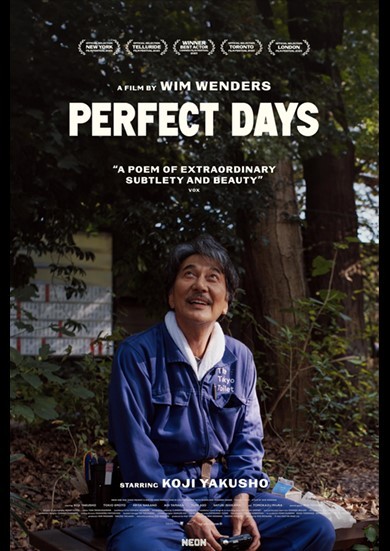

Perfect Days

Hirayama works as a toilet cleaner in Tokyo. He seems content with his simple life. He follows a structured everyday life and dedicates his free time to his passion for music and books. Hirayama also has a fondness for trees and photographs them. More of his past is gradually revealed through a series of unexpected encounters.

Film Notes

‘Perfect Days’: Cannes Review.

Wim Wenders returns to Cannes competition with this meditative tale of a man living a quiet existence in Tokyo.

Japan has previously brought Wim Wenders inspiration, in 1980s documentaries Tokyo-Ga and Notebook On Cities And Clothes. Now, the German veteran returns to Tokyo to reinvent his fiction film-making (and, to some degree, retrieve his mojo) in Perfect Days, a likeable, elegantly crafted drift that might superficially seem as close as they come to being the proverbial ‘movie about nothing’. In fact, this is a philosophical contemplation that is very much about something – a meaning-of-life film, no less – with an introverted, immensely likeable central performance from Koji Yakusho. Wenders’ Cannes Competition entry is likely to be his most commercial fiction in some time, despite being unapologetically an art-house miniature. Yet it’s hard to escape a certain preciousness that is likely to turn off viewers with harder-edged tastes.

This is a film about a solitary man – Hirayama, a toilet cleaner in late middle age, played by Japanese cinema mainstay Yakusho, who won the Best Actor prize at Cannes. A low-height Ozu-style shot at the start shows Hirayama waking in his sparse flat before he shaves, trims his moustache, sprays his houseplants and dons the blue overalls of Tokyo Toilets, the company he works for. Much of the film shows Hirayama cheerfully and meticulously going about his work, sometimes accompanied by his erratic young assistant Takashi (an abrasively goofy comic performance by Tokio Emoto) and listening to pop cassettes as he drives his van. In between, we see the uneventful but contented flow of his days: relaxing in a bathhouse; eating in various bars, where he eavesdrops with amusement on customers’ banter; reading William Faulkner; and taking photos of the world around him with an old-fashioned film camera.

The taciturn Hirayama barely speaks throughout – Takashi rates him “9 out of 10 on the weirdness scale” – but he is no discontented recluse, simply someone who appears at ease in a world that he is alertly aware of. He does not need to socialise but seems happy enough when he comes into contact with people; like a small boy he rescues, and Mama (Sayuri Ishikawa), a middle-aged woman who runs a noodle bar he frequents. It’s only later in the film, when he is visited by teenage niece Niko (Arisa Nakano), that we get some glimmer of his background, with the suggestion that he has cut himself off from his roots.

In fact, another relative expresses shock that Hirayama is working as a toilet cleaner – which might hint at a life-choice trajectory akin to the Jack Nicholson character in Five Easy Pieces. But the job itself isn’t at all represented as menial drudgery, and what another film might have depicted as a lonely, meaningless existence here comes across as very meaningful and quietly rich. (Among recent films, the closest affinity in subject and tone might be Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson). As well as a sensitive, spiritually-attuned observer of the world, Hirayama is a perfectionist who takes pleasure in leaving his conveniences immaculately tended (admittedly, Wenders skews the picture by having him only tend to Tokyo’s shiniest, most architecturally appealing loos, like the one with glass walls that turn magically opaque at the turn of a doorknob).

When Hirayama goes to sleep, we see his dreams; semi-abstract superimposition montages in black and white (the director’s wife Donata Wenders is credited with ‘dream installations’). An end title explaining the Japanese concept of komorebi (roughly, the dappled shadows of leaves) wraps up some key themes, although perhaps too explicitly after Hirayama’s playful encounter with a melancholy divorced man (Tomokazu Miura, from Takeshi Kitano’s Outrage films, among others).

The film is liberally punctuated with music, primarily 60s pop, but it’s surprising that Wenders, always noted as a jukebox connoisseur, should have opted here for such a clichéd Golden Greats selection – Nina Simone, Van Morrison, ‘House of the Rising Sun’ (also sung by Ishikawa in a Japanese version), even Lou Reed’s ‘Perfect Day’, making the title connection a touch obvious. By contrast, welcome exceptions include Patti Smith’s ‘Redondo Beach’ and the Rolling Stones rarity ‘(Walkin’ Through The) Sleepy City’.

Very much in the film’s favour are its lazy drift, its refusal of restrictive narrative shape and its restless exploration of Tokyo, with Franz Lustig’s photography luminous by light and day. Some familiar Wenders references are here (notably a nod to Patricia Highsmith’s fiction), while the Ozu influence is inevitably present – although the overall tone is closer to latterday reference points like Hirokazu Kore-eda, in his softer mode, and Naomi Kawase’s delicately feelgood Sweet Bean. An extended shot of an ambiguously smiling Hirayama is a closing grace note but, for all its poetic charm, this is a slender work that comes across as something of a ’mindfulness movie’, in a faintly self-satisfied vein.

Jonathan Romney, Screen Daily, 25 May 2023

‘Perfect Days’ Review: Wim Wenders Finds Beauty in the Quotidian in Exquisite Japanese Drama About Gratitude

Distinguished screen veteran Koji Yakusho plays a middle-aged Tokyo man who has pared down his life to a routine of service and small pleasures in this delicate character study.

Holding an extended closing shot on a character’s face has often been an effective way to illuminate whatever thoughts and feelings are running through their head, to keep them resonating through the end credits and even beyond. The device worked exceptionally well in Call Me by Your Name, Benediction and Michael Clayton.

Wim Wenders ends his eloquent and emotionally rich Japanese drama, Perfect Days, with such a shot, held tight on the extraordinarily expressive face of Koji Yakusho as his character drives through Tokyo reflecting on the rewards and perhaps also the regrets of his life with the same spirit of openness and acceptance, embracing the sadness as much as the joy.

The song that this resolutely analog man is listening to on his car cassette player is a Nina Simone standard that has become one of the most overused tracks in contemporary movies. But it fits the scene so precisely and captures the way in which the character moves through his small pocket of the world with such exactitude, it feels almost like hearing the song for the first time.

Almost four decades after retracing the footsteps of Ozu in the documentary Tokyo-Ga, Wenders returns to the Japanese capital to make his best narrative feature in years. Enriched with a vivid sense of place, the film takes its cue from the Japanese word komorebi, which describes the shimmering play of light and shadows through the leaves of a tree, every flickering movement unique.

Around that modest flourish of nature, the director has crafted a film of deceptive simplicity, observing the tiny details of a routine existence with such clarity, soulfulness and empathy that they build a cumulative emotional power almost without you noticing. It’s also disarming in its absence of cynicism, unmistakably the work of a mature filmmaker thinking long and hard about the things that make life meaningful. Perhaps a solitary life more than any.

The life at the center of every frame — heightened in intimacy by the snug 1.33:1 aspect ratio — is that of Hirayama, played by Yakusho with relatively few words but a bottomless well of feeling. He has what’s seemingly the least likely job for the protagonist of a contemplative two-hour movie — working for a private contractor cleaning restrooms in public parks in the Shibuya district. The company’s unambiguous name, The Tokyo Toilet, is emblazoned in white across the back of Hirayama’s blue overalls.

The first thing worth noting about this job is the actual toilets. These are not your average public facilities in most Western countries but architecturally distinctive structures that from the outside could almost pass for small temples or shrines. Which makes it fitting that Hirayama approaches his work with monastic discipline and scrupulous dedication.

Unlike his lazy junior co-worker Takashi (Tokio Emoto), who arrives late and is usually too distracted on his phone to do a thorough job, Hirayama has a methodical system and a series of products and essential cleaning tools for all tasks packed in his van. There’s something quite touching about the way he promptly steps outside and stands patiently whenever anyone needs to use the facilities while he’s working.

To most people, Hirayama is invisible. But one of the points of the film, written with great clarity and economy by Wenders and Takuma Takasaki, is that even the most humble, invisible life can contain spiritual riches.

That aspect is evident instantly in the transfixing opening sequence, in which Hirayama wakes at dawn to the sound of an old woman sweeping the streets with a birch broom outside his window. He swiftly folds his futon and stacks his bedding neatly in a corner, brushes his teeth, shaves and trims his mustache, then mists his plants, taking a moment to sit back and smile at their progress. He smiles again as he steps outside each morning and looks up at the sky.

This fascination with the most ordinary daily rituals inevitably recalls Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. The sense of a life stripped of clutter, boiled down to essentials in acts of both duty and pleasure, continues throughout Hirayama’s day.

He chooses a cassette from his extensive collection of ‘60s and ‘70s rock to listen to in his van (allowing Wenders to pepper the movie with Lou Reed, The Rolling Stones, Otis Redding, The Animals, The Kinks and more). He eats his lunch on the same bench in a temple garden every day, taking a photograph of the same patch of light through treetops on his analog camera. After work, he hits the local sento bathhouse for a scrub and soak and eats dinner at the same market food counter.

At home again in the evening, the routine continues, ending with him reading a paperback he picks up from the dollar rack at a bookstore (in one of many nice touches of gentle humor, the store clerk offers unsolicited opinions about his choice of authors: “Patricia Highsmith knows everything about anxiety”). When Hirayama switches off his reading lamp and removes his glasses to sleep, he dreams in black and white sequences that hint at a more complicated earlier life, fragments of it filtered through leaves.

There’s a soothing aspect to the gentle rhythms of Hirayama’s day, which with each repetition reveals subtle differences. His direct interactions with other people invariably are acts of kindness, and he treats everyone with the same spirit of generosity.

That applies even to annoying Takashi, who in one amusing scene ropes his senior colleague into helping in his frustrated efforts to date the much cooler Amy (Aoi Yamada). The way Amy responds to the Patti Smith album, Horses, and in particular, the song “Redondo Beach,” while Takashi barely pays it any attention indicates that she will remain out of his reach.

While Emoto’s performance is a little broad compared to the restraint of everyone else in the cast, the excitable Takashi serves to show that not everyone is a smooth fit for Hirayama’s orderly world.

When Hirayama’s routine is disrupted and the careful balance is upset, notably when he’s forced to cover the work of two employees one day, we sense how rarely he lets moments of anger overcome him. The sudden appearance of his niece Niko (Arisa Nakano) after a fight with her mother initially requires some adjustment, but scenes in which he folds her into his workday — reluctantly at first, and then happily — are captivating depictions of two generations connecting.

The emotional tug of the movie is never obvious, mostly creeping up on you almost imperceptibly. Chief exceptions, when Hirayama’s feelings are laid bare, include a private moment between the owner of the restaurant he goes to on his day off, known as Mama (Sayuri Ishikawa), and her ex-husband (Tomokazu Miura), with whom he later shares a beer by the river. And an encounter with his estranged sister Keiko (Yumi Aso) when she comes to take Niko home suggests the affluent life and family friction Hirayama left behind, while stirring up feelings of sadness and lost affection that remain with him.

The real reward of Perfect Days, however, is the accumulation of tiny details, tenderly observed fragments of a life that on their own seem inconsequential. When pieced together, they create a poetic, deeply moving account of the unexpected peace, harmony and contentment that one man has worked hard and made difficult decisions to attain.

What you thought about Perfect Days

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32 (51%) | 18 (29%) | 11 (17%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 63 Film Score (0-5): 4.27 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

105 members and guests attended this screening. The total number of responses was 63, giving a film score of 4.27 and a response rate of 60%.

All of your comments are collected below.

“I loved this film- beautifully simple yet enigmatic with a wonderful central performance. Top marks”

“This is an immensely bold, mature slice of cinema. It is also, at times, quite dull and repetitive. Wenders has the confidence to keep us in the loop of Hirayama’s precise and controlled life for a very long time, drip feeding us occasional gentle moments of comedy and beauty but giving us no narrative to speak of until, in a single short scene, there is an implied explanation of his situation. The relative tedium of the previous 80 minutes gives this shocking revelatory weight and pathos and transforms the film completely. That none of it is explicit just makes it more powerful. In the first section we understand that the apparently serene Hirayama takes pleasure in the precision of the requirements of his work, is not irked by its nature and is able to savour the small moments of beauty that surround him. After this we see that perhaps this is because he has been the scion of a great house but has fallen from grace, possibly via drink, and that he is living in the recovering addict’s world of ‘one day at a time’ and so is comfortable living in the now; ’Now is now’, and needs the rigour of his routine to give him purpose. His serenity is hard earned and requires management. A beautiful, thoughtful film and an outstanding performance from Yakusho”.

“A real gem of a film wonderfully depicted by Yakusho showing how his orderliness at home translated into that of cleaning 5* toilets in Tokyo - we can only dream of just having public conveniences in the UK let alone quirky & clean ones and anyone willing to clean them! Despite little dialogue Hirayama brings the film to life with his humble and gentle nature, supported brilliantly by the rest of the cast and with the fabulous soundtrack and cinematography, it made this a truly memorable & enjoyable film”.

“A wonderful life affirming film. Isn't contentment what we all aspire towards in life and this film depicts that beautifully”.

“A splendid film. A combination of great acting and perfect pacing of a fully credible story”.

“Enjoyed the music, film very slow not really sure what it was trying to illustrate”.

“Very enjoyable and thought provoking. A simple life portrayed showing an easy warmth and gravitas. Think that Wenders (a favourite director of mine!) allows Yakusho to lead the movie, with supportive direction. In films like Paris, Texas and Lisbon Story, he creates some striking compositions both natural and architectural – the range of toilet designs (like works of art, maybe?) on Hirayama's route are a highlight, as well as the trees' canopies. Wenders suggests, quietly and unswervingly, a beauty in the every day, shown in most scenes, yet doesn't give the viewer all the answers. Mundane maybe but contentment in everyday life - the music cassettes, the light between the trees where he has his lunch, companionship of those he passes daily. Hirayama is taciturn but friendly to his brash colleague, warm to his niece, yet conveying much in a single glance. Could argue, though, that Wenders wants to take us back from a surveillance dystopia and the city's overpowering nature through a film camera and tapes. It's in this that Hirayama finds peace in a world that may seem intrusive. Is it too sentimental? But Wenders encourages us to think of the world around us, while showing a reverence for Tokyo and Japan more broadly. It's a good example of a commitment to how significant is the ordinary”.

“10 out of 10 for me on the Takashi scale! Who'd have thought a film with so many toilets being cleaned could be so charming and absorbing, primarily of course due to the delightful nature of Hirayama and his simple life. Wish the public toilets around here were as special as those in Tokyo and a great score too. Another excellent choice, thanks”.

“I loved this gentle film. Live a simple life and enjoy nature around you. Great soundtrack”.

“All our inconsequential lives are full of meaning. I don't believe this. But it seemed plausible for the 124 minutes of this film. What fabulous toilets Tokyo has”.

“Beautiful filming. Main actor has a wonderful expressive face".

“Can't make up my mind if it was too slow, or if the repetitive scenes were mesmeric! Delightfully unclear about his previous existence and why he left it for the pride he took in his new work”.

“Main Actor was phenomenal but it was just too drawn out. We’re in a new era- I don't have the attention span for something like this anymore”.

“Quite marvellous”. “Excellent all around”.

“I liked this film very much. A beautiful film. I liked the way his life of routine contrasted with people who came into his life or crossed his path, his niece, the homeless man. I loved the music”.

“Beautiful to watch and listen to. Very well acted”.

“What a very enjoyable film. Such a simple, laid back story of everyday life of an ordinary man”.

“You were right about the score”. “Extraordinary”.

“A masterclass in direction and editing. I really enjoyed the music!”.

“I did enjoy the simplicity of this film. A man with a menial job and with great pride in doing it well. There was something of an innocence about him. The contrast being his sister’s life. Great music”.

“Delightful”.

“What an actor! Beautiful filming and I loved the daily life and how content he was – when I go to Tokyo, I want the loos cleaned by him!”

“Unusual film, very engrossing and subtle”.

“I personally loved this movie. The beauty of timing each moment, every day”.

“I love Japanese films. Always gives insights into human nature and positive about life regardless of situation/trapped in role”.

“Enjoyable and fascinating”.

“The nobility of low status work and monotonous routine!”

“A very good film”. “No gloves”. “Too long”.

“A most unusual film. I’ve always wanted to see Tokyo – and now I have. It reminded me of a Japanese student who came to live with me for a month as I’m an English teacher. He wanted to learn how to ‘feel’ – we sang every day and walked in the woods! It worked!”

“The main actor had a warm face”.

“Good but!! A bit too slow. Whereas Freemont contained more emotional impact as the girl was searching and he was avoiding”.

“Kept waiting for something to happen…..”.

“A nice gently paced film, if a little repetitive”.

“I could not fully connect to the emotional ambition of the director’s script”.

“no story line so extremely slow. But excellent acting and a really uplifting ending”.

“Confused and puzzling…….”.

"Wenders must have seen it as a challenge to see if he could make the endlessly repeating days of a toilet cleaner interesting – don’t think he succeeded. And why wasn’t his bike stolen and where did he put his sandwiches??”.