” is a political movie in the present tense.

Richard Brody, September 6th 2019

What you thought about Mr Klein

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 (29%) | 19 (54%) | 6 (17%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 35 Film Score (0-5): 4.11 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

104 members and guests attended. Only 35 responded giving a hit rate of 30% and a film score of 4.11.

Your collected comments are below.

"The combination of mid seventies cold war paranoia reflected upon the morally murky hall of mirrors of Vichy France makes for a queasily discomforting movie. All fixed points are gradually unmoored to leave us drifting, ever more uncertain, as the authoritarian walls press inwards. The gradual unhinging of the amoral but complacently confident Delon is the the stuff of Kafka and Borges and convincingly done, all more explicable at the finale than it is during viewing. In that respect it feels modern - it is territory Christopher Nolan and Guillermo del Toro inhabited before their budgets went through the roof. The end, when the scale and impersonality of the Nazi meat grinder is revealed is quite shocking. All the more so as it seems discomfortingly relevant. The film stays in the mind like a bad dream, hard to forget but not easy to like".

"Thought provoking. Can understand why the French were not very happy when the film came out, shines a light on some shameful collaboration (fyi saw "Good" by C P Taylor two days later - National Theatre Live - made a very interesting companion piece to this film...). I still can't figure out why he made the choice at the end of the film though".

"A splendidly visual and sumptuous set which I travelled through luxuriously until the bite came - exploitation of human beings and finally destruction!! Was the young girl playing The Internationale on the piano?"

"Not always easy to follow or some scenes to watch but a compelling film and incredible to learn of the French complicity in rounding up Jews in the Second World War. Alain Delon was outstanding in the role. Does anyone know what the very annoying beeping noise throughout the film was? Thanks for another interesting choice".

"A most elusive, almost scary film that kept a grip yet not violent or horrific. Kafka and Orwell come to mind with the triumphalist radio celebrating victorious Phalangists, sinister mobilisation of troops and gendarmerie Kafka-esque curtained interview rooms. Delon's character thinks nothing of frequenting a café sporting anti-Semitic signage, contrast with his struggle to sort out family certification makes him realise the depth of his position. Ideas about identity, privilege, and then empathy; Klein is someone who levers his life of conveniences in order to survive and we never really find out his dilemma. Losey's precision in showing this is subtle through the film's tone, mysterious mistaken identity, quite standard tense metaphors: Internationale being played to remind us of Losey's politics Thought the narrative has a certain vagueness, so we have to put the puzzle together. Dark humour evident as well, some elegant framing gives the kind of film that needs seeing again"

"An interesting story of exploitation and karma during WW2".

"Beautifully shot and assembled. Terrifying".

"I felt that there were a few gaps in the plot, but still very enjoyable. I thought the opening scene of the woman's physical examination was very moving. The closing scenes of the roundup of Parisian Jews was heart breaking".

“Excellent cinematography, very atmospheric original story”.

“Visually stunning. Powerful story”.

“Very moving…beautifully made”. “Excellent…enigmatic ending”.

“Got lost & I didn’t follow the plot. But gripping nonetheless”.

“Excellent photography – gripping”.

“Powerful but often confusing. Excellently filmed with a very strong musical score. Alan Delon at his most dashing”.

“Based on an actual round up by the French police- the Jews were kept in the Velodrome in Paris, no water, many died – a source of shame as McCarthyism must be to Americans”.

“A most intriguing plot – I wish I could have understood it!! A story of time told so brutally”.

“Very puzzling”. “Atmospheric, moody & very confusing. The ending was upsetting”.

“Very powerful ending”. Very powerful. Slow start. Unusual and will probably start a few conversations”.

“Strange. Of its time but fascinating”.

“What was the annoying high-pitched beep all the way though? Very atmospheric, chilling in the extreme. A little slow! Good to see Delon and Moreau – love a French film. Beautifully realised”.

“Well acted and atmospheric, but a bit slow at times”.

Very good and atmospheric – makes more use of the Vichy Government at the time. Lovely views of Paris and interiors”.

“Beautifully photographed but I lost my way at times. Disturbing too”.

“The end was disappointing”.

“Second half better than the fist which was confusing! Devastating final scene”.

“Not sure I completely got all the fine points of the story. Great filming and atmosphere”.

“A melodrama/ a thriller/ a reflection on identity/ a moral tale – felt it was a bit confused about what it was”.

“I found it difficult to follow the plot and piece together the action. Excellent photography and costumes”.

“Good in parts but confusing”.

“Couldn’t follow the story line”. “Tedious”.