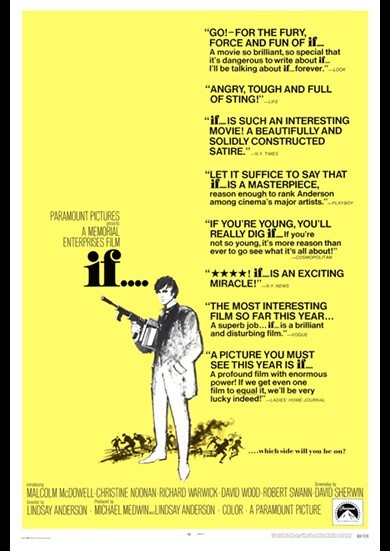

If

Mick Travis (a young Malcolm McDowell) returns to his public school, caught between the sadistic older boys known as the Whips and the first-year students, known as Scum, who are forced to do their bidding. The petty thefts and anti-social behavior of Travis and his two henchmen, Johnny (David Wood) and Wallace (Richard Warwick), soon attract the attention of both the Whips and the school's out-of-touch administration, and lead to an unexpected showdown.

Film Notes

"IF . . ." is so good and strong that even those things in the movie that strike me as being first-class mistakes are of more interest than entire movies made by smoothly consistent, lesser directors. Lindsay Anderson's second feature (his first, "This Sporting Life," was released here in 1963) is a very human, very British social comedy that aspires to the cool, anarchic grandeur of Godard movies like "Band of Outsiders" and "La Chinoise."

As an artist, however, Anderson, unlike Godard, is more ageless than young. He was born in 1923. His movie about a revolution within a British public school is clear-eyed reality pushed to its outer reaches. The movie's compassion for the individual in the structured society is classic, post-World War II liberal, yet "If . . ." is also oddly nostalgic, as if it missed all that sadism and masochism that turned boys into adolescents for life.

Mick and his two roommates, Johnny and Wallace, are nonconforming seniors at College House, a part of a posh boarding school that is collapsing under the weight of its 1,000-year history."Cheering at college matches has deteriorated completely," warns the student head of College House."Education in Britain," says the complacent headmaster a little later, "is a nubile Cinderella, sparsely clad and often interfered with."As the winter term progresses through rituals that haven't varied since the Armada, Mick, Johnny and Wallace move mindlessly toward armed rebellion.

On Speech Day, armed with bazookas and rifles, they take to the roofs and stage a reception for teachers, students and parents—and at least one Royal Highness—comparable to that given by Mohammed Ali to end the control of the Mamelukes.

I can't quarrel with the aim of Anderson and David Sherwin, who wrote the screenplay, to turn the public school into the private metaphor, only with the apparent attempt to equate this sort of lethal protest with what's been happening on real-life campuses around the world. Revolution as a life style, as an end in itself, is the fundamental form of "La Chinoise," but it's confusing and too grotesque to have real meaning attached to what is otherwise a beautifully and solidly constructed satire. In such a conventional context, the revolutionary act becomes one of paranoia.

Anderson, a fine documentary moviemaker, develops his fiction movie with all the care of someone recording the amazing habits of a newly discovered tribe of aborigines. The movie is a chronicle of bizarre details — Mick's first appearance wearing a black slouch hat, his face hidden behind a black scarf, looking like a teen-age Mack the Knife; the hazing of a boy by hanging him upside down over (and partially in) a toilet bowl, and a moment of first love, written on the face of a lower form student as he watches an older boy whose exercises on the crossbar become a sort of mating dance.

As a former movie critic, Anderson quite consciously reflects his feelings about the movies of others in his own film. "If . . . ," an ironic reference to Kipling's formula for manhood, uses a lot of terms most recently associated with Godard. There are title cards between sequences ("Ritual and Rebellion," "Discipline," etc.), and he arbitrarily switches from full color to monochromatic footage, as if to remind us that, after all, we are watching a movie.

There is also an enigmatic girl (Christine Noonan), a waitress picked up at the Packhorse Cafe, who joins the revolt. Miss Noonan suggests a plump, English, mutton-chop version of Anna Karina, even without looking much like Miss Karina.Less successful are visualized, split-second fantasies—or what I, take to be fantasies. When the three boys are told to apologize to the chaplain for having attacked him during a cadet field corps exercise, the headmaster withdraws the chaplain's body from a morgue-like drawer.

The fantasies just aren't very different from a crazy, believable reality in which a master's inhibited wife wanders nude through a deserted dormitory, lightly caressing objects that belong to the boys.

The movie is well acted by a cast that is completely new to me. Especially good are Malcolm McDowell (Mick), who looks like a cross between Steve McQueen and Michael J. Pollard; Richard Warwick (Wallace), Peter Jeffrey (the headmaster), Robert Swann (the student leader) and Mary McLeod (the lady who likes to walk unclothed)."If . . . ," which opened yesterday at the Plaza Theater, is such an interesting movie (and one that I suspect will be very popular) that the chances are there will not be another six-year gap between Anderson features. After making "This Sporting Life," Anderson worked in the British theater and turned out two shorts, "The White Bus" and "The Singing Lesson," which will be shown here at the Museum of Modern Art April 30.

Vincent Canby, New York Times,

Although it openly lifts the plot and symbolism of Jean Vigo's 1933 "Zero de Conduit", a film that was considered so incendiary that the French authorities banned it until 1945, "If..." is a true British classic.

Taking Vigo's movie as its starting point, "If..." taps into the revolutionary spirit of the late 60s. Each frame burns with an anger that can only be satisfied by imagining the apocalyptic overthrow of everything that middle class Britain holds dear.

Malcolm McDowell heads the cast as Mick, a teenage schoolboy who leads his classmates in a revolution against the stifling conformism of his boarding school. Facing up to the bullying prefects and the incompetent teachers, Mick and his crusaders attempt to destroy the stagnant system of petty viciousness and an out-dated belief in the importance of the institution over the individual.

Anderson captures the spirit of youthful rebellion beautifully, linking it with the sweeping political changes that were dominating the headlines through the photos of Mao, Che Guevara, and Vietnam that adorn the walls of Mick's bedroom (shooting started just a few months before the May 1968 riots in Paris).

The film's greatness lies in its surreal take on these events. As the schoolyard revolution slowly kicks into gear, the film itself begins to disintegrate. The photography switches restlessly between colour and sepia, and the narrative becomes increasingly elliptical as reality and fantasy merge.

The years may have robbed it of some of its power, but "If..." still deserves the reputation as one of the best films to have come from these shores, a subversive, anti-authoritarian masterpiece that stands alongside Godard's "Weekend" and Bunuel's "The Exterminating Angel" as a blistering attack on the morality and values of the middle class. To rework that famous Parisian cry of 1968: "Under the schoolyard, the beach!"

Jamie Russell, BBC Radio Times,, 26 February 2002

What you thought about If

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34 (57%) | 19 (32%) | 5 (8%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 60 Film Score (0-5): 4.40 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

98 members and guests attended this screening. We received 60 responses giving a hit rate of 61% and a Film Score of 4.40. An excellent response rate thanks so much.

All of your responses are collected below: -

“Michael made a comparison to Godard's 'Weekend' in his introduction which I had not previously considered and was unconvinced by until the film was shown. They're indeed similar but what I had not appreciated was what a very, very angry film this is. I first watched it as a 14 year old grammar school boy and loved for its thrilling and provocative finale. Perhaps, back in the seventies we were inured to film of public schools and their traditions ('Tom Brown...', etc), probably I was less politically aware but this now seems incandescently furious with the cruelty, misogyny, throttling of any individuality or creative impulse of the public school sausage machine, pumping out identikit repressed and malformed men to run the Empire. I dare say, at the time, that it might have been assumed that this system was on its last legs. Boris and his self serving lackeys know otherwise. This seems more relevant now than then. Remarkably it also manages to be quite funny, if the tone is uneven and the more fantastical sequences don't entirely work it matters not, its righteous fury shines through”.

“Wish I didn't have such responsive mirror neurons….so that I didn't feel each act of mindless cruelty! Very shocking and brilliantly done”.

“A powerful film and a damning condemnation of a system that still plagues this country.

“It was great to see a classic of British cinema - especially as I'd missed it first time round, although I was at university when it was released! GFS should have at least one classic of this sort every season (maybe you already do). I'd rate it Excellent by the standards of 60's films, although only Good by today's. As a satire on the public school system, it was excellent, and I recognised much from my own school, although sadly, not nearly as outrageous as "If...." would have you believe. I was not the only one puzzled by the occasional B&W sections, which didn't seem to coincide consistently with Mick's fantasies. But one can see why McDowell, alone among the younger cast members, went on to such greater things and also, alone among most of all the cast members, is still alive and working”.

“Struck by how well this holds up after over 55 years; still unsettling even with its dark bitter humour. Remains a strange film shining a light the excesses of boarding school life as a microcosm of society to demonstrate the repression of the individual by authority. Reminded me of Zéro de conduite. Recall that Lord Brabourne called it 'the most evil and perverted script I've ever read. It must never see the light of day'. Hmm ... It's culturally significant in its distinctive 'Englishness' and part of the shift in film making in GB in late '60s . Liked the slow start, feeling of being stuck, just like the boys at the boarding school with rituals so students feel like herded cattle. Gradually, though, audio and visuals become more impressive. especially oft-repeated and quite stirring Sanctus by Missa Luba, a joyful counterpoint to the stuffy hymns suffered by the schoolboys in chapel. Then it spirals into fantasy and mutiny, driven with a larger sense of agitation and discord.

Thought that McDowell as Travis (bright and clearly able) has borderline sociopathic tendencies is, undeniably, incredibly creepy, yet charming. The random black and white scenes (economics of film making?) give rise to an ambiguous tone, similar fantasy sequences scattered throughout (the chaplain in a drawer, the naked woman at the cafe, the housemaster's wife wandering the empty corridors, and possibly the ending) - ambiguities seamlessly combined with the 'real' moments make it a compelling watch. I'm a sucker for Anderson's work anyway, and how he presents aspects of Britain in the '60s through to the 90s. Felt its bitter and enigmatic approach pointedly - and perhaps frustratingly - refuses to come down on the side of either its problematic protagonists or the self-serving patriarchy they are fighting against. The beating scene makes the narrative increasingly fragmented until the final chapter "Crusaders" is striking and powerful in its direct execution. "If....," and Kipling's ode to British stoicism and stiff upper lips resonates and responds with a sarcastic nod”.

“Great to see this subversive British film on the big screen again. Less is more, seems to be Lindsay Anderson's film output; very few feature films made by him but always enjoyable to watch. Only gripe is that some of the speaking was too soft to hear properly. Hope you have room for a John Boorman feature in the future….”.

“A wonderful snapshot of the British 'New Wave'; Mr Anderson giving both barrels to his old school. Must have been quite shocking in its time but still impactful today. Keep these classics of cinema coming!”

“Started a bit like Tom Brown's Schooldays then got progressively weirder! Probably my least favourite film of the season so far, but even so it did have redeeming features in some of the acting, plot lines and humour and as a result it was highly watchable. I'm sure there are many ex public schoolboys who would have liked to have done what the revolutionaries did at the end! Not particularly my cup of tea but glad I saw it and that for me is part of what being a member of the Film Society is about. Thanks”.

“I found the film still relevant in its challenge of ' the establishment' & still enjoyed the surrealism, dark humour & uncertainty of what did or did not actually take place...”.

“Still think it is a great film & that it is it is still relevant. Darkly humorous, surreal , shocking”.

“Of its time, If was an important and revelatory film - set against the backdrop of the new freedoms of the 1960's, it exposed much of the appalling cruelty and bullying that existed within the English public school system. A shocking ending with a somewhat complex narrative - but well worth revisiting”.

“Not my taste and didn't really enjoy the insight and brutality of private education as portrayed in the film”.

“Fabulous film. Happy laughs. Greats actors and actresses’”.

“O Lucky Man? – more French films?”

“Love the mix of Black and White with colour on the film. Violence, religion and old school – a vision combined with sound conjures up the smell”.

“Brilliant film, very much of its time but still excellent today”.

“Excellent. So well portrayed. It caught the mood of those schools: stifling, unnecessary discipline”.

“Surreal and captured the testosterone of a boys public school in the 1970s. Those boys are now called boomers - born in the 50s., they would of course make great Rogue Heros. Thanks”.

“Absolutely brilliant. More Lindsay Anderson please and films from this era”.

“Brilliant”. “Real classic. Enjoyable and thought provoking”.

“Brilliantly ridiculous – Pythonesque even!”

“Yes, IF is a very disturbing film. why would you send your children to a school like that?”

“Equally shocking today as when it first me out!”

“Very thought provoking and too much to think about”. “Still excellent”.

“Understandable. Terrific and acting”.

“Although I had to really concentrate, I admired the surreal elements. Very clever”.

“Remarkable – just as powerful and justified as on the first viewing”.

“Sublime! Extraordinary!!”

“Thought provoking. Must have been a revelation in 1969. Now explains a lot”.

“Liked the film, but a strange end”.

“Still fresh and relevant”.

“Watching it at 19 and at 70+, is a quite different experience”.

“I first saw this shortly after it was released and it still has the same impact it had then”.

“Lord of the flies meets St Trinians – not so much if…...as Why?”

“(Sound quite distorted). It was quite extraordinary! Shocking! Compelling!”

“A little dated in its approach but still very powerful. Funnier than I expected”.

“Difficult to understand. Will need to investigate why “IF”.

“Some interesting satire and surrealism but overall seemed unaware of its privilege whilst dissecting privilege. Some amazing performances and funny at points, but felt disjointed overall. Perhaps a general response - or a millennial, I recoiled at moments those around me laughed”.